Nearly every morning in Gainesville, Fla., I tie on my sneakers and go for a run through my quiet neighborhood to the Hawthorne bike trail, then into Paynes Prairie for a wake-up jolt of beauty.

Early in the morning, the light catches the fog rising up from the ground and the moisture hanging on the tips of the grasses, highlighting it all in gold. Clumps of damp Spanish moss hanging from branches above my head shine like dimmed lanterns. A fox or a deer trots across my path and vanishes into the pines and palmettos; a rat snake, a single shining muscle, lies in the sun and blocks my way; strange birds whir in the air above my head. I never go more than a few miles from the busy downtown or University of Florida, but as I run I feel as though I’ve been transported in time hundreds of years to a pre-automobile, pre-air-conditioned Florida, a place of infinite strangeness and menace and possibility.

It can seem odd to imagine that there could be a prairie in Florida, which many people assume to be a state mostly made of beaches and swamps and orange groves and condominium complexes. But a prairie there is, which the great Quaker naturalist William Bartram visited and marveled at in 1774, writing, “Now on a sudden opens to view an inchanting scene, the great Allatchua Savannah. Behold, a vast Plain of water in the middle of a Pine forest 15 Miles in extent & near 50 Miles in circumferance, verged with green level meadows, in the summer season, beautifully adorned with jeting points & Prometoryes of high land.” Bartram visited a Seminole village at Cuscowilla–now Micanopy–and was given the derisive nickname Puc-Puggy, or Flower Hunter, for his habit of preserving and drawing botanical specimens. Most historical accounts agree that the prairie was later named after a Seminole chief called King Payne who was killed in 1812 in a skirmish with colonizing European Americans.

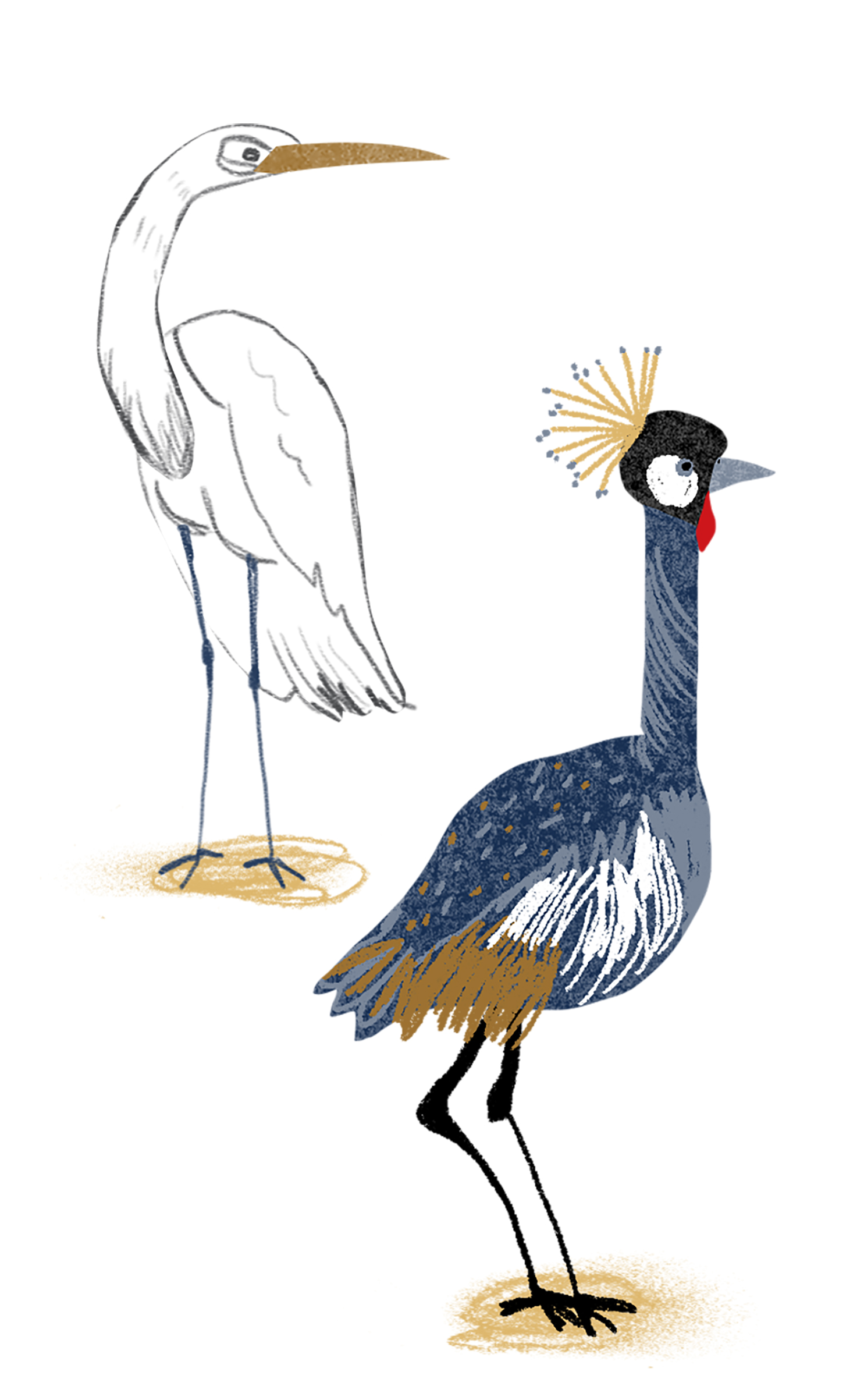

These days, Paynes Prairie covers more than 21,000 acres of Florida savanna, dotted here and there with forested rises called oak hammocks. It is shot through with canals and even a body of water called the River Styx, which feels appropriately dark and mystical. The Alachua Sink is a giant basin of limestone that drains the overflow of water collected by the savanna into an underground river, sending it miles in the dark before pumping it into the Santa Fe River. There’s a visitor center at the Alachua Sink with a beautiful wooden boardwalk where you can walk out into the prairie itself and catch a glimpse of the alligators sunning themselves on the banks of the canals. When the water is low, the gators seem terrifyingly thick and rubbery and unnaturally still, as though they’re mimicking blown semi tires on the side of the highway. Once in a while, you’ll see two alligators fight, or a single, hungry one creep slowly toward one of the long-legged birds–cranes, ibises, egrets or herons–that wade in the shallows. If you’re lucky, you will see one of the bison that wander the prairie; even luckier and you’ll see the wild horses that are the descendants of the caballos brought by the Spanish, the first Westerners to colonize Florida. All the while, as you stand there looking across the flat expanse, the air is thick with the calls of thousands of birds flying and fishing and nesting in this great, green, humid roil of irrepressible life.

For the first five years that I lived in Florida, my morning run saved me from despair. We live in Gainesville because my husband took over a family business, which in some ways is a gilded cage: lovely and secure, but a decision you can’t ever back out of. For far too long, I felt trapped in a place that was alien to my sensibilities, a place that had never been of my choosing. But over time, the run in Paynes Prairie led me to pay ever closer attention to the natural world around me, to mark the subtle changes from day to day, the more operatic and ravishing ones from season to season. Because I am a novelist, one thing I know very well is that close, sustained, careful, daily attention is a profound form of love. I pay close daily attention to Paynes Prairie–it is the very best of the wild, teeming state that I adore–and it has become the place in Florida I love most of all.

Groff’s latest book is Florida

This story is part of TIME’s August 6 special issue on the American South. Discover more from the issue here.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com