In this floating city, water soaks every aspect of daily life–from our car-insurance premiums to our music to our fears of the future–but you can go weeks without seeing it. The Mississippi River slouches behind the wharves that line most of New Orleans’ 12-mile length. The oceanic expanse of Lake Pontchartrain is available to anyone who clambers over the levee, but most New Orleanians rarely make it up there. You see plenty of water in a storm, when the sewers jam and the streets become streams. But otherwise it is easiest, and most lovely, to visit the ancient bayou that is responsible for the city’s very existence.

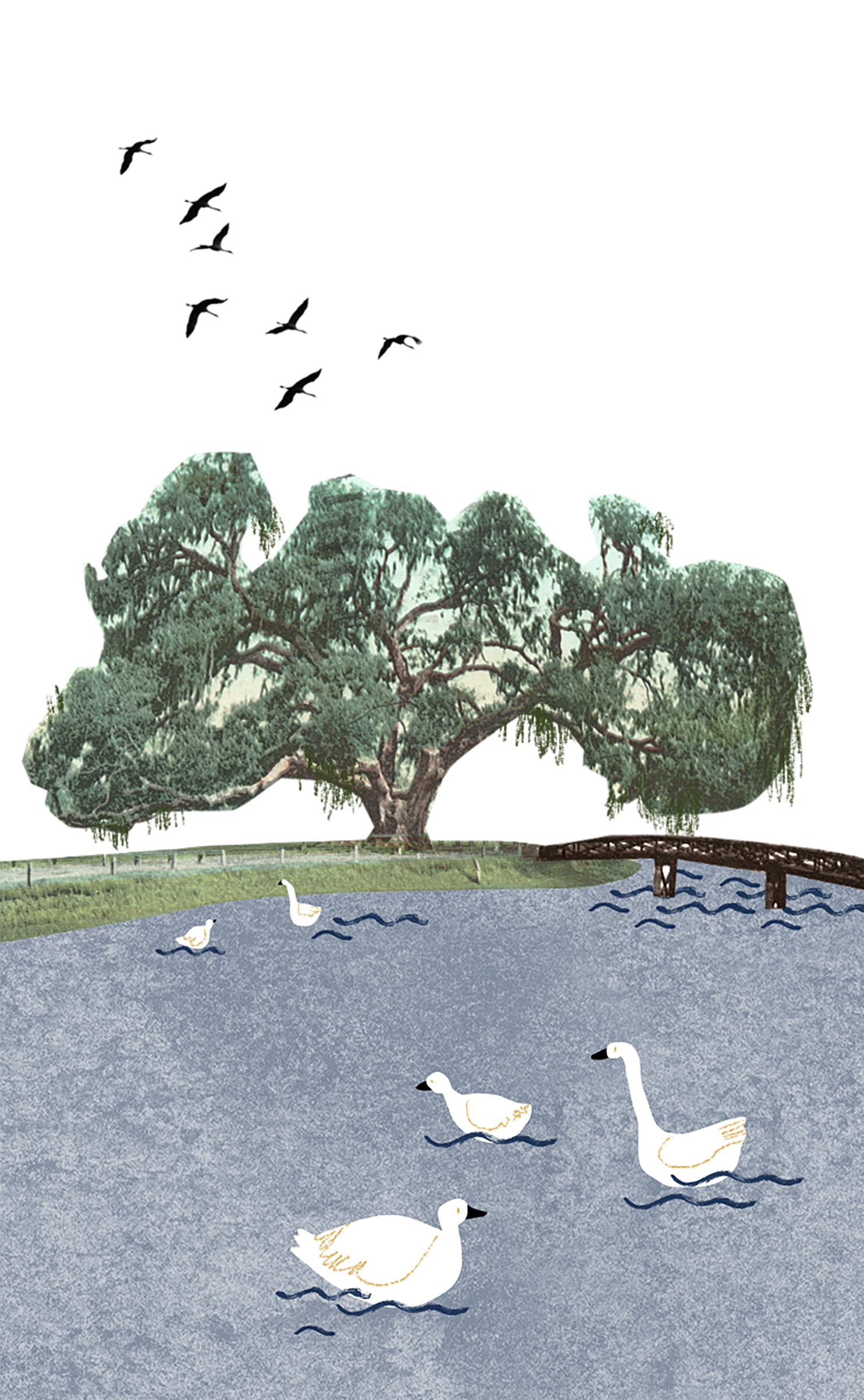

Not long ago, Bayou St. John was best known for being a good place to dump cars or bodies, and sometimes both together. But after years of civic cleanups and environmental restoration, it has been polished into an idealized emblem of a lost Louisianne landscape that never actually existed. It comes alive at dusk, particularly in the milder months when the air is sweet and still. Canoes, kayaks, handcrafted pirogues drearily float, observed by the older couples cradling wine in good crystal and the optimistic fishermen who seem rarely to have much success, and seem rarely to mind. Picnickers stake out the live oak by the Dumaine Street bridge or carry brown bags of crawfish to the low stone benches, built into the banks, that are only visible from the opposite side of the bayou. Or they lay towels on the splintered wooden slats of the Magnolia Bridge, built more than a century ago, designed to rotate on its center piling to allow boats to pass. A family of turtles lives beneath it. A little farther up, beneath the Esplanade Avenue bridge, lives an alligator.

The first French explorers to the area, in the early 18th century, wrote that alligators, mesmerized by cooking fires, would crawl out of the bayou to stare at the flames. The explorers squatted in an ancient village of huts thatched with palm fronds, built by the Acolapissa tribe in the 1600s. Two brothers, Bienville and Iberville, discovered the site after being approached, while traveling up the Mississippi River, by Indians offering to show them a shortcut between the river and the Gulf of Mexico. If you traveled around the toe of Louisiana’s boot to Lake Pontchartrain, you could follow Bayou St. John to a short portage trail that brought you to the river. The helpful Indians received, for their pains, a hatchet. Bienville and Iberville received New Orleans. The beginning of the portage trail became a settlement, which became the French Quarter.

Almost immediately the settlers prepared the Bayou for habitation, dredging and clearing and straightening. The process continued, with ever greater sophistication and cunning, until about five years ago, when the floodgates that block the bayou from the lake were opened for the first time in decades. As brackish water rushed in, speckled trout, redfish and largemouth bass gradually returned, trailed by herons, ibises, terns, waxwings and parakeets. The reunion of the bayou and lake reflects the city’s new way of thinking about its place in the swamp. After three centuries of doing everything to keep water out–building levees, paving over canals, pumping and diverting–New Orleans has decided to learn to live with it. We have no choice. It’s our future.

But in New Orleans the past counts more. It has always been a city of transplants but the only way to be a true New Orleanian is to be born here. After nearly a decade, I’m a transplant; a decade from now, I’ll still be one. My 2-year-old son is a native. After momma and dada, his first words were tuba, drums and turtle. His first canoe trip, first alligator sighting and the first time he quacked at a duck, came on Bayou St. John. On a recent trip to visit grandparents in New York City, we walked to the Hudson River. At the first glance of its broad brindled trunk, about 40 times the width of our local tributary, he yelled, to the wonder, and alarm, of his grandparents: Bayou!

Rich’s latest novel is King Zeno

This story is part of TIME’s August 6 special issue on the American South. Discover more from the issue here.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com