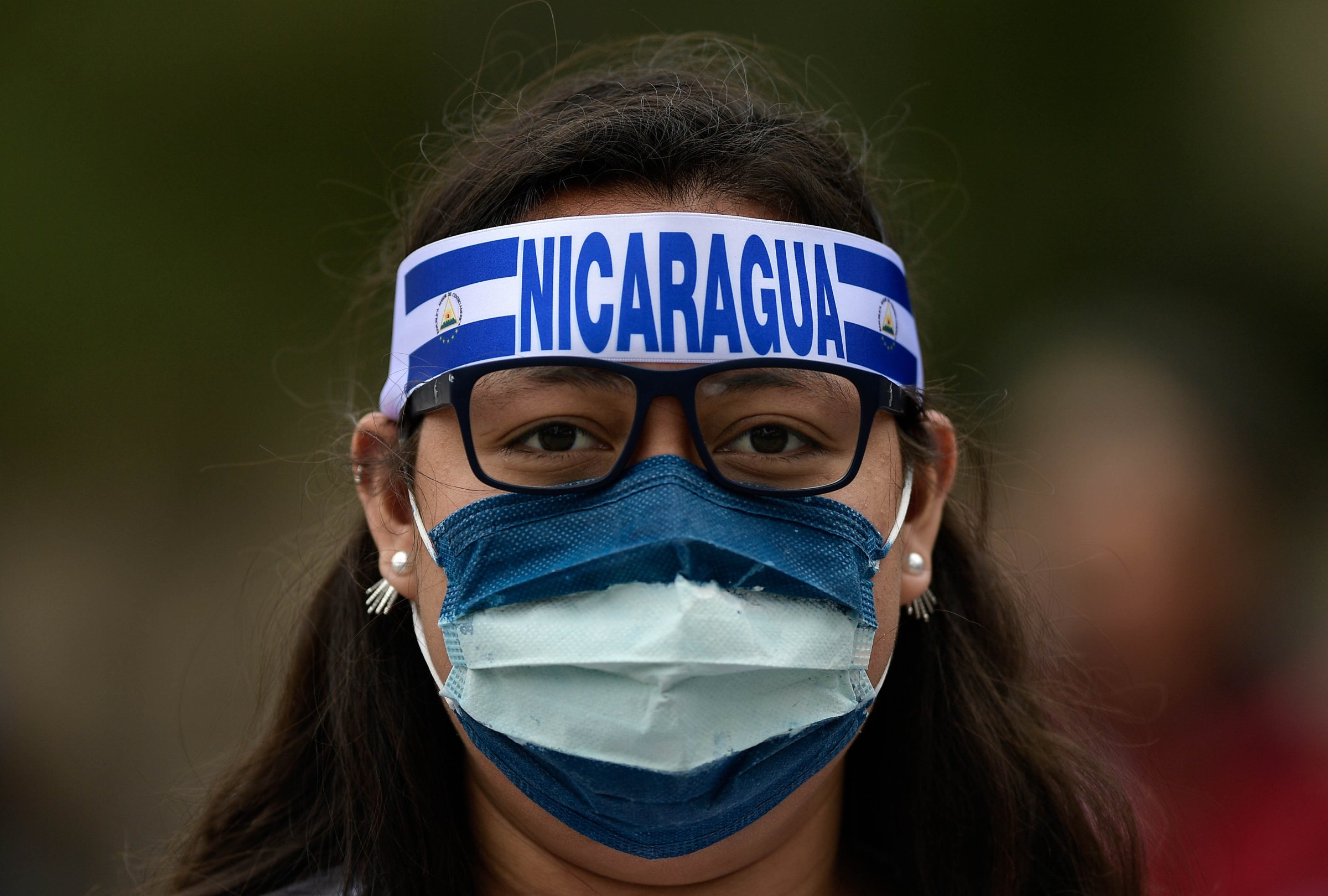

While the world watches Venezuela’s slow, cancerous death, Nicaragua is in full cardiac arrest. Since protests began on April 18, the government of President Daniel Ortega has been accused of using “lethal force” and at least 146 people have died. Hundreds more are wounded or missing and the body of a U.S. citizen was found shot dead on June 2. Without international intervention, the collapse of my country could create a new cycle of war and destruction in this precarious region.

I am a mother and a businesswoman, managing several American franchise restaurants across Nicaragua with over 650 employees. The first tremors came in April, when demonstrations against the Ortega regime, largely led by students, started in Managua and quickly spread to cities across the country. The government’s reaction was swift, and in the first few days dozens were killed by police and paramilitary forces using live rounds of ammunition.

On May 30, Nicaragua’s Mother’s Day, I marched with 250 of my employees to remember the children killed in that initial crackdown. Planned by the victims’ mothers, the peaceful march descended into chaos when professional sharpshooters with modern, long-range weapons opened fire with deadly accuracy on innocent marchers. We watched in horror as these pro-government Sandinista mobs managed to kill with precise, single shots to the head from high-rise buildings and atop the national baseball stadium. As we ran for cover to one of our nearby restaurants, we saw protesters fall and bodies pass by in makeshift ambulances. I consoled one grieving young man still covered in the blood and brain matter of a close friend.

Nicaragua’s Catholic bishops called the bloodshed an “organized and systemic aggression”—but it has since worsened. The Mothers’ Day massacre has been nationalized, and systematic kidnapping and torture has been added to the mix. Several employees and acquaintances have been brutally beaten by government thugs, while others have been abducted and tortured for refusing to pay fealty to the Sandinista party leadership.

Nicaragua’s tenuous economy is now threatening to collapse. My goal is to keep our team members safe and employed. If I lay off anyone, their families will starve. There are no jobs, or even functioning charitable organizations to feed the unemployed or impoverished. Some of our restaurants are only open two to three hours a day due to roadblocks and riots, while others are inaccessible with fighting outside. We have even shifted to what we call “war menus” with lower prices and longer shelf-life ingredients. These may seem like trivial concerns in a country where murder, disappearances and extortion have become the norm, but in the face of growing anarchy, you do what you do best. In my case, that means organizing and putting people to work.

Nicaragua has been quietly heading down this path for over a decade. Relative economic stability masked the slow accumulation of power by President Ortega and his wife, Vice President Rosario Murillo. As democratic institutions were dismantled by El Comandante’s regime, their cronies grew in wealth and the stage was set for an enduring Ortega dictatorship.

Since the early 2000s, much of Latin American witnessed a relatively long period of political stability. With the exception of Cuba, democratically elected governments began to take hold and economies started to grow. Venezuela’s implosion and Nicaragua’s misrule and growing violence threaten to reverse this progress and destabilize the region. Ortega and Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro provide each other mutual support—an “axis of misery”—while Russia and Iran lurk in the shadows.

The United States has long viewed security and prosperity in Nicaragua and its neighbors as key to regional stability and its own national security. Drug trafficking, immigration and terrorism are all made worse by instability in Central America. Nicaragua’s inferno shows no sign of abating and it is a situation ripe for exploitation by drug cartels and political opportunists. One tool the U.S. administration should employ in response is the Global Magnitsky Act, the U.S. law that allows the President to impose visa bans and targeted sanctions on individuals anywhere in the world responsible for committing proven human rights violations or acts of significant corruption.

Nicaragua’s famous poet Rubén Darío wrote over a century ago, “Si la patria es pequeña, uno grande la sueña” (“If the homeland is small, one dreams it large”). I am perhaps naïve to think my small country could be a model for democratic reform and human rights, particularly given its post-colonial and revolutionary history. Growing tyranny extinguishes hope, and our daily focus turns to survival and emigration. But if I were to “dream it large,” our neighbors to the north would cast a glance at our beleaguered country and see something worth saving, even if it’s purely in their own self-interest.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Introducing the 2024 TIME100 Next

- The Reinvention of J.D. Vance

- How to Survive Election Season Without Losing Your Mind

- Welcome to the Golden Age of Scams

- Did the Pandemic Break Our Brains?

- The Many Lives of Jack Antonoff

- 33 True Crime Documentaries That Shaped the Genre

- Why Gut Health Issues Are More Common in Women

Contact us at letters@time.com