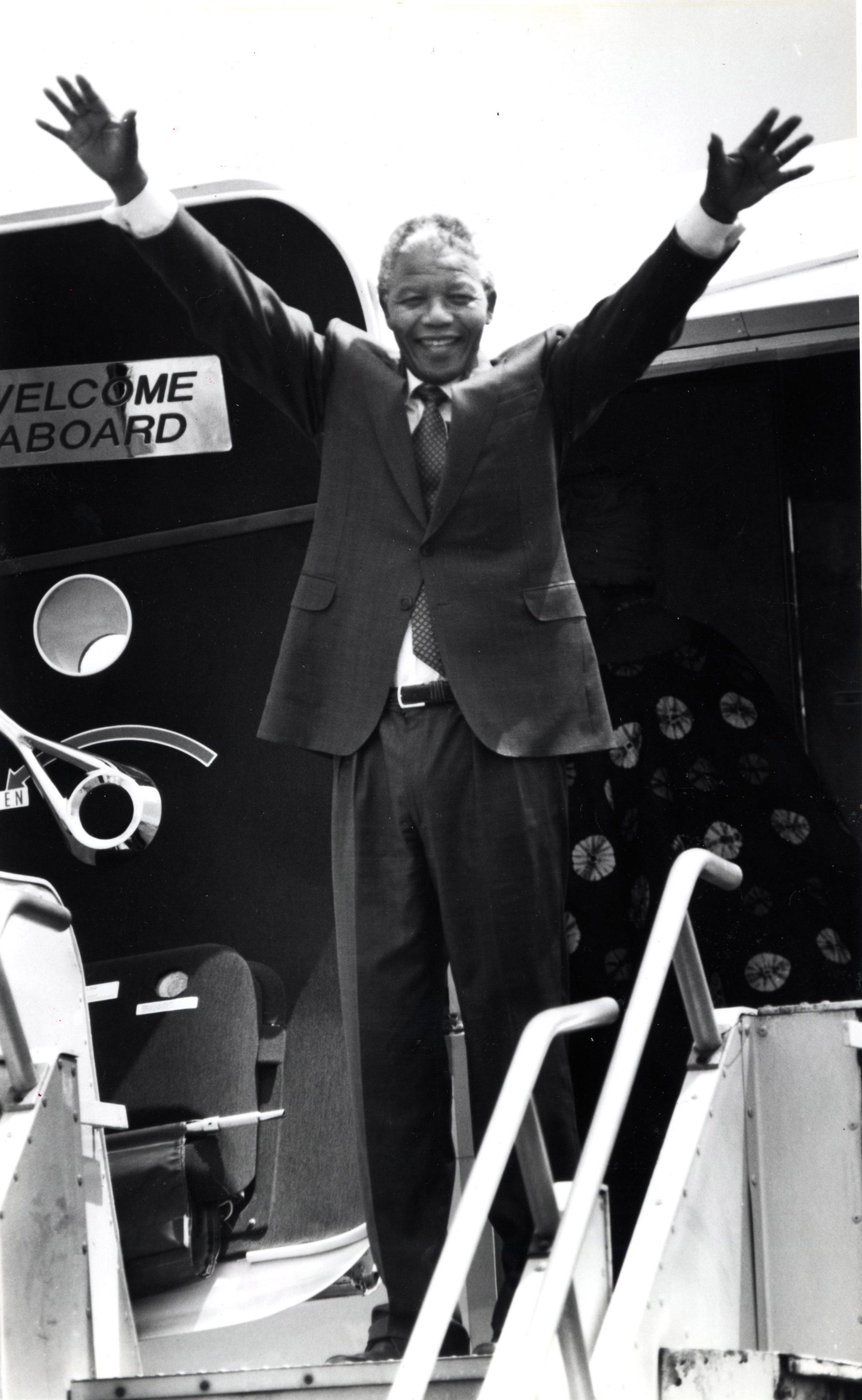

A full 100 years after Nelson Mandela’s July 18, 1918, birth, he is remembered around the world as a symbol of peace and freedom, for ushering South Africa into a democratic, post-apartheid future.

Yet throughout his life, Mandela had a habit of saying that he was “not a saint,” as TIME noted in his 2013 obituary. Perhaps more surprisingly from today’s perspective, many people around the world felt the same way. In fact, Mandela remained on U.S. terrorist watch lists until 2008.

Understanding the reasons behind that fact requires seeing Mandela’s life and work in the context of both the history of the African National Congress (ANC), the political party with which Mandela was associated, and the history of United States attitudes during the Cold War.

More from TIME

On the ANC side, a deciding factor was a shift in strategy that led some activists to see violence as a possible means to an end; the end being, the end of South Africa’s official government policy of the separation of blacks and whites. Since its founding in 1912, “the ANC fought against apartheid for decades through rigorously nonviolent means, mostly labor strikes and public service boycotts,” TIME later reported. But, “The ANC’s policy of nonviolence received a sudden and brutal setback in 1960.”

That’s when the Sharpeville Massacre took place. In 1960, South African police killed 69 black protesters in the town 40 miles south of Johannesburg; amid the crackdown that followed, the government banned the ANC. As the ANC went underground, Mandela became the head of the military wing of the African National Congress, Umkhonto we Sizwe (Spear of the Nation), also known as MK. In 1964, he was convicted of sabotage and treason, and wound up imprisoned until 1990. TIME later described the group’s activities from 1962 as “low-level guerrilla war.”

Defending the shift in strategy as a last resort, Mandela said in one of his interviews from prison, “‘The armed struggle [with the authorities] was forced on us by the government.'”

At the same time — even as some American activists embraced or aided the South African fight for racial justice — the U.S. government was deep in the Cold War. As Mandela was sent to prison, his fellow ANC leader Oliver Tambo avoided that fate, TIME later reported, “because he had been sent abroad to open a headquarters and search for funds” for keeping the campaign going underground. “The newly exiled revolutionary found some interest in his cause in Scandinavia but little in other Western nations. Tambo’s pleas were better rewarded by the Soviet Union, which beginning in 1963 became increasingly important to the ANC as a supplier of funds, military equipment and scholarships for young members. Precisely how much influence Moscow has over A.N.C. policies and personnel is a matter of deep controversy.”

However much influence it was, it was enough to get on the wrong side of the United States, between Mandela and his disciples getting funding from the Communists and their willingness to engage in violence. Mandela was viewed as “a person on the wrong side of the Cold War,” as historian Robert Trent Vinson, author of The Americans Are Coming!: Dreams of African American Liberation in Segregationist South Africa, puts it.

Even decades later, as Americans became increasingly attuned to the injustice being perpetrated in South Africa, the influence of the Cold War was felt in the dynamic between the U.S. and that nation. “When Congress finally passed new U.S. economic sanctions against South Africa three weeks ago, it ordered President Ronald Reagan to issue a report early next year detailing any Communist influences on the ANC,” TIME put it in 1986. “The Administration is understandably troubled that some members of the African National Congress are Communists, but to alienate those who are not is to risk enlarging the Communist ranks.”

In a 1986 speech, President Reagan also warned of “calculated terror by elements of the African National Congress,” including “the mining of roads, the bombings of public places, designed to bring about further repression, the imposition of martial law, and eventually creating the conditions for racial war.” The Department of Defense included the ANC in a 1988 report billed as profiles of “key regional terrorist groups” from around the world. Indeed, ANC actions during this period would include nighttime raids that destroyed fuel storage tanks and nearly two days of fires in 1980, a bombing at a bar in Durban that left three dead and more than 60 wounded, and a car bomb that killed 19 outside of the headquarters of the country’s Air Force in Pretoria in 1983. The later ANC apologized for civilian deaths that occurred as a result of “insufficient training.”

Meanwhile, Mandela was in prison. But, removed from the fight on the ground, Mandela ended up having a massive impact on the fight for anti-apartheid justice in South Africa — and, especially as anti-apartheid sentiments spread around the world, global opinion of him shifted dramatically.

“He comes out of jail an old man, much more ready to compromise after almost 30 years in jail,” argues Peniel Joseph, Founding Director Center for the Study of Race and Democracy at the University of Texas at Austin. “When he comes out, he’s saying we’re renouncing violence.”

TIME explained the specific events that led to the transformation in the perception of Mandela in its issue naming Mandela and South African President F.W. De Klerk Men of the Year for 1993:

Several interesting changes occurred during Mandela’s long, long incarceration. For one thing, his enforced isolation slowly transformed him into a mythic figure. Incommunicado, without the opportunity to speak out on specific issues, Mandela in his silence became South Africa’s most persuasive presence: an inspiration to blacks, a recrimination to whites. What is more, he sensed the moral power his confinement had conferred. Mandela had always been willing to talk; violence was his recourse when the other side would not listen. One day in 1986 he sat down and wrote a letter to the government proposing a dialogue on the nation’s future. This gesture received a secret but surprisingly willing response from President P.W. Botha, a hard-liner on apartheid who nonetheless had begun to sense his country’s escalating dilemma. Apartheid was collapsing of its own inherent absurdity. Moreover, the outlawed A.N.C.’s 1984 call to make South Africa “ungovernable” had been answered by a surge of black demonstrations and acts of civil disobedience. To put down such unrest, the government had to use increasingly brutal police and military actions, many of them filmed by news cameras and televised to appalled viewers around the globe. These ugly spectacles increased international pressure for economic sanctions against South Africa. Whites saw their nation becoming an international pariah. Realizing he needed Mandela, Botha arranged a meeting with him at the presidential residence, Tuynhuys, in Cape Town in July 1989 — Mandela had been slipped out of prison for the purpose. The two issued a joint communique committing themselves, in general terms, to peace.

And yet, even after the apartheid regime came to an end and Mandela was elected President in the early 1990s, Mandela and members of the African National Congress still had to apply for permission to enter the United States, and the State Department took the approach of letting in members of the ANC into the country on a case-by-case basis.

That is, until April 2008, when Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice said it was about time that Congress lifted those travel restrictions, as the U.S. otherwise had “excellent relations” with South Africa. “It is frankly a rather embarrassing matter that I still have to waive in my own counterparts — the foreign minister of South Africa, not to mention the great leader, Nelson Mandela,” she said.

In July 2008, President George W. Bush signed a bill into law that lifted that requirement — about four years after Mandela announced he was retiring from public life. The bill authorized “the Departments of State and Homeland Security to determine that provisions in the Immigration and Nationality Act that render aliens inadmissible due to terrorist or criminal activities would not apply with respect to activities undertaken in association with the African National Congress in opposition to apartheid rule in South Africa.” As Tom Casey, who was a State Department spokesman at the time, said, “What it will do is make sure that there aren’t any extra hoops for either a distinguished individual, like former President Mandela, or other members of the African National Congress to get a U.S. visa.”

But why did the change take so long? Though some have looked for a deeper reason for why the U.S. might want to keep Mandela out, the official answer usually cites mere bureaucratic oversight for explanation. As the 2008 bill’s bipartisan sponsors said in a statement, the change ended an “embarrassing impediment to improving U.S.-South Africa relations” and was, by that point, not a controversial idea.

“Nelson Mandela does not belong on a terrorist watch list – period,” said Sen. Sheldon Whitehouse. “This problem has caused injustice to South African leaders and embarrassment to the United States, and I’m glad it will be repaired.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Olivia B. Waxman at olivia.waxman@time.com