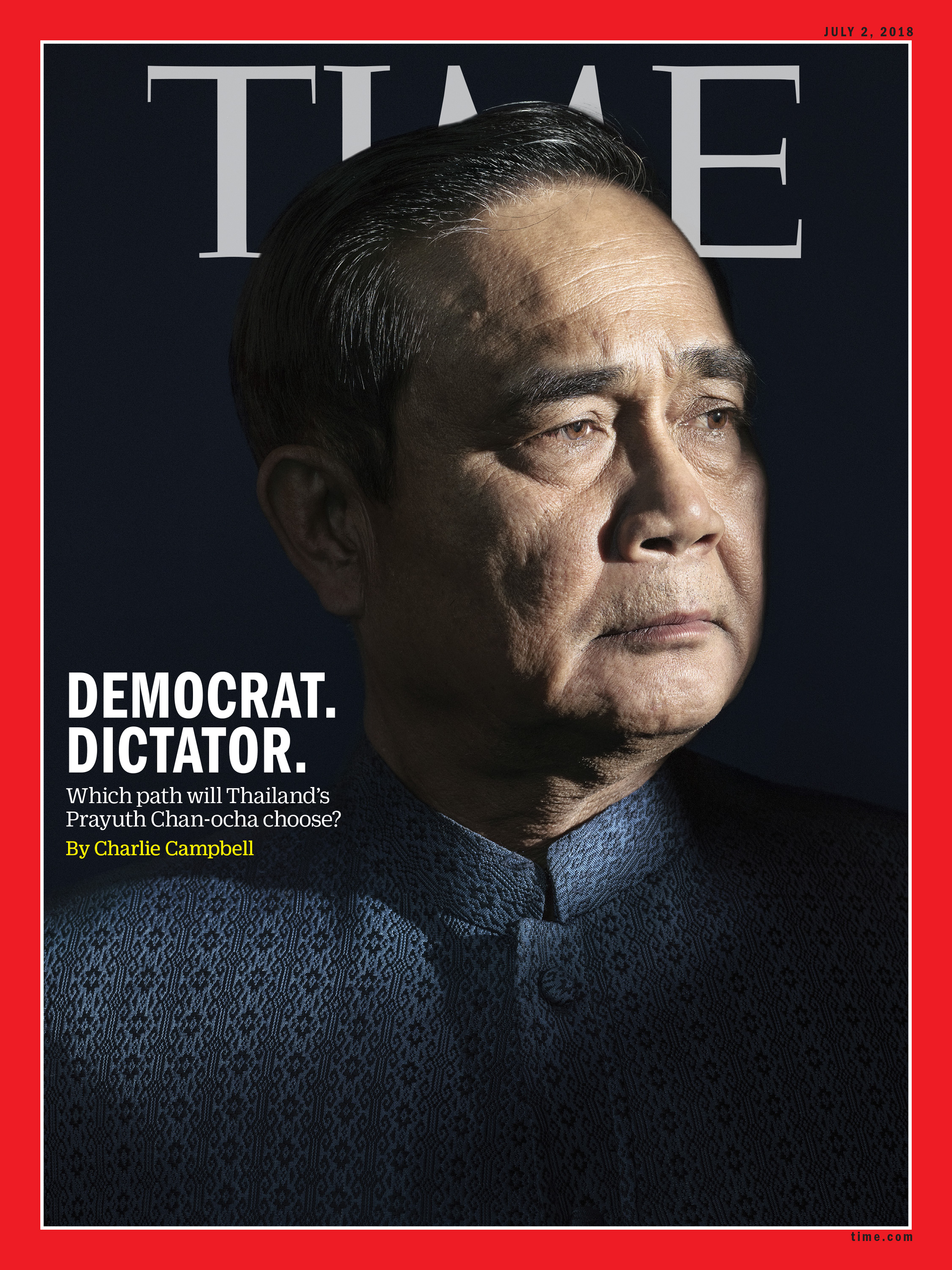

General Prayuth Chan-ocha appears at ease among the lavish trappings of politics. Thailand’s Prime Minister is never far from doting courtiers in Bangkok’s 1920s Government House, a neo-Gothic building stippled with classical nudes and one particularly plump jade Buddha.

The opulence is a far cry from what Prayuth experienced in his four decades as a soldier, when he was trained to brave enemy fire from jungle-swathed foxholes. Still, he expresses dissatisfaction with this coda to his career away from the barracks. He sits in a position of power, he says, only out of a sense of duty. “When people are in trouble, we, the soldiers, are there for them,” he tells TIME.

The question for Thailand is how long they will be there. Four years have passed since Prayuth, 64, seized power in a coup d’état. It was the 12th successful coup since the establishment of a constitutional monarchy in 1932, and Prayuth promised to quickly shepherd the Southeast Asian nation of 69 million back to democracy.

But the Thai people are still waiting to vote on their futures. Many here and in the region fear that under Prayuth’s watch, America’s oldest ally in Asia is undergoing a permanent authoritarian regression. It’s a pattern that has been replicated elsewhere in the region as China’s influence swells and President Trump pursues his “America first” doctrine.

Right now, the U.S. seems less committed than ever to smaller regional allies like Thailand in the 10-member Association of Southeast Asian Nations, or ASEAN. Although Trump welcomed Prayuth to the White House in October, the Thai leader says Washington now seems “somewhat busy with its own issues. There seems to be some distance between the U.S. and ASEAN.”

More from TIME

In terms of regional rivalry, there’s no competition. “The friendship between Thailand and China has existed over thousands of years, and with the U.S. for around 200 years,” Prayuth says. “China is the No. 1 partner of Thailand.”

Born in the northeastern province of Nakhon Ratchasima, Prayuth began his career at Chulachomklao Royal Military Academy, which is considered to be Thailand’s West Point. As a young officer, he won the Ramathipodi medal, the country’s top honor for gallantry in the field. “When I was young, patriotism was all about joining the army, fighting in the front line for your country,” he says. “I told myself that I had to dedicate my life for my homeland and the monarchy.”

The royal family is treated with almost divine reverence in Thailand. Prayuth strengthened ties with the royal household and earned himself the nickname Little Sarit, after Field Marshal Sarit Thanarat, who seized power through a putsch in 1957 and helped raise the monarchy to its paramount role in Thai society. Today every Thai household displays a portrait of the monarch as the highest picture in the room. And the country boasts some of the world’s strictest royal defamation laws, which are increasingly being used to crush dissent.

Many believe Prayuth’s coup was meant to ensure that Thailand’s elites remained in control during a sensitive time of royal succession. Thailand’s new King, Maha Vajiralongkorn, leads an unconventional lifestyle and does not command the same respect that his father did. Prayuth says simply that he took control to restore order. “I could not allow any further damage to be done to my country,” he says, with a dash of histrionics. “It was at the brink of destruction.”

Prayuth was only four months from mandatory retirement when he seized power on May 22, 2014, after six months of street protests against the elected government of former Prime Minister Yingluck Shinawatra. The demonstrations claimed at least 28 lives and left more than 700 injured. For more than a decade, Thailand has been wracked with color-coded street protests between the typically rural supporters of Yingluck and her brother Thaksin–who served as Prime Minister from 2001 to 2006–and their mainly urban opponents, backed by the powerful royal palace, military and judiciary. The pro-Yingluck faction wear red. Their opponents wear yellow.

Since 2014, Prayuth has returned Thailand to relative strength. Under the junta’s watch, GDP growth has risen to 4%, exports are at a seven-year high and a record 35 million tourists thronged Thailand’s beaches and temples in 2017. Infrastructure projects, like the $45 billion Eastern Economic Corridor of ports, railways and factories southeast of Bangkok, have been greenlighted. “These were not four years of empowerment, but it was the time to solve problems, overcome obstacles and build stability, security to move forward to the future,” says Prayuth.

Exactly what that future will bring remains opaque. Peaceful protesters are routinely detained. At least 1,800 civilians face prosecution in military courts, amid what Human Rights Watch describes as “an ever-deeper abyss of human-rights abuses.” Prayuth has a prickly relationship with the media. He once threw a banana skin at a reporter and threatened to “execute” those he considered unfair. In January, he brought a life-size cardboard cutout of himself to a press conference and placed it in front of reporters, telling them to “ask this guy.”

And he comes across as tone-deaf to the peoples’ woes. He hosts a weekly television show on which he bemoans the country’s ills and offers baffling remedies. To tackle poverty, he advised “working harder.” To avoid debt, he proposed “not going shopping.” He has complained of “black magic” and “curses” from opponents. On one rural outreach mission, he was photographed talking to a frog.

Prayuth also pens songs and poems to express himself, and released two commercial pop singles that received mixed reviews. “My songs may not be beautiful, but it’s a way to help me express my thoughts and communicate with the people,” he says. “Thai people love poetry.”

His attempt to install a new political system to ostensibly bring democracy back to Thailand still means the armed forces will act as a power broker. Although there will be elections, the military will appoint a third of the legislature and effectively retain a final say on key policy decisions. Prayuth says this will dilute the “winner takes all” system of majoritarian rule. “We cannot only care for the majority and neglect the minority like Thai democracy before,” he says.

Yet many activists feel they are further away from democratic elections than ever. The latest proffered date is February 2019, although figures from across Thailand’s political spectrum harbor doubts. “Mr. Prayuth is making every effort to stay in power,” says former Deputy Prime Minister Chaturon Chaisang.

Those who oppose him can suffer dire consequences. Nuttaa Mahattana, 39, is one of the five leaders of the “We Want to Vote” movement, who were detained at a peaceful protest on the fourth anniversary of Prayuth’s coup. She faces various draconian charges, including sedition, which carries a maximum sentence of seven years’ imprisonment. “A junta doesn’t belong in a democratic system,” Nuttaa tells TIME from behind the bars of her squalid cell in central Bangkok. “Most people want to see democracy. They just don’t want to see their family members getting arrested.”

Prayuth is unmoved when pressed about the fate of demonstrators. “We have been rather lenient,” he says. “If we allowed them to demonstrate freely, it might become too difficult to move forward to democracy.”

This shift toward a loose authoritarianism revolving around a single figure is becoming a pattern across ASEAN. The Philippines–which, like Thailand, is a U.S. treaty ally–has moved firmly into China’s orbit under populist President Rodrigo Duterte, who has been criticized by the West for his brutal drug war. In Myanmar, international censure regarding the ethnic cleansing of the Rohingya minority rings hollow as Chinese investment floods into the military-dominated country. And the Beijing-backed government of Cambodia’s Prime Minister Hun Sen has cracked down on opposition politicians and critics in recent months.

Historically, Thailand was something of an exception to the rule when it came to U.S. relations. The much-beloved King Bhumibol Adulyadej, who died in 2016, was born in Cambridge, Mass. In the 1950s and ’60s, the country was a bulwark against the communist fervor sweeping Southeast Asia, and during the Vietnam War, Bangkok was a vital staging post for U.S. troops. In 1969, President Nixon paid tribute to the U.S.’s “deep spiritual and ideological ties” with Thailand.

The U.S. has since lost top trading-partner status to China. After Prayuth’s coup, Washington suspended all nonessential official visits and one-third of U.S. aid to Thailand, condemning the intervention as having “no justification.” China stayed silent.

Since then, military cooperation between Beijing and Bangkok has ramped up. Thailand has purchased 49 Chinese tanks and 34 armored vehicles worth over $320 million, plus three submarines at more than $1 billion. There are plans for a joint Sino-Thai commercial arms factory in the northeastern province of Khon Kaen. Beijing’s $1 trillion Belt and Road Initiative–a trade and infrastructure network tracing the ancient Silk Road–stands to further boost its regional clout.

As a result, liberal democracy is increasingly no longer seen as the fastest route to prosperity. In Beijing, President Xi Jinping has ramped up censorship, purged opponents and removed presidential term limits, effectively letting him rule for life. That model looks appealing, especially when set against the chaos gripping Washington. “People see successes in authoritarian countries and so grow impatient with the messy democratic process,” says former Thai Prime Minister Abhisit Vejjajiva.

The sharp end of Prayuth’s rule is felt most dramatically in the populous north and northeast, where Yingluck remains popular. Soldiers tear down pro-Yingluck posters and scold her supporters. “They even complained that I had dyed my hair red,” says Yingluck supporter Paanoi Udomsri, 68, at the market stall where she sells peanut brittle.

Meanwhile, rising unemployment and the rolling back of assistance programs have hurt northerners like Suwanna Khanadham, who owns a canteen in Chiang Mai selling khao soi, or curry noodle soup. The price of palm oil has almost doubled and that of a single lime has soared from 15¢ to 40¢. “The soldiers don’t have any vision for how to improve the country,” complains Suwanna. “They only know how to control.”

Prayuth’s plan of a quasi-democracy guided by military generals relies on people like Suwanna not returning to the streets. “If we don’t have elections in February, I think it will be the final straw,” says Thida Thavornseth, leader of the Pro-Yingluck Red Shirt protest faction.

There are other signs that tensions may soon reach a critical point. Corruption allegations against junta brass hats have stoked public fury. Rubber farmers from Thailand’s south, who supported the coup, feel betrayed that the junta has failed to prop up falling rubber prices. Others are enraged by crackdowns on land-rights protests. “When Prayuth comes on television, we just turn it off,” says primary-school teacher Juraiporn Tapin, 61, sneering. “We all want rid of the military as soon as possible.”

John Winyu, who hosts the satirical online show Shallow News in Depth, says that on social media young Thais are switching from fawning over K-pop stars to political griping, wielding the hashtag #WeWanttoVote. “People are starting to catch on that the soldiers will be here forever unless we do something,” he says.

Prayuth, meanwhile, insists that his dictatorship is reluctant and temporary. “I never imagined becoming Prime Minister in this way,” he says. “It was the hardest decision of my life.” So he definitely won’t stay in power past February? “That depends on the situation and the people,” he says with a shrug. “I have no control over this.” Millions of Thais feel the same way.

–With reporting by FELIZ SOLOMON/BANGKOK

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How Donald Trump Won

- The Best Inventions of 2024

- Why Sleep Is the Key to Living Longer

- Robert Zemeckis Just Wants to Move You

- How to Break 8 Toxic Communication Habits

- Nicola Coughlan Bet on Herself—And Won

- Why Vinegar Is So Good for You

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Write to Charlie Campbell/Bangkok at charlie.campbell@time.com