Few presidents have been as excited about pardon powers as Donald Trump.

In recent months, Trump has issued a rare posthumous pardon to boxer Jack Johnson and a much more contemporary one to conservative commentator Dinesh D’Souza. He has commuted the sentence of Alice Johnson, in the wake of lobbying by Kim Kardashian West, and drawn a rebuff from Muhammad Ali’s attorney for suggesting that the boxer might also receive a posthumous pardon, even though his name was already cleared by the Supreme Court.

He even asked NFL players, amid continued conflict over protests at football games, to suggest people he should pardon — though as of Friday none had taken him up on the idea, and the request drew criticism for seeming to misunderstand the reasons behind the protests.

Some have argued that Trump is using these high-profile pardons — especially of D’Souza and former vice presidential adviser Scooter Libby — to send signals to associates being targeted by Special Counsel Robert Mueller’s investigations that he may pardon them if they don’t cooperate, prompting his attorney Rudy Giuliani to clarify that was not his intention. (Trump and his lawyers have even asserted, contrary to public opinion, that he could pardon himself if he wanted to.)

But Trump has long been a fan of executive action — witness the signing ceremonies he schedules for executive orders — and it seems likely that he’s going to continue issuing pardons.

With that in mind, we asked historians for some notable figures from American history that they think could merit a posthumous pardon. Not every suggestion was literal (many never received the federal conviction that would open a person up for such a pardon, and one is a fictional character) but all were thought-provoking. Here are a selection of the responses. — Lily Rothman

Matthew Lyon (1749-1822)

My nominee for a posthumous presidential pardon is the intriguing Vermont congressman Matthew Lyon. A member of Thomas Jefferson’s Democratic-Republican party, Lyon was convicted in 1798 of violating the Sedition Act and sentenced to four months in jail. The Sedition Act prohibited malicious criticism of the federal government, Congress or the president. In his own newspaper, Lyon editorialized that Federalist President John Adams had an “unbounded thirst for ridiculous pomp, foolish adulation, and selfish avarice.” Under Jefferson’s subsequent presidency, the Sedition Act was repealed as a gross violation of First Amendment free speech guarantees. Lyon is the only person ever elected to Congress while serving a jail sentence. In 1840, Congress passed a bill refunding Lyon’s $1,000 fine and other costs incurred from his conviction.

Barbara A. Perry is Presidential Studies Director at the University of Virginia’s Miller Center, a non-partisan think tank focused on the presidency.

Slave Revolt Leaders

I can think of many people in the past worthy of pardons. At the top of my list are the leaders of major slave revolts or suspected conspiracies: Gabriel Prosser (1800), Charles Deslondes (1811), Denmark Vesey (1822) and Nat Turner (1831). Not all of these men who led rebellions received formal trials; for example, the U.S. army and Louisiana militia that put down the German Coast rebellion summarily executed Deslondes.

Christine Heyrman is Robert W. and Shirley P. Grimble Professor of American History at the University of Delaware

John Anthony Copeland Jr. (1836-1859)

The son of a formerly enslaved father and a free mother, John Copeland Jr. made history when he participated in the raid at Harper’s Ferry along with abolitionist John Brown and several others. They attacked the federal arsenal and tried to lead a large-scale rebellion to end slavery. Copeland was tried, convicted and hanged for murder on Dec. 16, 1859. He should receive a posthumous pardon for fighting for the freedom of all American citizens.

Daina Ramey Berry is Associate Professor of History at the University of Texas, Austin

Those Convicted Under the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850

In 1851, African-American lawyer Robert Morris and abolitionist Lewis Hayden were tried in federal court in Boston for allegedly aiding accused Shadrach Minkins to escape proceedings under the 1850 Fugitive Slave Act. Morris and Hayden were not found guilty — nevertheless, approximately 300 African Americans were returned to slavery after the Act was passed, as well as other Americans who were charged under the Act for aiding alleged fugitives to escape.

Mary Sarah Bilder is Founders Professor of Law at Boston College Law School

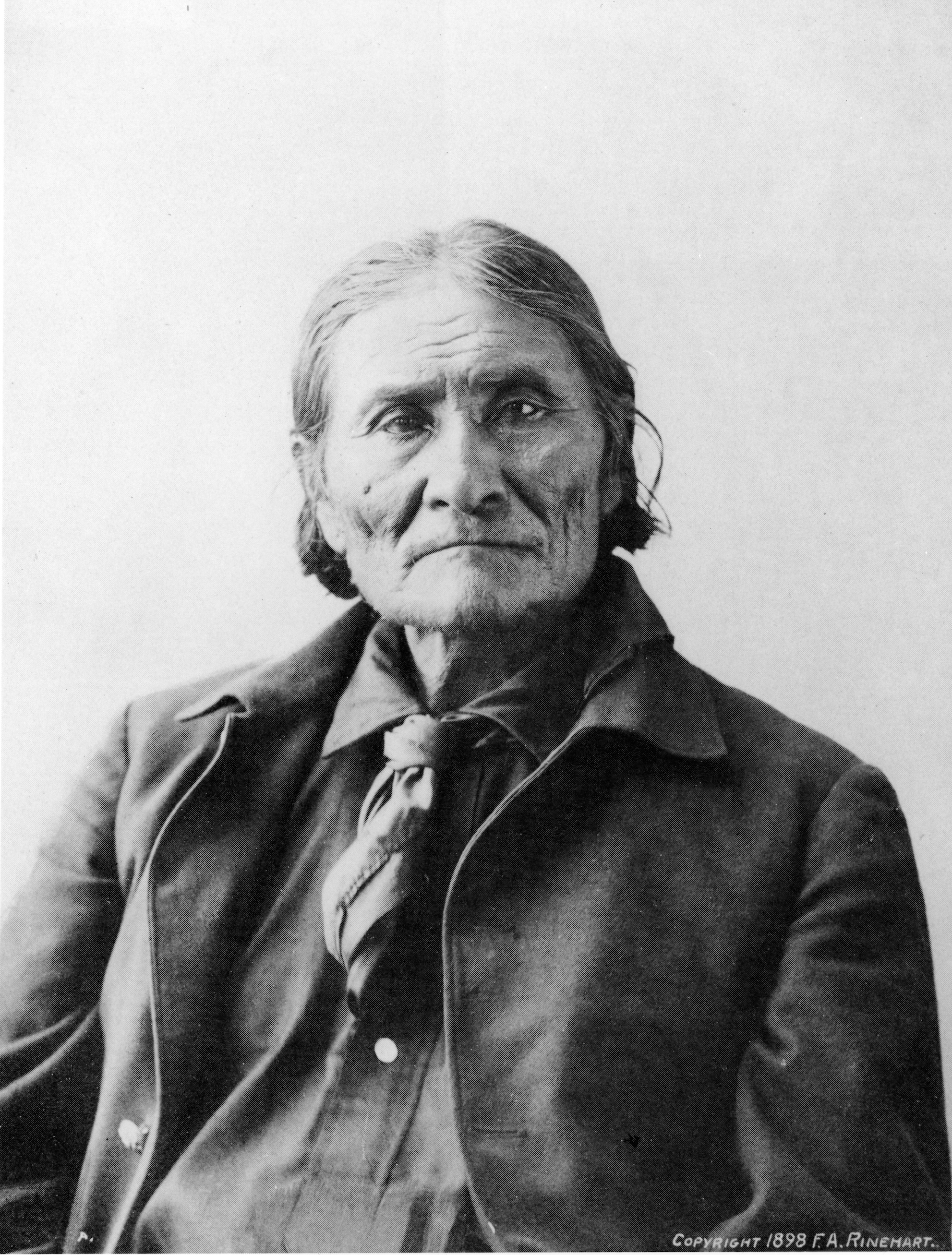

Geronimo (1829-1909)

The Chiricahua Apache warrior and leader was a successful holdout from U.S. Army until he surrendered in 1886. He was held in a series of army prisons until his death in 1909 in the Fort Sill, Okla., army prison. He was allowed out of prison to attend several World’s Fairs in St. Louis and Chicago, where the elderly Indian prisoner delighted fairgoers while dressed in his “native costume,” still under the eye of prison officials. If you compare Native American chiefs warriors to Confederate Generals or soldiers in the Civil War, who fought against the United States at the same, their treatment was entirely different: Confederate soldiers were sent home with their weapons and but Native American soldiers were shot, hanged or imprisoned.

Anne F. Hyde is Professor of History at the University of Oklahoma

Eugene V. Debs (1855-1926)

I would nominate Eugene Victor Debs, long-time leader and presidential candidate of the Socialist Party of America. In 1918 Debs was convicted of sedition for giving an antiwar speech and sentenced to federal prison. His sentence was commuted to time served in 1921 by President Harding and he was released from jail, but he was never pardoned. He was a remarkable figure in American history, and was basically convicted for political activism.

Tyler Stovall is Distinguished Professor of History and Dean of Humanities at the University of California Santa Cruz

Dr. Richard Kimble of The Fugitive (fictional)

A proper presidential pardon requires evidence gathering and deep reflection, neither of which has been apparent in the recent decrees and related speculation. So my only suggestion for this president would be Dr. Richard Kimble, a fugitive from 1963-1967. He fits all of the apparent requirements: celebrity, invented drama, a narrative re-created weekly and an exoneration that makes the pardon superfluous.

James Grossman is Executive Director of the American Historical Association

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com