For Andre Agassi, playing tennis was just a warmup.

The former star, who played professionally for 20 years and spent 101 weeks as number one in the world, says his sporting accolades can’t compare with what he’s accomplished since. “At the time tennis felt really important,” he says. “But what you can do off the court is generational.”

Agassi began to envision a future after the roaring crowds and rush of competition mid-way through his tennis career when, at the age of 23, he launched the Andre Agassi Foundation for Education.

That’s why the 48-year-old could be found on a recent June morning playing an exhibition game of mixed doubles under the Eiffel Tower—albeit against two children—at the Longines Future Tennis Aces tournament, which welcomed 40 players under the age of 13 from 20 countries around the world. Between points, Agassi and his wife, the German athlete Steffi Graf, shared a kiss. (Both Agassi and Graf are ambassadors for the Swiss watchmaker, Longines, which supports their respective foundations.)

“It is amazing to watch cultures breed the next generation of player that didn’t exist before and to watch them push each other to different levels,” he says. Watching Asia come into the equation, for instance, has made the game more exciting; at the tournament in Paris, there are players from Korea, Japan, India and China. But ultimately, he says, “tennis is about one on one. That applies across the globe.”

Read more: Andre Agassi says these are the tennis players to watch

It was here at the French Open in 1999 that Agassi completed his collection of eight Grand Slam singles championships, the same year that Graf won her sixth and final singles title in Paris. Agassi and Graf were also the first tennis players in history to win career “Golden Slams”—winning all four of the sport’s majors and Olympic singles, something only Rafael Nadal and Serena Williams have gone on to accomplish.

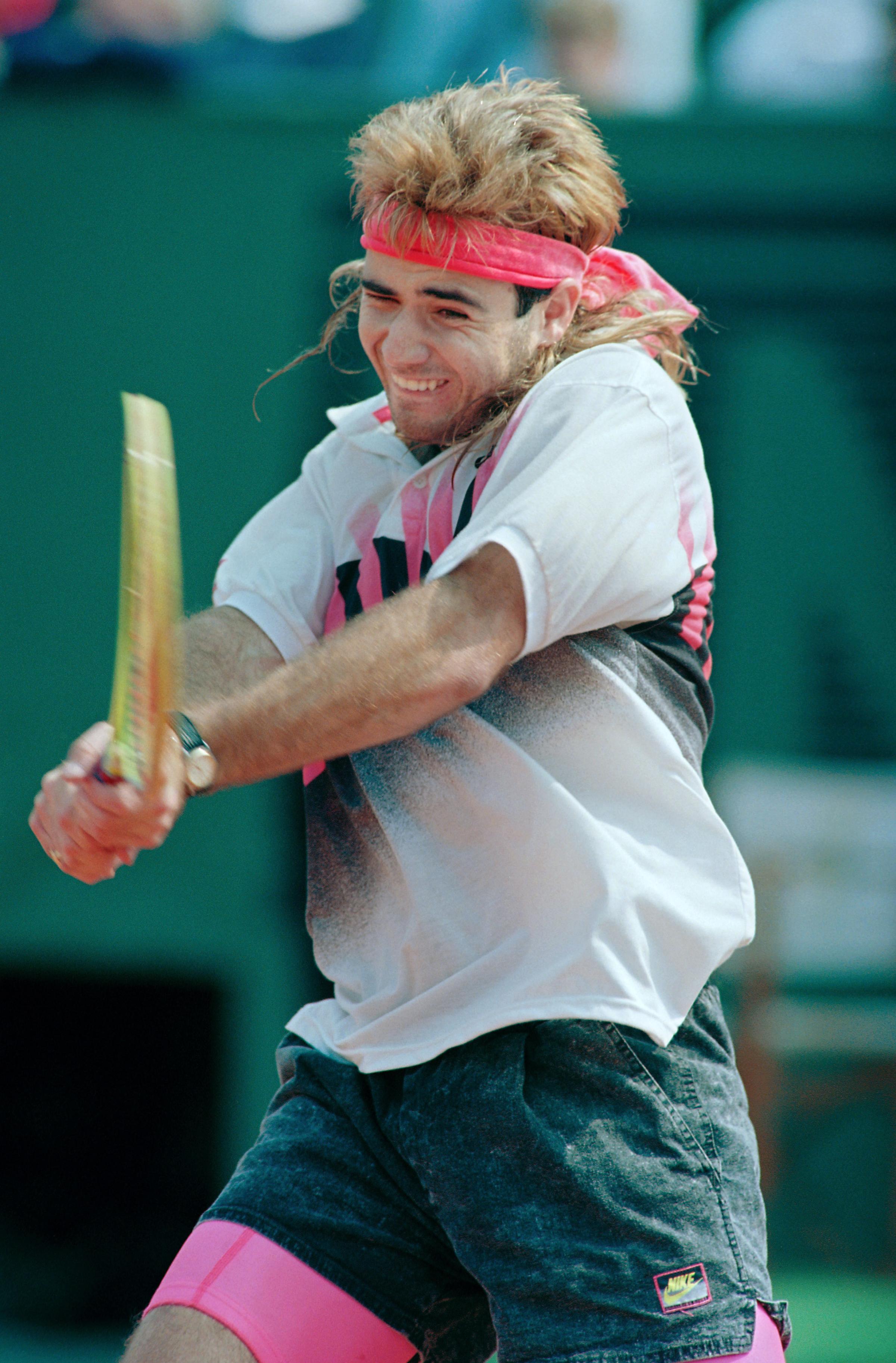

For Agassi, it was one of the most extraordinary comebacks in modern tennis: he had slipped from number 1 in the world in 1995 to a ranking of 141 two years later, only to rise back up to number 1 in 1999. To those who knew Agassi as a “punk” with a mullet and acid-washed jeans, his evolution was striking.

But the star who resented everything in the tennis world managed to find a new motivation to keep going—and a way to transition out of tennis. In 2001, he opened the Andre Agassi College Preparatory Academy, a charter school for underprivileged children in his hometown, Las Vegas. Since then, he has partnered with an investment fund and financed the construction of more than 80 charter schools across the U.S.

“I knew at 18 years old that I can’t be inspired just for the sake of winning a tennis match,” he says. “Giving opportunity to children through education became my passion for staying on a court.”

Changing Courts

In his acclaimed 2009 memoir, Open, Agassi confesses that after winning a slam, he knew something very few people did: “A win doesn’t feel as good as a loss feels bad.” That sentiment would no doubt resonate with some of the under-13 players, who have spent days training and competing against each other in Paris, to reach the finals—only to lose a match. Brushing away tears to smile for selfies, their disappointment is palpable.

“Growing up playing any sport with dreams of achieving, you need to keep it in context,” Agassi says. Seeing some of the children in Paris being so hard on themselves when they fail brings back memories of his own adolescence, out on the court with no one else to rely on. “To really achieve the highest level, you spend a third of your life not preparing for two-thirds of your life. You have to have a realistic understanding of what your expectations are, and then focus on getting better, not on winning or losing.”

Now that Agassi has left the court, he can channel his competitive nature into the foundation—where rewards are shared, and so are disappointments. But it wasn’t always easy, playing what he calls “the loneliest of sports.” In Open, the tennis star recounted his battle with depression, revealed how he used crystal meth and lied to the Association of Tennis Professionals tour after failing a drug test in 1997, and detailed his short-lived marriage to American actress Brooke Shields. Most striking of all, however, was Agassi’s intense hatred of the game he had mastered.

“I play tennis for a living even though I hate tennis, hate it with a dark and secret passion and always have,” he wrote. He describes in harrowing detail the prison created for him by the adults in his life, beginning with his father, who built a backyard court behind their house in the desert outskirts of Las Vegas. An Armenian Christian who grew up poor in Iran, Mike Agassi was a former boxer determined to raise a champion. Later, Andre attended a Florida tennis academy run by coach Nick Bollettieri, where “the constant pressure, the cutthroat competition, the total lack of adult supervision […] slowly turns us into animals.”

Speaking to TIME at the Georges V hotel in Paris, the ghosts of Agassi’s childhood come to life as he describes the experiences that sparked his journey into philanthropy. “As a child, I never had a choice,” he says. Though he loved learning, six hours a day of tennis made it almost inevitable that he would end up a great tennis player instead of a successful pupil.

“I’m an eighth-grade dropout,” Agassi says twice during our 30-minute conversation, acutely conscious of what he missed out on in life. And so his goal from very early on was “to use education as a vehicle to create choice for those kids that reminded me of myself.” During his career, Agassi earned $31 million in prize money; he has gone on to raise a further $185 million for the Andre Agassi Foundation for Education, hoping to tackle the “brokenness” of the U.S. education system. He reaches 65,000 lives on an annual basis, he says—but feels it’s far from enough.

His biggest frustration is that there’s no real advocate for children—no representative union for kids to air their concerns. “Everybody comes to the table with their agenda except what’s best for the child,” he says. “There’s a long waiting list of underserved kids that are just not getting the chance to fight for their futures.”

On a more personal level, thinking about what’s best for his own children—Graf and Agassi have a son, Jaden Gil, 16, and a daughter, Jaz Elle, 14—means constantly balancing a high standard of expectation with the love and acceptance of who they are. Both Graf and Agassi had domineering fathers and while their son has developed a passion for baseball, Agassi says it’s crucial his children know “they have a safe place to come to, that I’m going to nurture and guide them in their dreams and objectives.” At the same time, he says, if they want to succeed, they do need to be better than anybody else.

Agassi’s hatred of the game doesn’t burn so fiercely as it did when he wrote Open. In fact, he says today he loves the game for the platform it offered him. “My greatest connection on a tennis court was impacting people for a few hours—giving them a break from their lives, giving them an experience, hopefully a memory for a lifetime,” he says. Off the court, though, there’s the possibility of something much greater: creating change that will affect present and future generations of Americans. “There’s no comparison to me. I wake up with much more purpose today than I did when I played tennis.” It seems Agassi’s mastery of comebacks wasn’t just for the tennis world after all.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Caitlin Clark Is TIME's 2024 Athlete of the Year

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Naina Bajekal/Paris at naina.bajekal@time.com