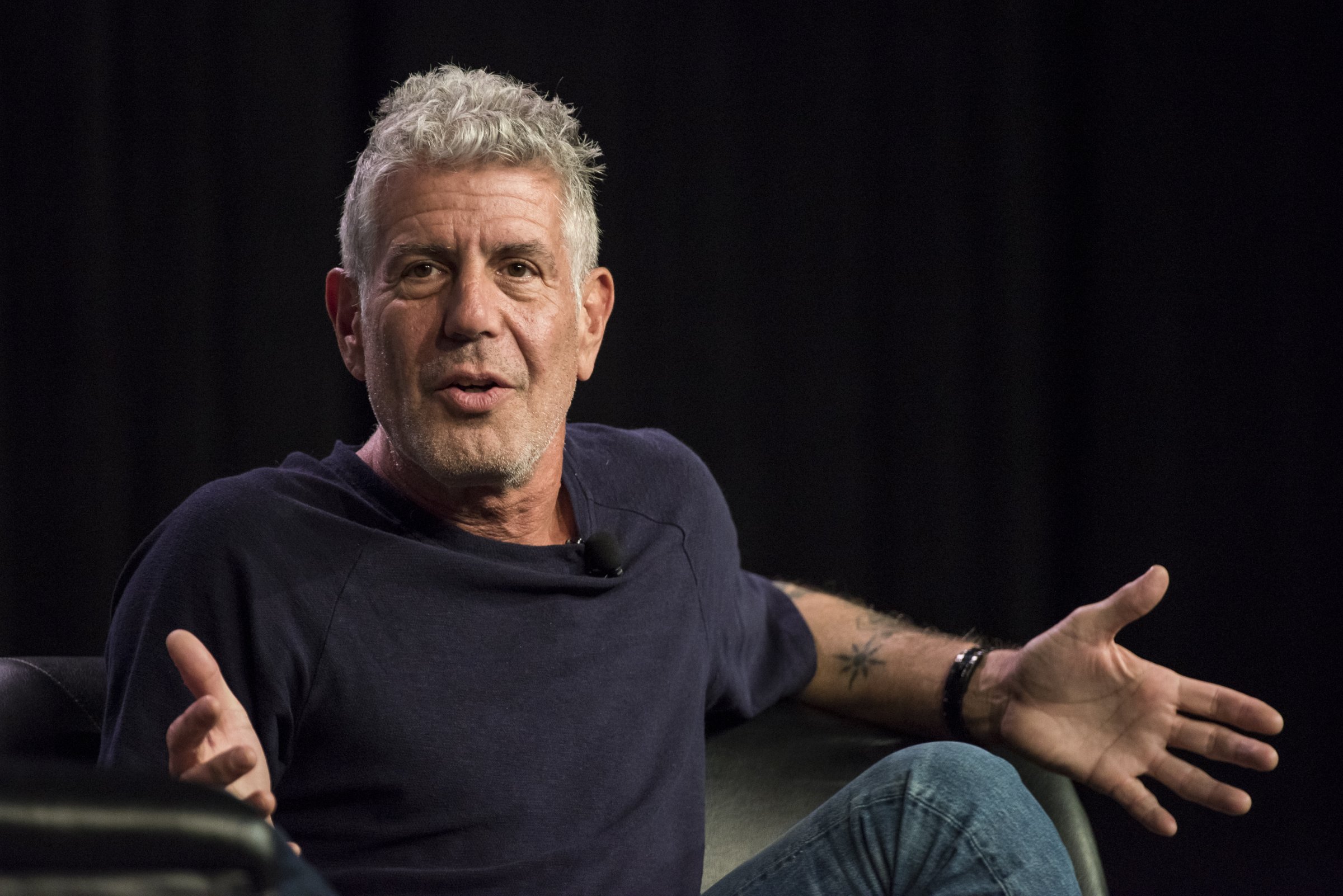

Two high-profile deaths by suicide — those of fashion designer Kate Spade and chef Anthony Bourdain — were met with an outpouring of grief from fans this week. But mental health professionals say they should also serve as an important reminder to support other people who may be struggling, given rising suicide rates across nearly every segment of the U.S. population.

“We often don’t take time to reach out to those we care about and love, even when we notice there’s a concern,” says Nadine Kaslow, a past president of the American Psychological Association and a professor at Emory University School of Medicine. “People are often worried that if you ask someone [about suicide] you increase their likelihood of dying by suicide. But I think the truth is, you really make it less likely, because they know there’s somebody who cares about them, and you can help them get help.”

But how can you tell someone needs your help? Dr. Jeffrey Lieberman, chair of psychiatry at New York-Presbyterian/Columbia University Irving Medical Center, says people may act depressed, become withdrawn or disinterested or make ominous comments before a suicide attempt. Significant changes in behavior or affect may be warning signs as well. “It’s not something that spontaneously, abruptly happens without any preceding process,” Lieberman says. “The idea that suicide is not preventable is completely fallacious.”

That said, there’s not typically one “cause” of suicide. Although mental health conditions are a significant risk factor, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported that more than half of people who died by suicide in a recent study did not have a known preexisting mental health condition. (Lieberman says, however, that this may be because many mental illnesses go undiagnosed or untreated.) Other factors, such as traumatic events, life stressors and substance use, may play a role as well, which underscores the necessity of being there for your loved ones during tough times.

Heavy conversations like these are best done in person, Kaslow says, because you may be able to pick up on non-verbal cues that aren’t obvious over the phone or through text. Joel Dvoskin, a psychologist at the University of Arizona Medical School, also says you should listen more than you talk. “Telling someone how they feel is seldom a successful strategy for anything,” Dvoskin says. “Asking them how they feel is often a good strategy.”

It may be especially important to reach out to friends, family and colleagues in the wake of high-profile deaths like Spade’s and Bourdain’s. Research has shown that “suicide contagion” — a potential increase in suicidal behavior after people are exposed to suicide, either directly or through media coverage — is a real and troubling phenomenon. After actor Robin Williams died by suicide in 2014, for example, researchers tracked a 10% increase in suicide deaths over the next four months, likely in part due to a high volume of detailed news stories.

If someone indicates that he or she is thinking about suicide or self-harm, it’s best to help them connect with a mental health professional — but this may be easier said than done, Lieberman says. The stigma of seeing help, long waitlists for specialists and disparity in access to mental health resources can all interfere with getting treated.

In these cases, Kaslow says, you may need to find help elsewhere. Suicide prevention hotlines, apps, support groups and religious communities, while not a replacement for treatment, may be helpful to those who are struggling. And if someone is at immediate risk of harming him or herself, Kaslow says, it’s best to seek care from an emergency department or primary care doctor.

“It’s not your job as a friend or a family member to evaluate the level of care somebody needs,” she says. “If you’re really concerned about somebody being suicidal, I don’t believe a hotline is enough. I don’t think an app is enough. You have to get them care now.”

And you’ll never know whether someone needs care if you don’t ask, Dvoskin says.

“It’s on all of us to take more responsibility for our own health and the health of our loved ones, both physical and emotional,” Dvoskin says. “I tell people, ‘You may have prevented a suicide in your life and have no idea, because you were kind to somebody not knowing that they were in a moment of utter despair.’ As long as it’s done in a respectful and non-intrusive way, I don’t think it can hurt anything — and it might help.”

If you or someone you know may be contemplating suicide, call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-8255.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How Donald Trump Won

- The Best Inventions of 2024

- Why Sleep Is the Key to Living Longer

- Robert Zemeckis Just Wants to Move You

- How to Break 8 Toxic Communication Habits

- Nicola Coughlan Bet on Herself—And Won

- Why Vinegar Is So Good for You

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Write to Jamie Ducharme at jamie.ducharme@time.com