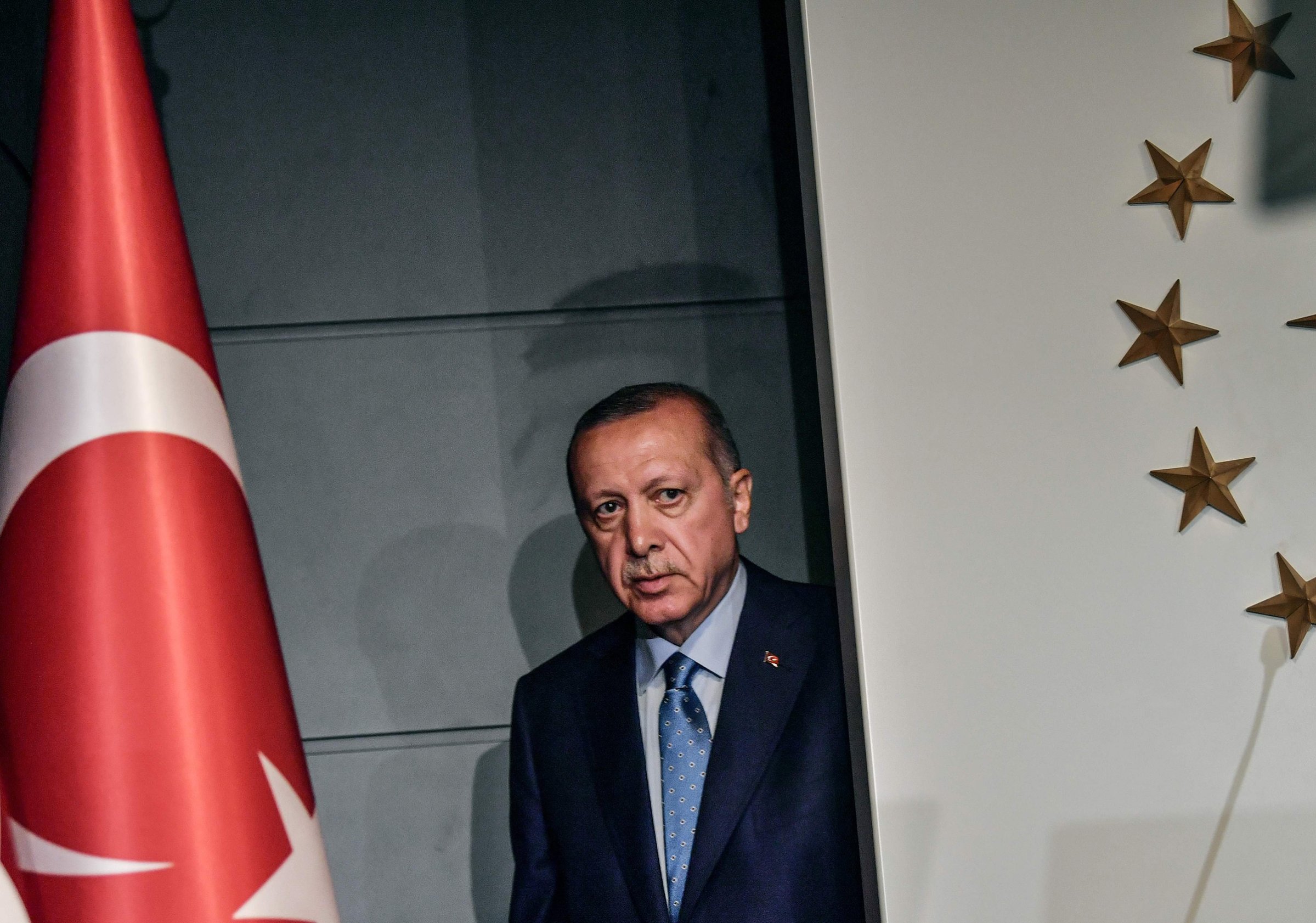

Now that Recep Tayyip Erdogan has been re-elected as President of Turkey, is the nation headed for “one-man rule,” as opposition candidate Muharrem Ince warned and international headlines suggest? Not so fast.

Erdogan has dominated Turkish politics for 15 years. He became Prime Minister in 2003, until term limits led him to run for President in 2014. He won and then called for a referendum to give his new job important new powers.

In July 2016, Erdogan survived a failed military coup and has since used a state of emergency–still in effect–to purge the country’s military, police and courts of enemies, both real and imagined. His government has arrested nearly 160,000 people; closed independent newspapers and television and radio stations; blocked tens of thousands of websites; and shut down hundreds of civil-society organizations.

In April 2017, Erdogan narrowly won his referendum and saw legitimate accusations of cheating. But to enjoy his new powers, he needed to see victory in another presidential election–which he did on June 24 of this year. Erdogan can now issue edicts with the force of law and pack the courts with loyal judges. The post of Prime Minister will no longer exist.

Here’s the catch: Erdogan’s Justice and Development Party (AKP) did not win a parliamentary majority. To form a government, the AKP has had to partner with the Nationalist Movement Party (MHP), which wants the government to spend more money to maintain a crackdown on Kurds inside and outside Turkey and to pursue a hawkish foreign policy that makes Turkey more active in Syria and less friendly to NATO allies in Europe and the U.S. That’s bad news for the President, Turkey’s economy, its internal security and its foreign policy.

While this is the first time Erdogan and the AKP have had to accept a coalition party, it is not the first time the AKP has failed to win a majority. In the previous instance, in June 2015, Erdogan called another election, and his party regained its majority five months later. But early elections are a much riskier proposition today. Turkey’s economy is in bad shape and getting worse: inflation is high, and its currency remains unsteady. The AKP also carried just 42.5% of the vote and is down 7 percentage points from the last election.

For five years, Erdogan will need backing from hardcore nationalist Devlet Bahceli, leader of the MHP, to pass his budgets, move legislation and avoid a parliamentary veto of his decrees. Bahceli understands the strength of his position. He’ll insist on an uncompromising approach to Turkey’s Kurdish separatists and their perceived civilian allies, which could intensify conflict in Kurdish regions as well as in Syria and Iraq, and provoke attacks in Turkish cities. He’ll also want Erdogan to increase criticism of the E.U. and the U.S. Erdogan has taken a hard line on all these subjects in the past, but Bahceli will raise the political cost of flexibility and a more conciliatory approach. And at a time when Turkey’s economy is unsteady, Bahceli will make it harder for Erdogan to push for less state spending and reform.

Erdogan now has more power than any other Turkish leader since the nation’s modern founder. Yet even though he and his party already control most of the media and the messaging–Ince got less than one-tenth of the TV airtime that Erdogan enjoyed–the President managed just 52.5% of the vote.

It won’t be easy to build an authoritarian system atop such a bitterly divided society. Dependence on allies will come at a cost. The weakening economy will take a political toll. There will be protests, and the government’s response will help determine Turkey’s stability. The President’s new powers will not free him of the obstacles ahead.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Biden Dropped Out

- Ukraine’s Plan to Survive Trump

- The Rise of a New Kind of Parenting Guru

- The Chaos and Commotion of the RNC in Photos

- Why We All Have a Stake in Twisters’ Success

- 8 Eating Habits That Actually Improve Your Sleep

- Welcome to the Noah Lyles Olympics

- Get Our Paris Olympics Newsletter in Your Inbox

Contact us at letters@time.com