In the long history of Korea, nothing compares to the 20th century division of the peninsula or the war that followed. That war has not finished, and a peace treaty remains elusive. China, North Korea and South Korea all seek a peace treaty, but 11 U.S. presidents since 1953 have been unwilling to agree.

If President Trump turns out to be the exception, that shift could help put an end to more than a half-century of conflict — and the role of the United States in determining whether peace arrives is not a small one. Neither is it coincidental: in fact, the U.S. has played a key role in keeping the conflict going as long as it has.

The division of Korea is not what Franklin Delano Roosevelt intended as World War II ended. As President, he had discussed with British Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden and Soviet leader Joseph Stalin an “international trusteeship” of Korea that would help bring the country out of Japanese colonial rule and restore its sovereignty. But Roosevelt died in April 1945 and President Truman had different priorities. The change of thinking by the Truman administration led to a change of direction that altered the course of history in northeast Asia.

In 1945, the Soviet army joined the Pacific war, and marched into Manchuria at the invitation of the United States. In the wake of that move, President Truman and Stalin agreed to divide Korea militarily, along a line of demarcation selected on Aug. 10, 1945, by two colonels in the Pentagon. The Korean people were not consulted. What started as a military partition in 1945 became a political division in 1948 when separate states were created in the north and the south — an invitation to conflict that made a war for the reunification of the peninsula inevitable. North Korea invaded the south in June 1950 but three months later, when US-led forces crossed the 38th parallel and threatened the Chinese border, Kim Il Sung’s war for reunification transformed into a global conflict in which China and the United States became the major players.

In July of 1951, armistice negotiations commenced. They continued for more than two years and consisted of 575 meetings. When the military commanders signed an armistice agreement on July 27, 1953, a ceasefire occurred. Hostilities ended more or less where they began. The armistice was predicated on the creation of a peace treaty and the withdrawal of foreign forces. The agreement was intended to be temporary and negotiations for a peace treaty were required to take place within three months.

Negotiations took place in Geneva in 1954 but no progress was made and no peace treaty eventuated. The U.S. Secretary of State, John Foster Dulles, would not negotiate and was not prepared to shake the hand of Chinese Foreign Minister Zhou Enlai. Zhou described Dulles’ attitude as obstructionist. Other representatives, including those from Britain and Belgium, were privately critical of the approach of the United States at the conference. At the conclusion of the conference, Dulles, who became TIME’s Man of the Year for 1954, refused to agree to a proposed joint statement reflecting a common desire to achieve the peaceful settlement of the Korean question.

A few years later, the prospect of a peace treaty was further diminished. In 1956, the Chairman of the U.S. Joint Chiefs announced that the Pentagon intended to introduce nuclear weapons into South Korea in contravention of clause 13 (d) of the armistice.

That clause prevented all parties from introducing new weapons or further troops onto the peninsula, other than as a like-for-like replacement. In 1957, despite the concerns of allies and the advice of the State Department, the United States announced its unilateral abrogation of clause 13(d) of the armistice. It said that North Korea had already breached the armistice, though no specific allegations were identified. From January 1958 on, the U.S. military brought “Honest John” nuclear missiles and atomic canons onto South Korean soil. The effect was to undermine the armistice. And the Neutral Nations Supervisory Commission, whose purpose was to ensure compliance with the armistice, largely lost its function. North Korea’s pretensions to develop its own nuclear arsenal date from this period.

After 65 years, there is still no peace treaty. Somewhat ironically, the nuclear status of North Korea has been one of the major sticking points.

Yet at the Singapore Summit with Kim Jong Un on June 12, President Trump revealed his aspiration to finally bring an end to the war. When asked if he touched on the issue of a peace treaty in his discussions with Kim, he answered “Of course,” and he ended his press conference by saying that he would also like to involve China and South Korea as signatories to a peace treaty.

There is much, including denuclearization, that must occur before peace can finally come. But when it does, it will conclude a sad and unresolved chapter of Korean history — one that Kim Dae Jung, former president of South Korea, has described as “a brief anomaly in 13 centuries of unified kingdom.”

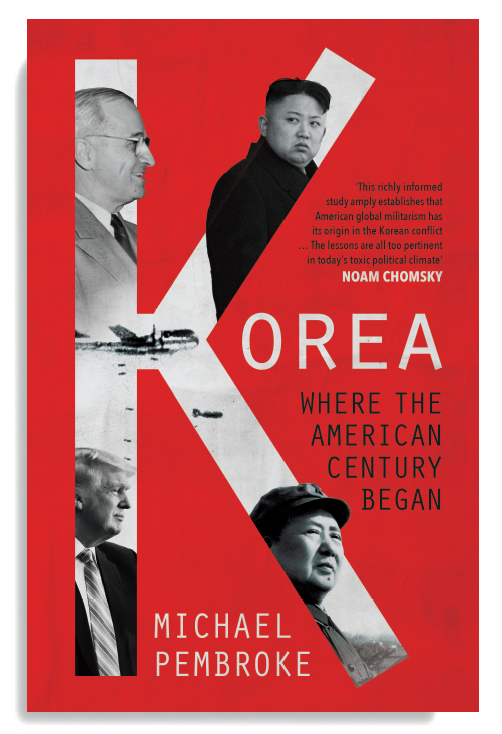

Michael Pembroke is the author of Korea: Where the American Century Began, published this month by Oneworld Publications.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Caitlin Clark Is TIME's 2024 Athlete of the Year

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com