We’ll never know precisely who discovered either chocolate or geometry. When it comes to putting them together, however, the titans of Big Candy have been squabbling over the rights to specific shapes for decades.

The shape wars were on prime display in July when Nestlé lost its latest appeal in the European Union to restore a trademark for the shape of the Kit Kat bar, which was successfully challenged by Mondelēz, a food-and-sweets conglomerate that sells a competing chocolate treat that is almost identical in its trapezoidal shape of the bars. (In three dimensions, this shape is known as a “pyramidal frustum” or, more generally, a “prismatoid.”)

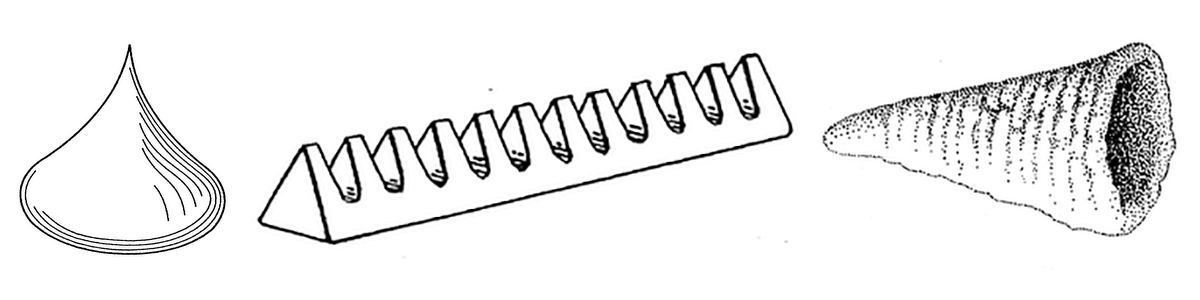

Candy and snack companies frequently attempt to develop a unique shape to distinguish their products from the competition, whether it’s the Hershey’s Kiss teardrop, the triangular prisms of the Toblerone bar — another Mondelēz product — or the conical ridged Bugle snack, better known among mathematicians as a “tractricoid.” All three have active trademarks with the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office:

A TIME examination of several thousand active trademarks identified several dozen shapes that were approved as trademarks, including the following examples:

But when is a shape just a shape, and when is it a calling card? “The government has a lot of discretion. The general rule is that the applicant must prove it has ‘acquired distinctiveness’ in the trademark before the shape can be registered,” says trademark expert Josh Gerben of the Gerben Law Firm. “The process of deciding if a shape has ‘acquired distinctiveness’ is incredibly subjective. It’s basically squarely up to one examiner to decide each case, and, the result could easily be different from one examiner to another.”

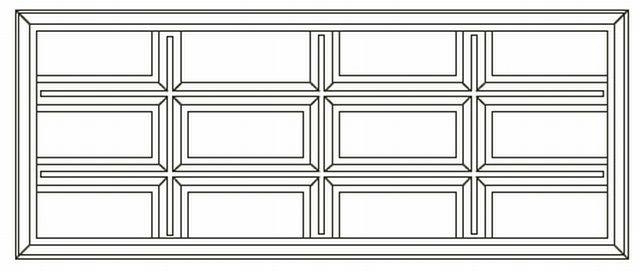

To Gerben’s point, the annuls of trademark applications are littered with failed attempts to register shapes that were, in the opinion of the examiner, either too generic or insufficiently distinct to the product — among a tangle of other technicalities that can sink a shape-based trademark application. This was on prime display when Hershey attempted to trademark the three-by-four rectangles in their classic candy bar:

While Hershey has dozens of active trademarks on its logo, their claim here was that the 12-bar segmentation of their product was also unique — a point on which the trademark office disagreed, citing the fact that, according to Supreme Court case law, the mere configuration of a product cannot be trademarked unless it is distinctive.

At issue was whether the twelve squares were merely functional — allowing consumers to conveniently break off pieces at a time, which would not qualify as “acquired distinctiveness” — or an intrinsic quality of the bar meant only to distinguish it from others. Hershey’s lawyers shot back “that applicant’s configuration is unique and stands apart from the numerous examples of shapes and sizes that are available to its competitors … It all depends on the person lucky enough to be eating them.”

(Meanwhile, Hershey’s website encourages chocolate bar enthusiasts to “Unwrap a bar, break off a square or two, savor and repeat.”)

Four years and hundreds of pages of evidence later, including an escalation to the trademark appeals board, Hershey was award the trademark on Apr. 23, 2013.

Generally speaking, companies have greater difficulty registering shapes than they do logos. “When you have these off-the-beat trademarks — you can also trademark a sound, or a color — one of the things the government is concerned about is awarding exclusive rights on a shape, sound or color that other companies might want or need to use,” Gerben said. And when a trademark for a shape is awarded, it does not universally apply to any product with that shape (or color, or sound), but only those in the same wheelhouse as the trademarked product such that some confusion could be possible.

To wit: Hershey would probably have a difficult time challenging Christmas ornaments that resembled its teardrop shape short of any evidence that the ornament was a deliberate attempt to fool customers into thinking it was a Hershey product.

Still, every country is different. An extensive search of trademark applications in the United States found no evidence that Nestlé has attempted to trademark the Kit Kat shape domestically.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Chris Wilson at chris.wilson@time.com