On Friday, North Korea is set to hand over a set of presumed remains of prisoners of war and those missing in action during the Korean War, after Kim Jong Un and Donald Trump signed a statement promising the “immediate repatriation of those already identified” during their summit in Singapore in June.

The ceremony is deliberately taking place on the 65th anniversary of the signing of the armistice that ended the roughly three years of fighting between 1950 and 1953. It was signed by U.S. Army Lt. Gen. William K. Harrison Jr. of the United Nations Command Delegation and North Korean General Nam Il, who also served as China’s representative, at Panmunjom in the Demilitarized Zone bordering North Korea and South Korea. The armistice put a halt to outright hostilities between the two sides, but the Associated Press reports that, more than half a century later, 7,699 U.S. service members are still missing from the Korean War.

In a recent online essay, Mark Fitzpatrick, who heads up the non-proliferation and nuclear policy program at the International Institute for Strategic Studies, wrote that “North Korea treats the remains issue as bait to obtain political objectives.” And, though efforts to repatriate such remains have been going on for decades, identification and recovery of the remains of those Americans who never came home from the war remains an ongoing project.

Contributing to the difficulty is the fact that the armistice signed in 1953 was a ceasefire, but not a permanent peace treaty. The people who signed it were well aware of the future conflict that might cause, but willing to take what they could get at the time.

The week after the signing, TIME described the feeling of unfinished business in the room:

Truce came to Korea in a stark, deliberately underplayed ceremony.

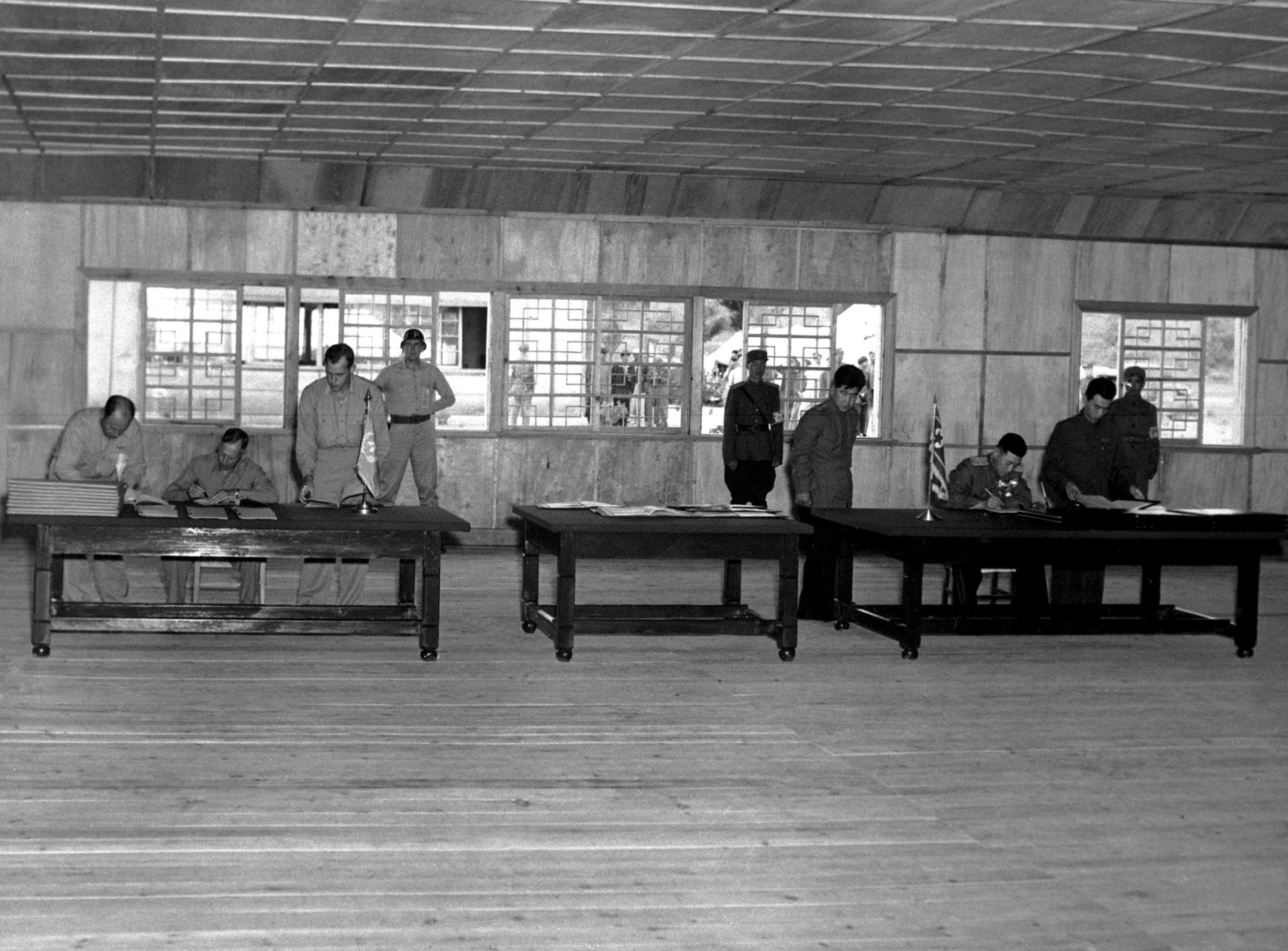

At Panmunjom, shortly before 10 a.m. (the hour fixed for the signing), nervous little Communist sentries in baggy pants and wilting red epaulettes scurried about, brushing off the board walk where their masters were to tread. The bleak, new truce building, hastily and especially erected by the Reds, smelled of fresh pine. Outside, it still showed the marks of two big Picasso-style peace doves, put up by the Reds, taken down at Mark Clark’s demand. Inside it was stifling hot. Sweating U.N. observers and correspondents, including officers from each national contingent, filed in and sat on metal chairs at one side of the hall; the Communist group sat at the other side. U.N. and Communist guards stood motionless around the walls. There were three large tables, one for documents, a second bearing a U.N. flag on a brass stand, the third with a North Korean flag similarly mounted.

Promptly at 10, the two chief actors entered. Lieut. General William K. Harrison, the U.N. senior delegate, tieless and without decorations, sat down at a table, methodically began to sign for the U.N. with his own ten-year-old fountain pen. North Korea’s starchy little Nam II, sweating profusely in his heavy tunic, his chest displaying a row of gold medals the size of tangerines, took his seat at the other table, signing for the enemy. Each man signed 18 copies of the main truce documents (six each in English, Korean, Chinese), which aides carried back & forth. The rumble of artillery still rolled through the building. Flashbulbs blazed and cameras whirred as the two chief delegates silently wrote. When they had finished, West Pointer Harrison and Nam II, schoolteacher in uniform, rose and departed without a word to each other, or even a nod or a handshake.

Without Fireworks. Outside, a correspondent asked a British officer whether the Commonwealth Division would celebrate with the traditional fireworks. “No,” said the Briton, “there is nothing to celebrate. Both sides have lost.”

Thus, 37 months and two days after the Russian-trained North Koreans attacked across the 38th parallel, the Korean war—a devastating struggle, laced from the start with glory, agony, triumph, frustration—came to a halt, perhaps temporary, perhaps permanent. The war had cost the U.S. more than 140,000 casualties (some 25,000 dead, 102,000 wounded, 13,000 missing and captured), $22 billion. The problem of ending it had roweled the best brains of two U.S. Administrations, and had helped to win a national election for one, to lose it for the other.

The two parties expected to draw up a more permanent peace treaty at the Geneva conference the following year, but they came to an impasse.

Read more here on why North Korea and South Korea are technically still at war

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How Donald Trump Won

- The Best Inventions of 2024

- Why Sleep Is the Key to Living Longer

- Robert Zemeckis Just Wants to Move You

- How to Break 8 Toxic Communication Habits

- Nicola Coughlan Bet on Herself—And Won

- Why Vinegar Is So Good for You

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Write to Olivia B. Waxman at olivia.waxman@time.com