Researchers have long touted the mood-boosting effects of green space and spending time outdoors — and a new study emphasizes just how much of an impact your environment can have on your mental health.

The paper, published Friday in JAMA Network Open, found an association between urban restoration efforts in Philadelphia and the mental health of city residents. “Cleaning and greening” urban lots in Philadelphia was linked to a drop in neighborhood residents feeling depressed or worthless, and a slight uptick in overall resident mental health, the study says.

“Vacant lot greening is a very simple structural intervention that’s relatively low-cost and that can have a potentially wide or broad population impact,” says study co-author Dr. Eugenia South, an assistant professor of emergency medicine at the University of Pennsylvania’s Perelman School of Medicine. “Performing simple interventions to the neighborhood environment has an impact on health.”

For the study, a team of researchers identified 541 vacant lots in Philadelphia and divided them into clusters: groups of lots within a quarter-mile radius that all showed signs of urban blight, like illegal dumping, abandoned cars and overgrown vegetation. Next, they interviewed 442 adults living within one of these clusters. People were told they had been chosen for a study focused on “improving our understanding of urban health,” and answered questions about mental health. They did not know the researchers were involved in forthcoming urban greening efforts.

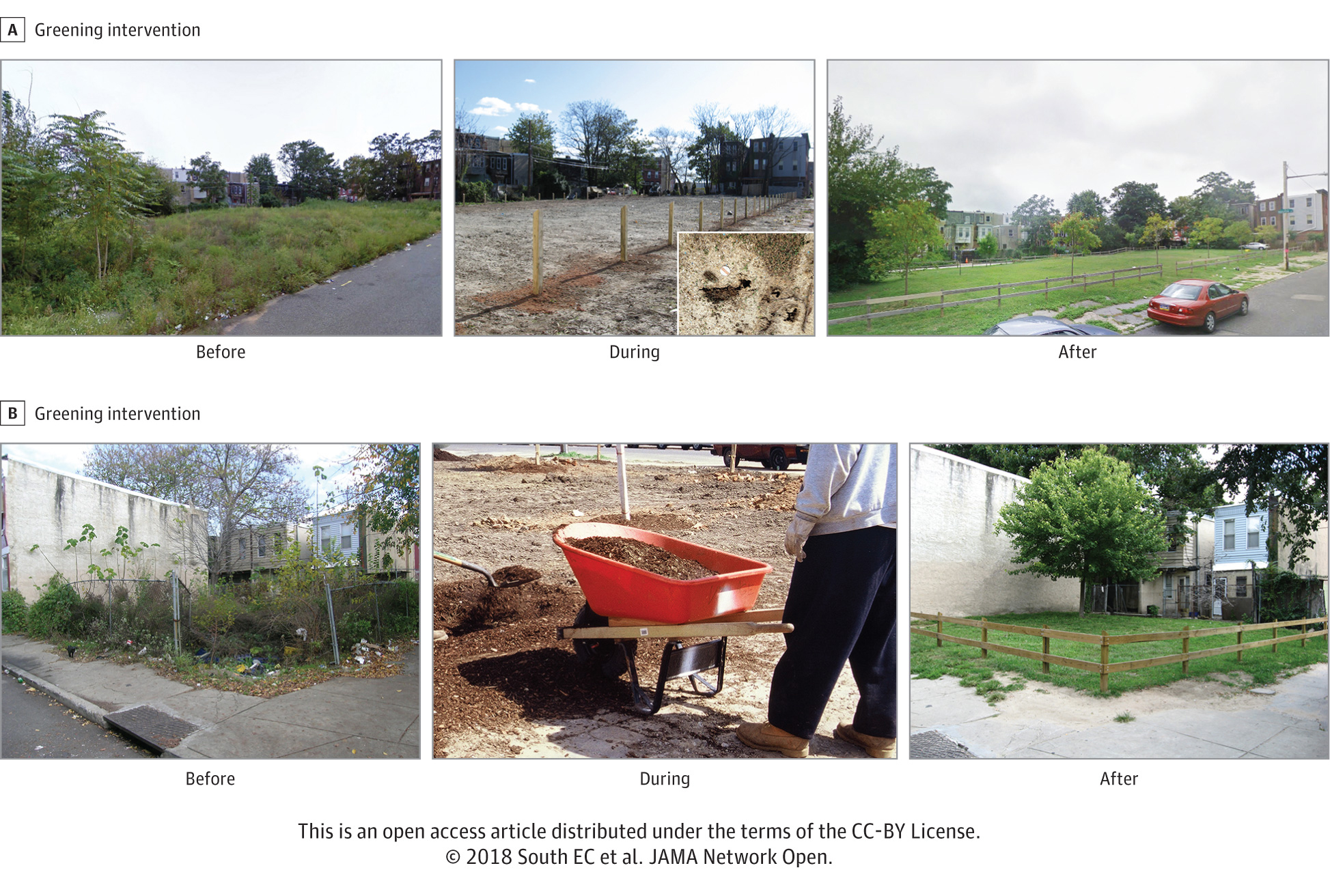

After the initial surveys were completed, the researchers randomly selected 37 lot clusters for a greening intervention that involved removing trash and debris, planting grass and trees, installing a fence and performing routine maintenance. Another 36 clusters had trash removed and minor maintenance, but little in the way of increasing green space. The final 37 were left untouched.

Within 18 months of completing the restoration efforts, the researchers re-interviewed 342 of the original study participants, about a third of whom lived near one of the clusters assigned to the greening intervention. Compared to people who lived near lots with no improvements, these people experienced a 41% drop in depressive feelings and an almost 51% drop in feelings of worthlessness. Overall improvements to mental health didn’t quite reach statistical significance, but South says the researchers are “pretty confident that people are experiencing better mental health.”

The study’s results suggest that there’s something special about green space, as people living near a lot cluster that only went through trash removal did not see significant mental health benefits.

“The green space in and of itself is important,” South says. “There are several mechanisms through which that’s proposed to happen, including increased social connections and recovery from mental fatigue and coping with general life stress. The fact that it’s green space, and not, say, a parking lot, is important. The wooden fence also matters: That fence kind of delineates the space as a space that is now being cared for — it’s a space that people are paying attention to.”

MORE: Why Hiking Is The Perfect Mind-Body Workout

Greening was particularly impactful for people living in neighborhoods falling below the poverty line. “The poorer neighborhoods are the most hard-hit, as far as the neighborhood environment being dilapidated and run down,” South says. “Those people are potentially the people who have the biggest health impact from the neighborhood environment, so making changes to this environment could have the biggest impact on them.”

Taken together, the results suggest that urban greening could offer a real opportunity for cities looking to improve population mental health, especially since it only cost about $1,600 to transform an abandoned lot, and $180 per year to maintain it, South says. She and her colleagues are already working with the Pennsylvania Horticultural Society to implement the program more widely in Philadelphia and says other cities have also expressed interest.

“This is not an end-all and be-all treatment for depression in any way — this goes along with other individual patient treatments — but when you think about the amount of money [spent on mental health care], it’s a pretty low-cost intervention,” South says.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Introducing the 2024 TIME100 Next

- The Reinvention of J.D. Vance

- How to Survive Election Season Without Losing Your Mind

- Welcome to the Golden Age of Scams

- Did the Pandemic Break Our Brains?

- The Many Lives of Jack Antonoff

- 33 True Crime Documentaries That Shaped the Genre

- Why Gut Health Issues Are More Common in Women

Write to Jamie Ducharme at jamie.ducharme@time.com