On Monday, Arthur Ashe Stadium in Queens, N.Y., swings open its doors to tennis fans, as the first round of the 2018 U.S. Open tournament begins. This year marks the 50th anniversary of the stadium’s namesake becoming the first African-American man to win a Grand Slam title.

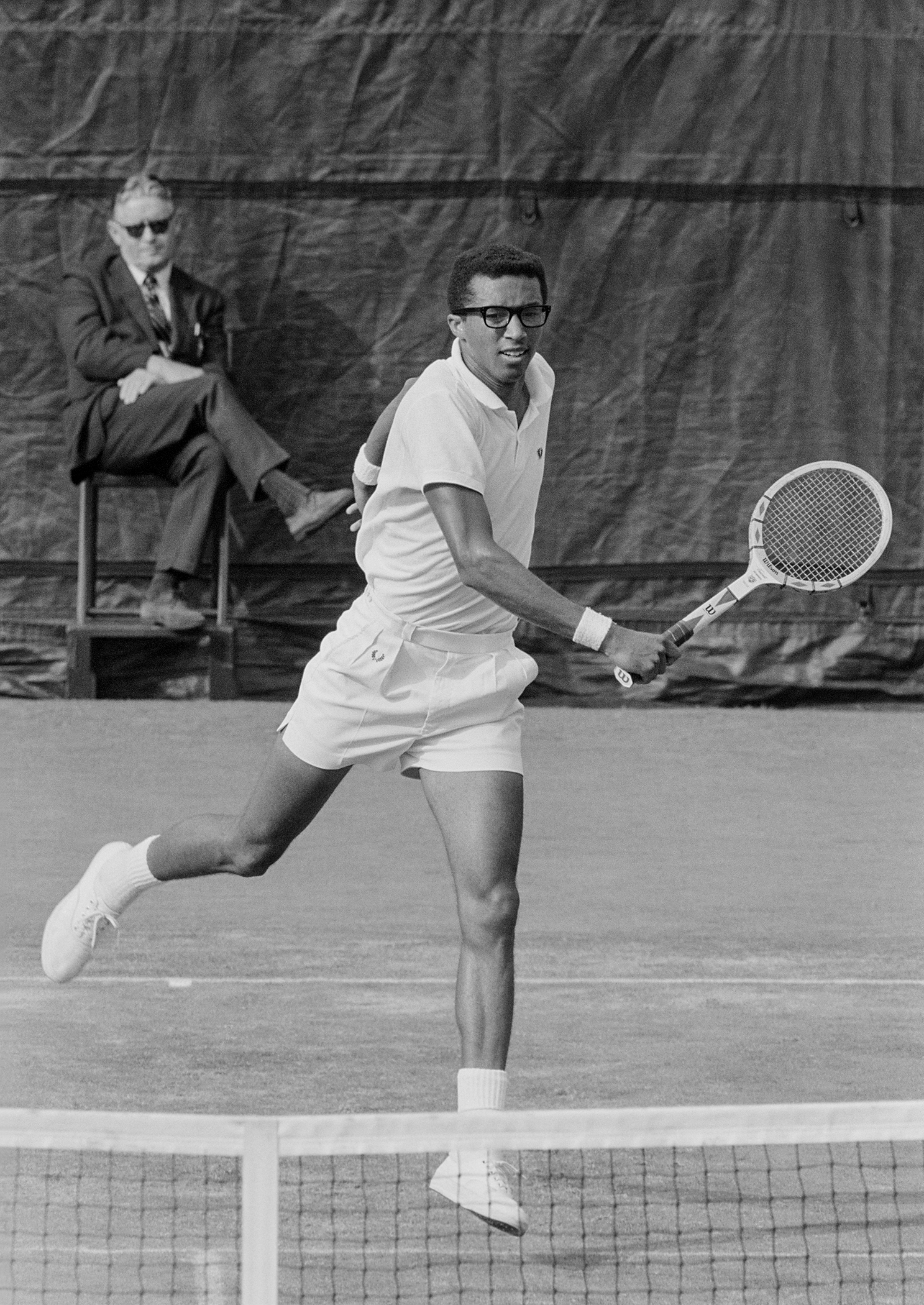

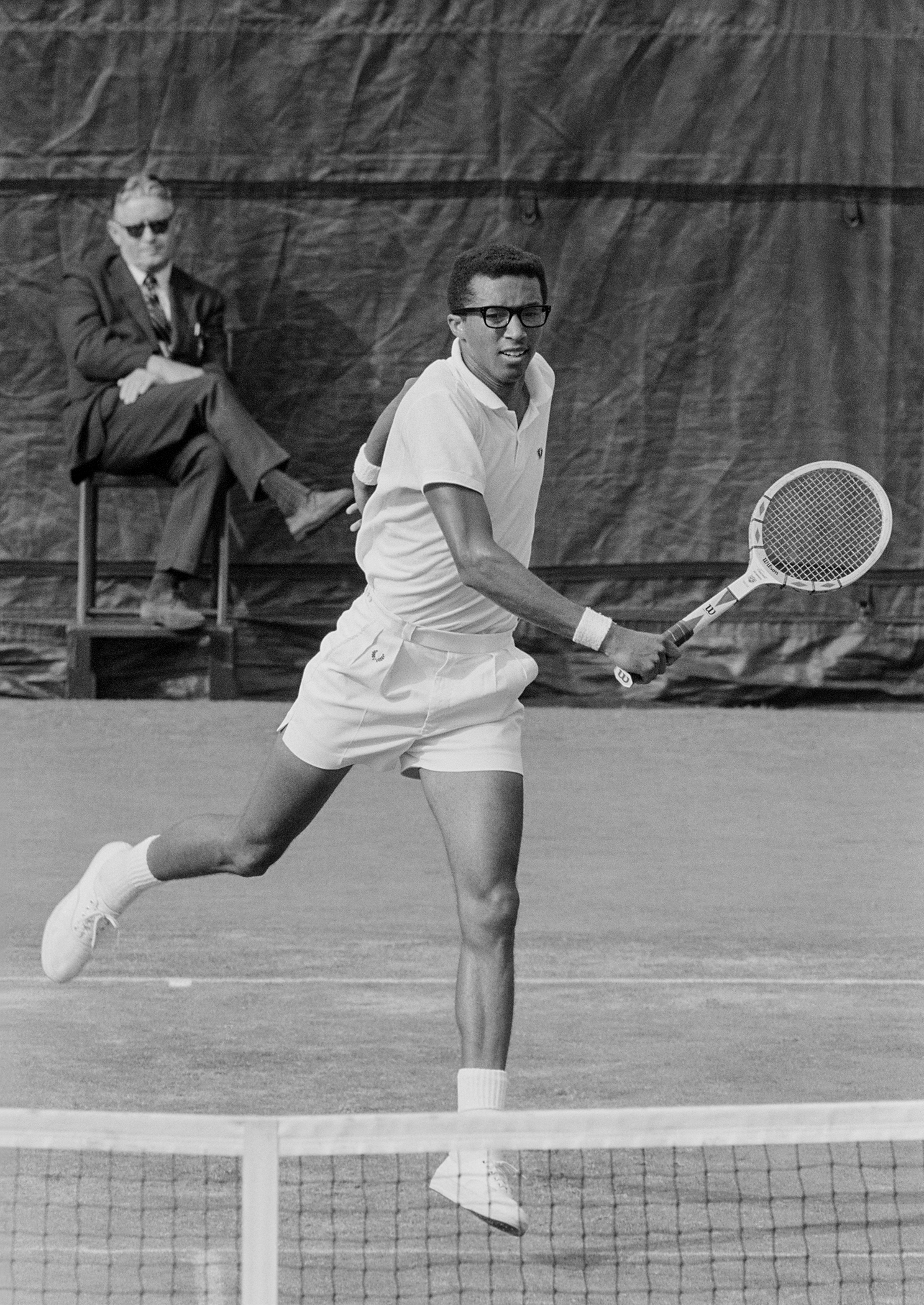

When Ashe defeated Tom Okker of the Netherlands on Sept. 9, 1968, it was an exciting game to watch, to say the least; the 25-year-old Richmond, Va., native served 26 aces throughout the match, 15 of them to win the first set, which went all the way up to 14-12. (Tiebreakers were introduced in 1970.)

Even so, the record $14,000 prize money for the match went to Okker, who was the last professional player standing that year; Ashe got a $20 per diem as an amateur. But things were changing for Ashe — by year’s end, he would be ranked the No. 1 tennis player by the United States Lawn Tennis Association — as well as for the world around him. Fifty years later, Ashe’s win stands out as not only a milestone in tennis history, but also a milestone in the civil rights movement.

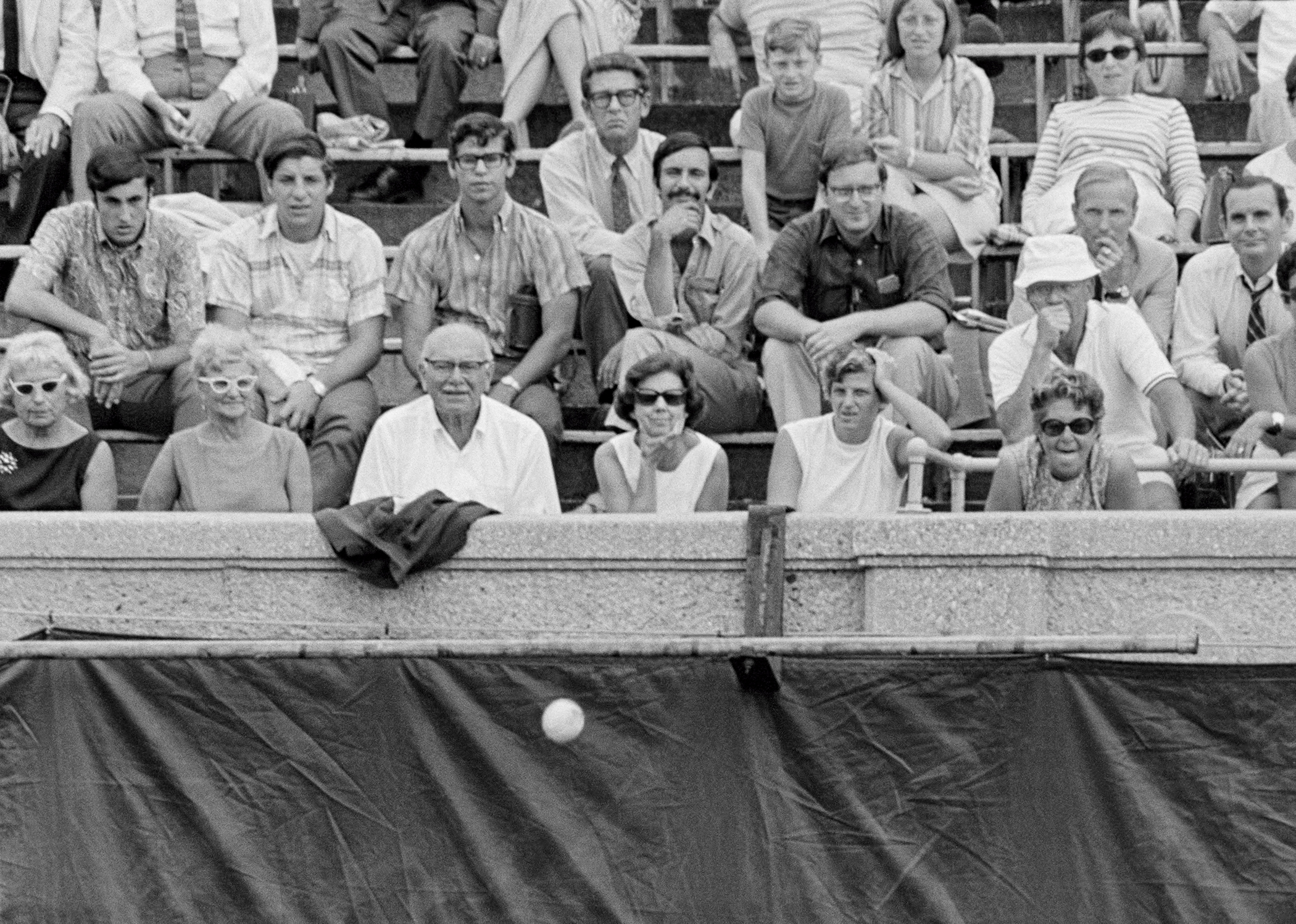

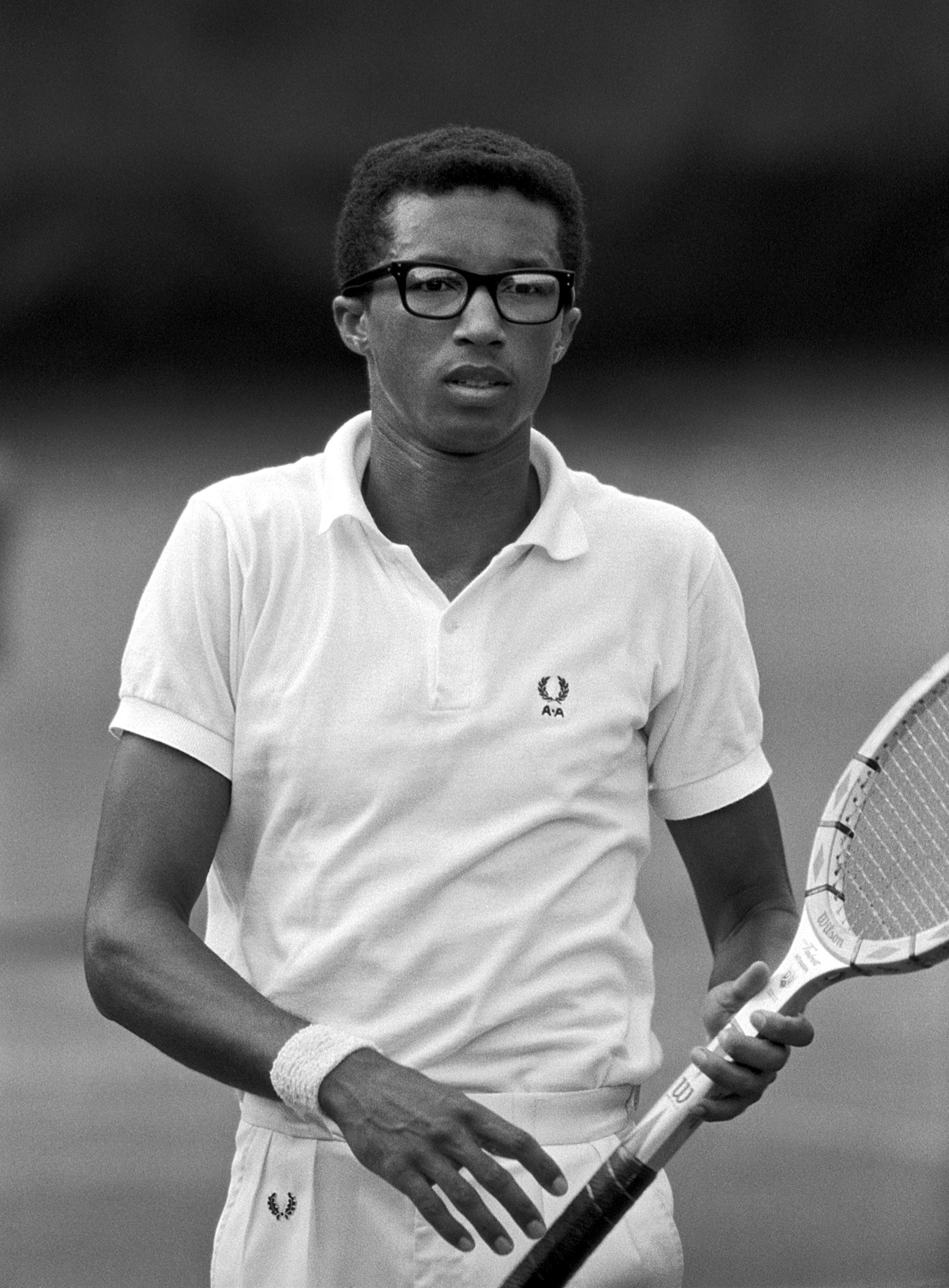

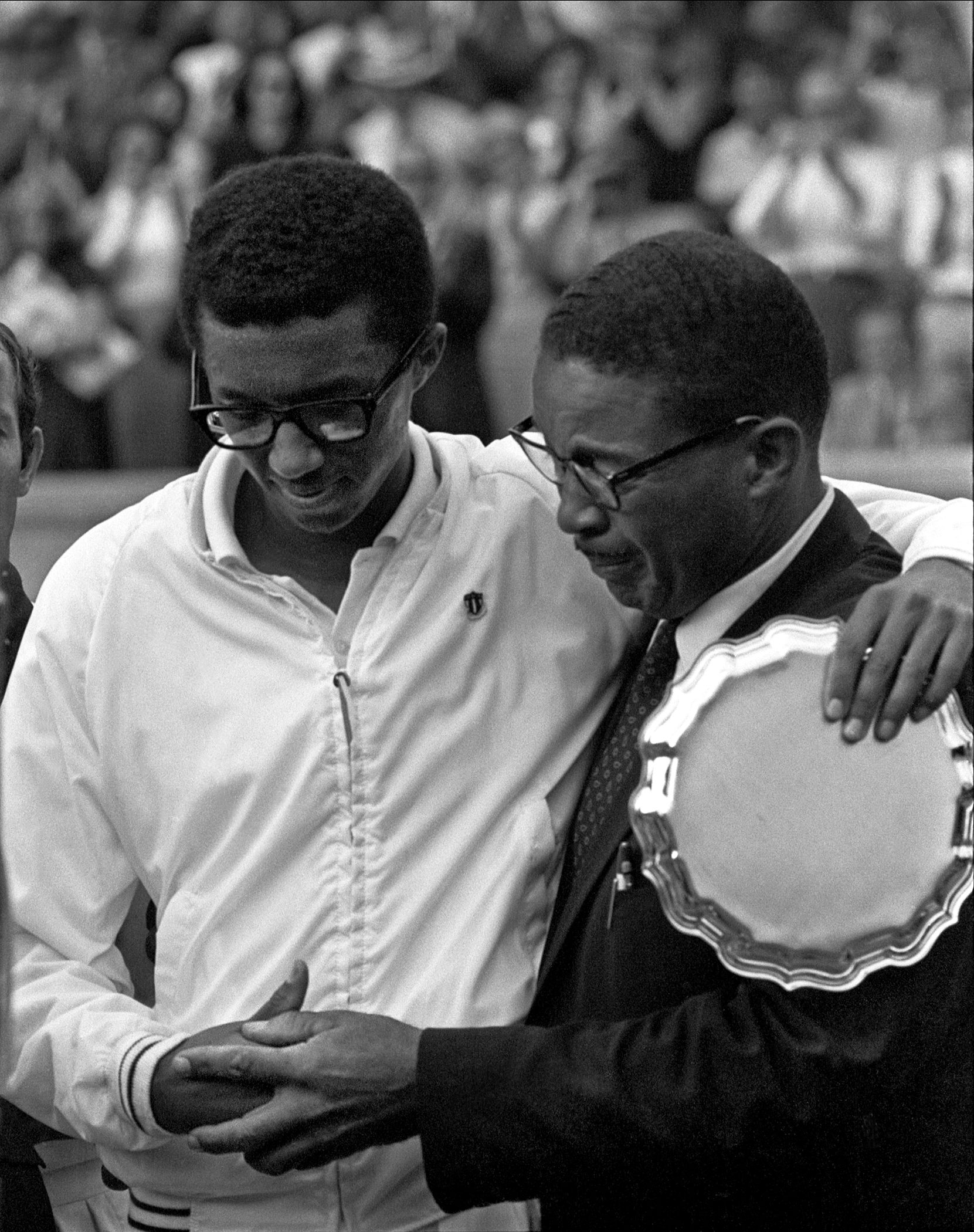

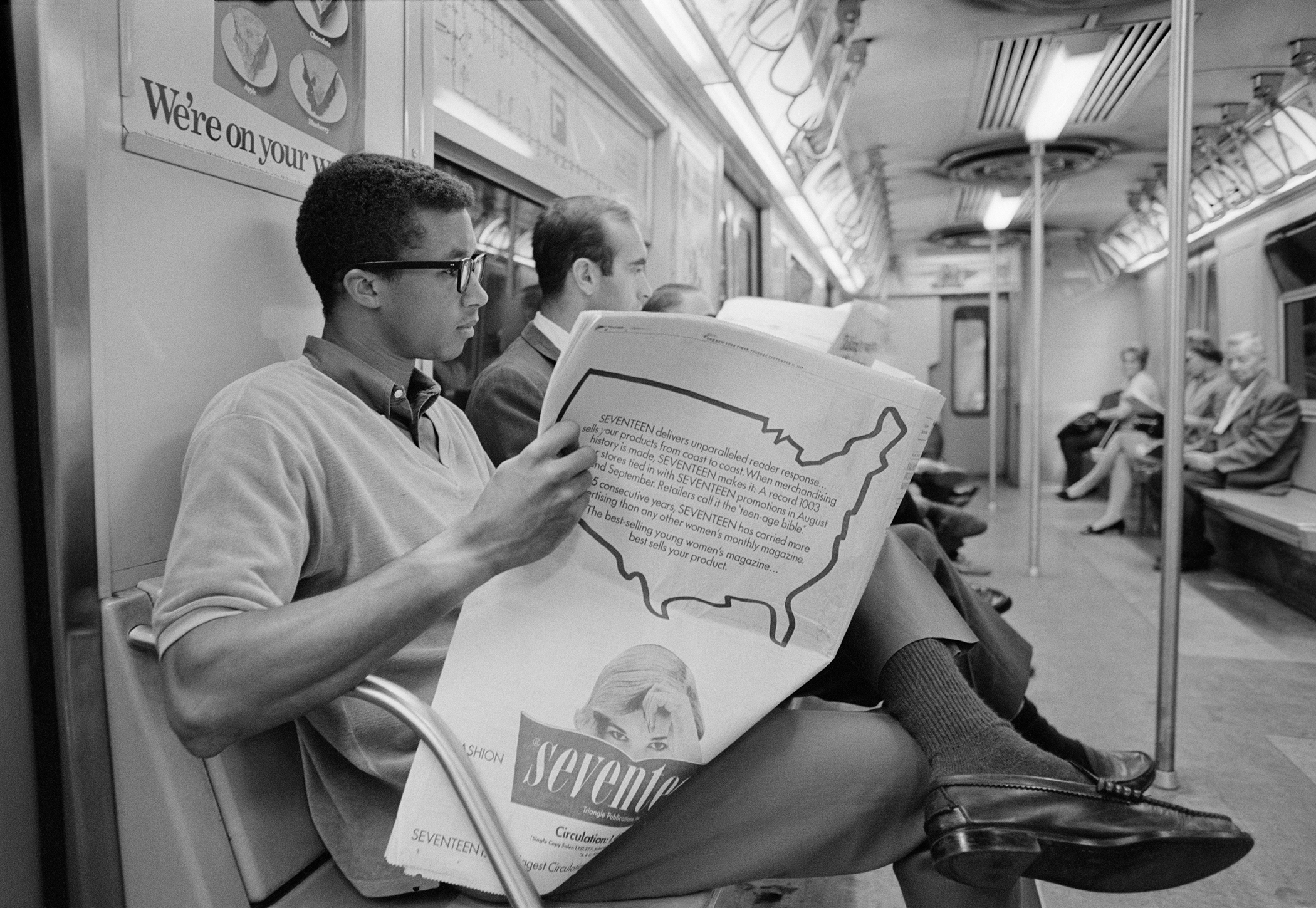

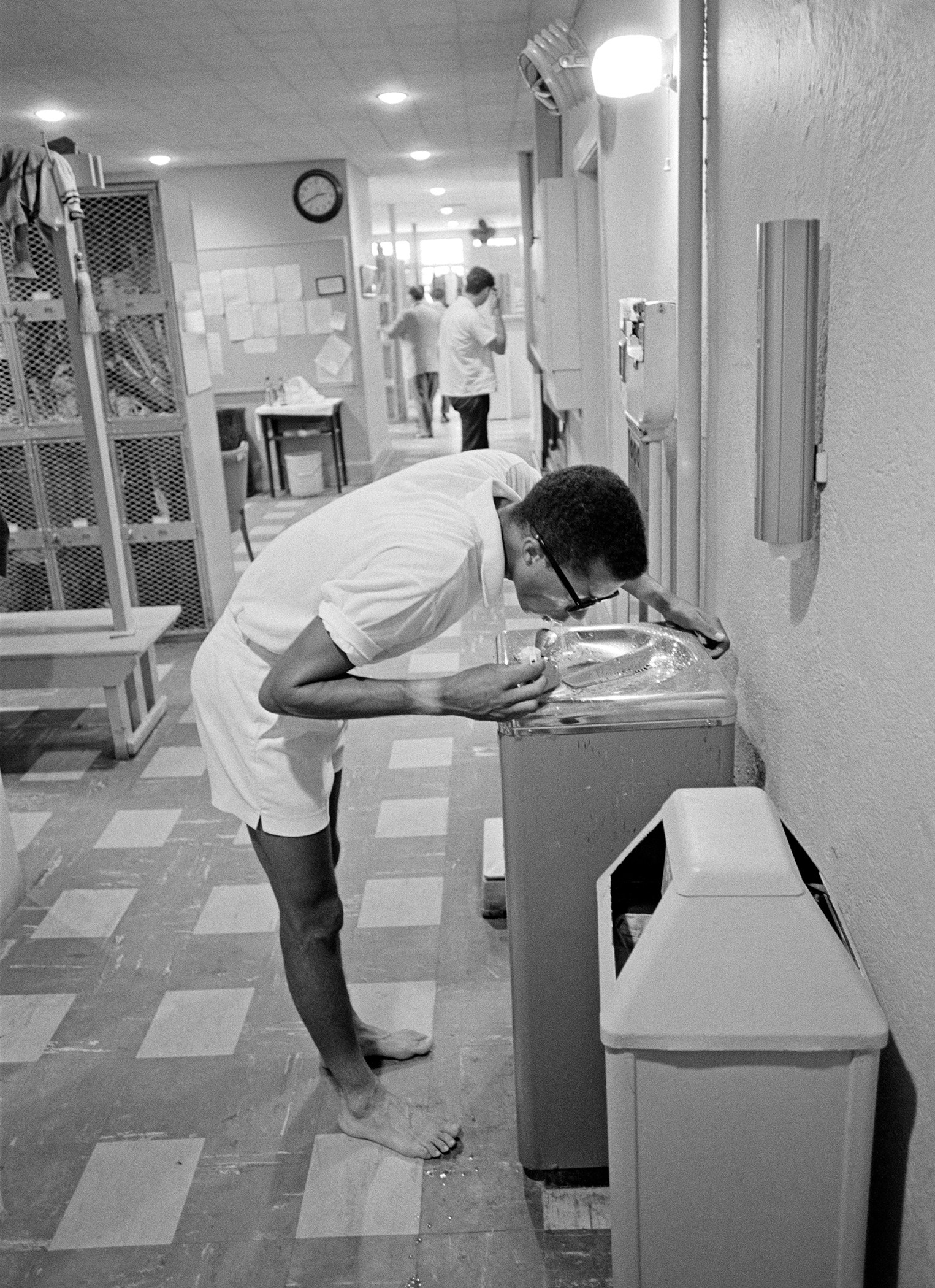

One of the many people watching tennis history be made that year was longtime TIME and LIFE photographer John G. Zimmerman, whose images from that day were included in LIFE’s cover story the following week, about Ashe’s achievement — but many of Zimmerman’s pictures were never published in the magazine. The new book Crossing the Line: Arthur Ashe at the 1968 U.S. Open, from which the images above are drawn, brings together those pictures 50 years later. The book includes hundreds that have never before been seen publicly, some of which are included in the gallery above.

Zimmerman shadowed Ashe during much of the 36 hours in before, during and after the U.S. Open that year. The pictures show the surprisingly ordinary events that led up to his extraordinary achievement, such as the solitary subway ride from his hotel in Midtown Manhattan to the match in Forest Hills.

The Sept. 20, 1968, cover of LIFE magazine would describe his style of keeping it cool on the court as “icy elegance.” But he didn’t hold back at all when it came to talking about the impact of his playing within the larger fight for racial equality.

“I can make my protest heard by winning,” he told LIFE. “People don’t listen to losers.”

And win he did. By the time Ashe died in 1993, after contracting HIV from a blood transfusion following heart bypass surgery, he had won 33 singles titles and 14 doubles titles. When he was posthumously awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom, President Bill Clinton remarked that Ashe had an “inner strength and outward dignity” that “marked his game every bit as much as that dazzling crosscourt backhand.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Olivia B. Waxman at olivia.waxman@time.com