With binoculars held up to her eyes, Christine Cornell craned forward to look past the court marshals standing in front of her to catch a glimpse of one of the most hated men in America.

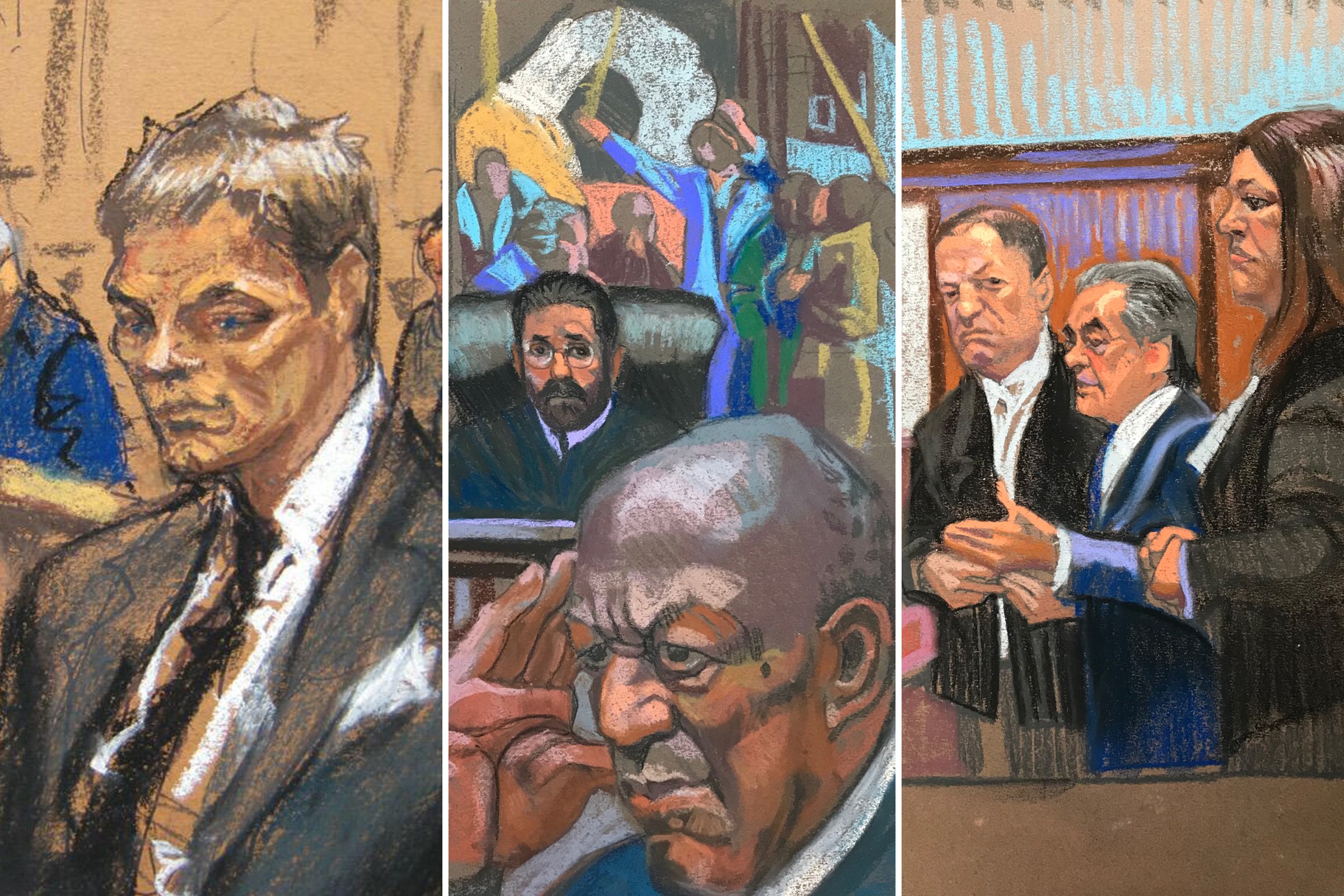

Cornell, with pastels and toned paper in hand, began to sketch disgraced film producer Harvey Weinstein as he appeared in court for the first time last week. Her sketches of Weinstein, which showed the producer appearing disgruntled in the courtroom, took her about a half hour to create and were just the latest high-profile figure she captured on the job as a courtroom sketch artist with a career. Over the last few decades, she has sketched Bill Cosby, Donald Trump, Mick Jagger and Tom Brady, among a large swath of other figures, as they appeared in court over the years to give testimonies or answer to offenses varying in severity.

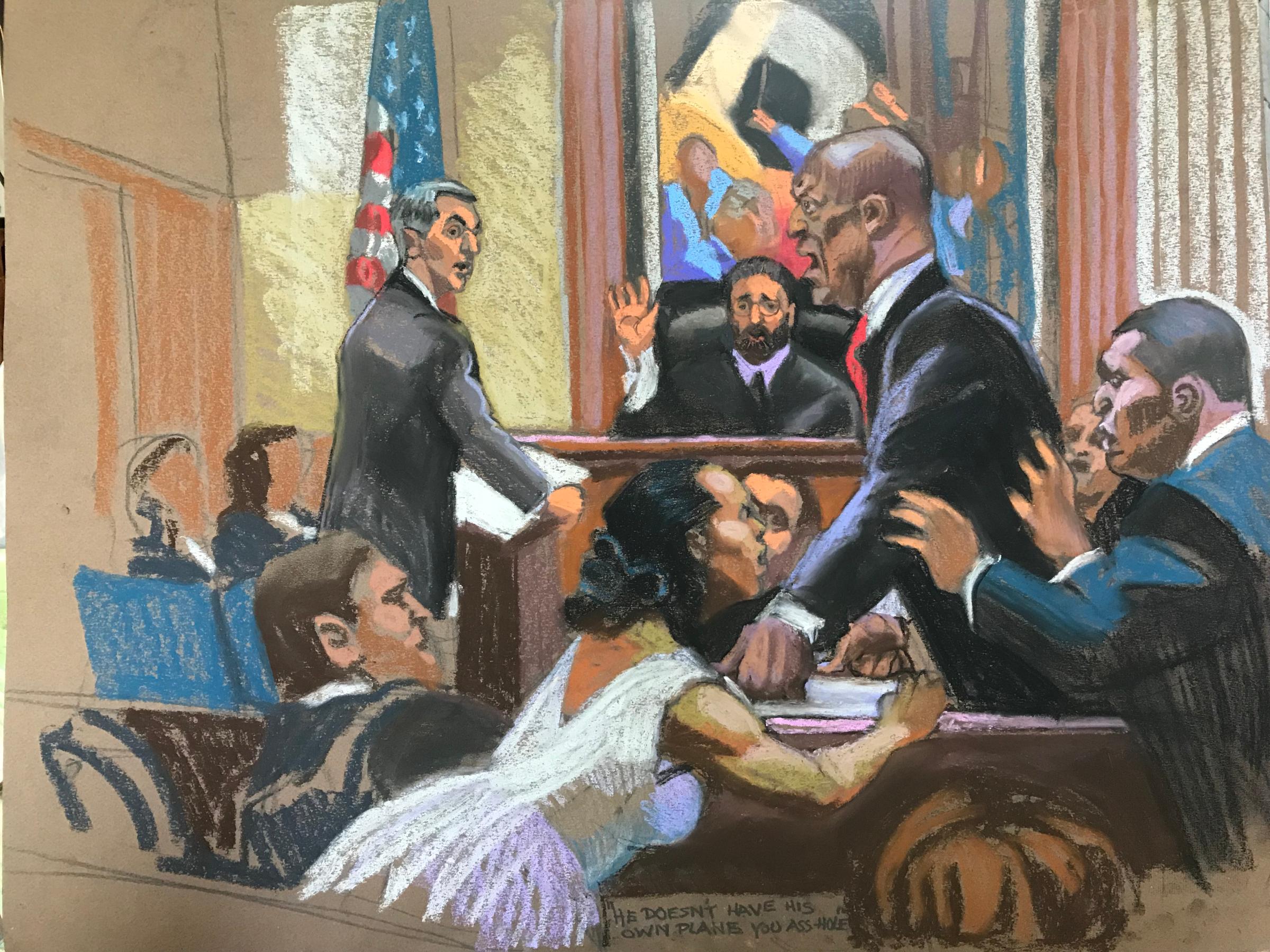

Courtroom sketch artists toe a line of talent, speed, accuracy and precision, as they often serve as the only individuals who can see what happens in some of the most high-profile court cases across the country. Their jobs have changed drastically recently as officials tweak the rules around when cameras can come into the courtroom and as the 24/7 news cycle creates tighter deadlines. All the while, these artists often create these sketches while squeezed into courtrooms, sometimes sitting behind pillars, using binoculars and, in Cornell’s case, shifting in their seats to see the central figures hidden behind bulky court marshals.

“You couldn’t draw under worse circumstances; that’s the truth,” Cornell said.

“If you can’t do this job hanging by your heels from the rafters, then you don’t belong out there.”

Other courtroom sketch artists who spoke with TIME detailed similar deadline pressures as well as difficulties they face staying on their toes as emotional testimonies and dramatic moments create vivid images that require quick thinking and even faster (and accurate) drawings.

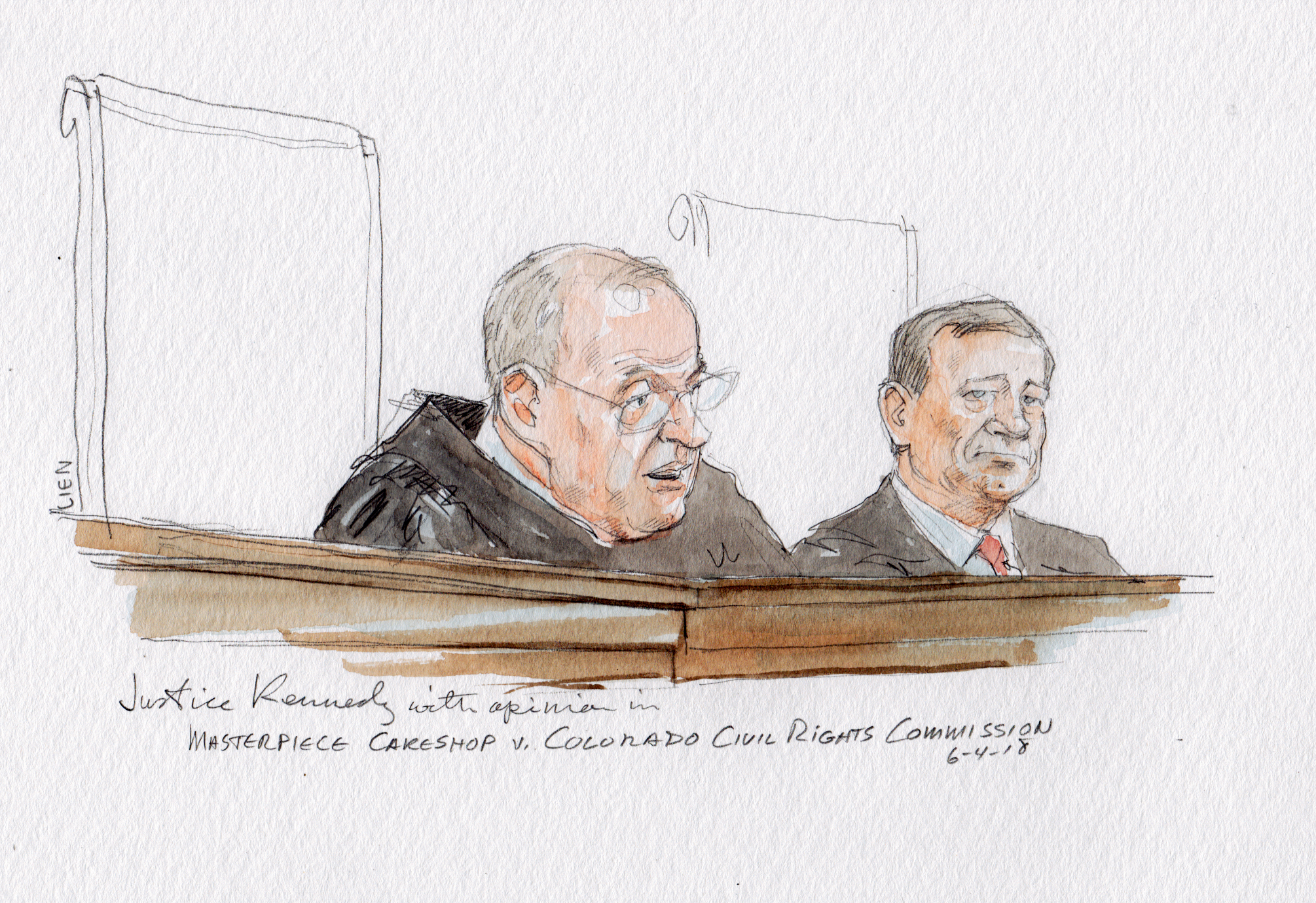

“The deadlines are just crazy now,” said Arthur Lien, a D.C.-based courtroom sketch artist with decades of experience who primarily covers the Supreme Court. “It’s instantaneous.”

Sometimes, artists compete with photographers when judges allow cameras in the courtroom — like last week in New York, when artists and photographers were there to capture Weinstein’s first courtroom appearance. Currently, “a judge may authorize broadcasting, televising, recording, or taking photographs in the courtroom and in adjacent areas during investigative, naturalization, or ceremonial proceedings,” according to federal policy on allowing cameras in the courtroom in the United States. Judges, Supreme Court justices and politicians have weighed in on the debate over cameras being used in court. Those who want courts to allow them often say they would help with transparency, and those who oppose them say they could skew procedures and allow news organizations to show moments out of context, among other arguments.

But so long as cameras stay out of the courtrooms, these sketch artists still have jobs.

In their decades of work, the artists who spoke to TIME have witnessed historic moments, dramatic testimonials and horrific realities that still stick with them today. Just a few months ago, Cornell witnessed a Cosby accuser break down in court during her testimony and then, in a rare move, turn her attention to Cosby himself and speak to him directly. “You could’ve heard a pin drop in the room,” Cornell said.

Jane Rosenberg, a courtroom sketch artist who began her career in 1980, still remembers the mid-1990s trial when Susan Smith was convicted of of two counts of murder after she strapped her two sons in her car and let it roll into a lake. At the time, Rosenberg recalled that she had a child of the same age. There was also the more recent trial of a former nanny who killed two small children in their Upper West Side apartment in New York City.

“Over those 38 years, there were a few times I cried. It’s very hard to draw with tears in my eyes,” Rosenberg, who has also recently sketched Weinstein in his court appearances and Anthony Weiner in his Sept. 2017 sentencing, said. “So I try to stay neutral and keep working.”

Outside of the courtroom, Rosenberg’s art focuses on happier, more idyllic scenes. Her pieces capture snow surrounding Bethesda Fountain in Central Park, blooming flowers, bright bakeries and colorful sunsets. “The courtroom life is all sad,” she said. “It’s just horrific things. Nobody’s happy in a courtroom.”

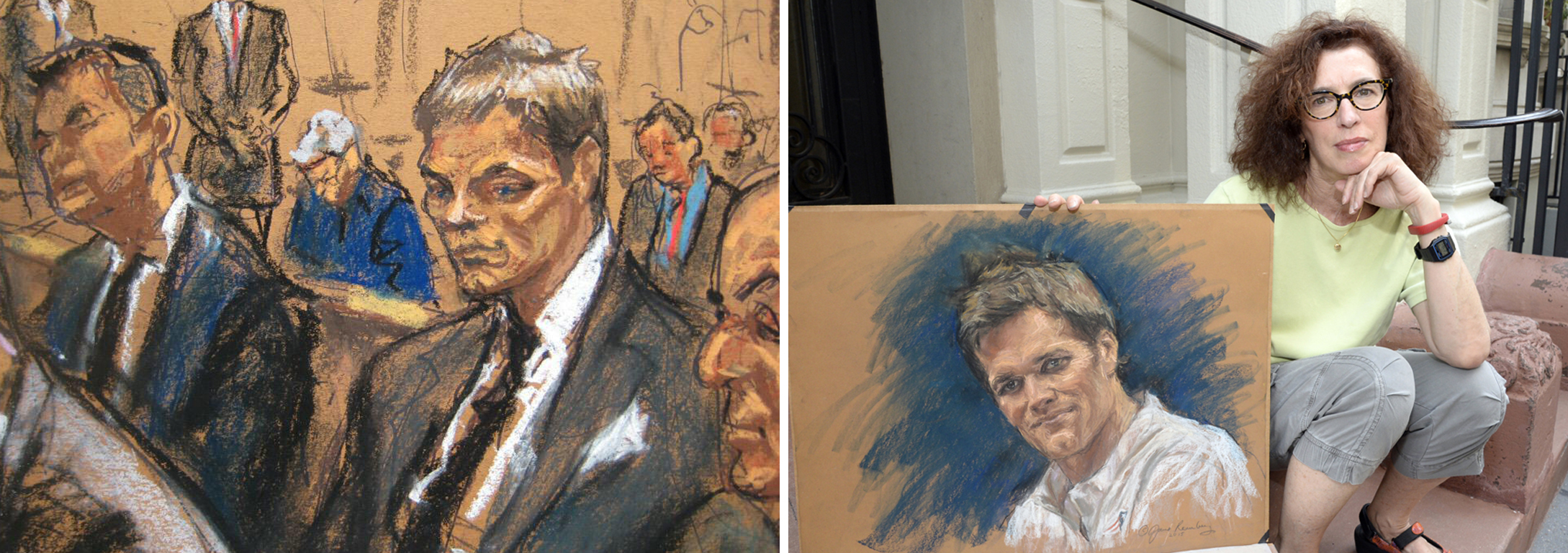

On top of that, when these artists depict famous figures, their sketches can also come with a slew of scrutiny. Rosenberg experienced that first hand when she drew New England Patriots star Tom Brady when he appeared in court amid the Deflategate scandal in 2015. Her sketch went viral online, and she later drew another portrait of him with the same materials, depicting him with softer features than her original drawing.

“Everybody in the world is an art critic now,” Rosenberg said, referring to the impact of social media and the 24/7 news cycle. “That’s what’s different.”

Cornell saw some criticism, too, when she drew actress Uma Thurman in a 2008 court appearance, she said. And back in 1980, before social media could make a sketch go viral for one reason or another, Lien said he felt the pressure for intense accuracy as well. He was tasked with sketching former President Richard Nixon who, at the time, was testifying on behalf of Mark Felt. (Felt, ironically, was later revealed as Deep Throat.) “There was this feeling of, ‘Gosh, you have to get Nixon just right,’” he said. “I know one artist there basically lost her job because she was not having a good day.”

When they’re not competing with each other or the other cameras in the room, what many of these courtroom sketch artists share is the ability to filter these distractions — both in the courtroom and out of it — and get the job done.

“I’m really just there to be a good antenna. I don’t put any spin on it. I just try to make the drawing feel like them and what we’re seeing and what we’re witnessing,” Cornell said. “That’s what we’re there for. To tell the story — and to tell the whole thing.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How Donald Trump Won

- The Best Inventions of 2024

- Why Sleep Is the Key to Living Longer

- Robert Zemeckis Just Wants to Move You

- How to Break 8 Toxic Communication Habits

- Nicola Coughlan Bet on Herself—And Won

- Why Vinegar Is So Good for You

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Contact us at letters@time.com