The following feature is excerpted from LIFE’s special edition Robert F. Kennedy: An American Legacy.

John Kennedy’s death haunted Bobby. He couldn’t sleep and walked around in a trance, plagued by guilt. “He is worried that he has gotten his brother killed and is really psychologically undone for a long period,” says [biographer] Evan Thomas. He feared that the targets he pursued—Castro, the Mob, and others—had exacted a dreadful price. “I thought they’d get one of us,” Kennedy told Edwin Guthman, who worked for him in the Justice Department. “I thought it would be me.”

With her husband’s death, Jackie Kennedy leaned heavily on her brother-in-law. The two made numerous nighttime visits to John’s grave, and they found themselves discussing religion and God. Looking for guidance to make sense of the incomprehensible, Bobby read Shakespeare and other classics, along with the works of the ancient Greeks that Jackie suggested. “I am going to dwell in the pain, and I am going to understand that something terrible has happened,” his daughter Kathleen recalled him saying.

Ethel remembered it as “six months of just blackness.” But after her husband reemerged, he was a different man. As Village Voice writer Jack Newfield observed, Kennedy had a “private, internal change, from rigidity to existential doubt, from coldness to an intuitive sensitivity for sorrow and pain, from one-dimensional competitiveness to fatalism, from football to poetry, from Irish-Catholic Boston’s political clubhouses to the unknown.”

He also inherited John’s legacy. But, still serving as attorney general, he had to work with Lyndon Johnson. Although Johnson promoted John’s policies, in Bobby’s eyes the man was a usurper. “Johnson was the wrong person to inherit the mantle from Bobby’s perspective,” says [historian] Jeff Shesol.

With John gone, Robert Kennedy lost his zeal for leading the Justice Department, and in the fall of 1964 he sought a Senate seat from New York. He also appeared at the Democratic National Convention to speak before a showing of a film about his brother.

For the gathered delegates, the awkward man at the podium had come to represent what they had lost. Following a 22-minute standing ovation, Bobby told the Democrats that when he thought of his brother he thought of words spoken by Shakespeare’s Juliet: “When he shall die / Take him and cut him out in little stars / And he will make the face of heaven so fine / That all the world will be in love with night / And pay no worship to the garish sun.”

After Bobby finished, he found a spot on a fire escape and wept for 15 minutes.

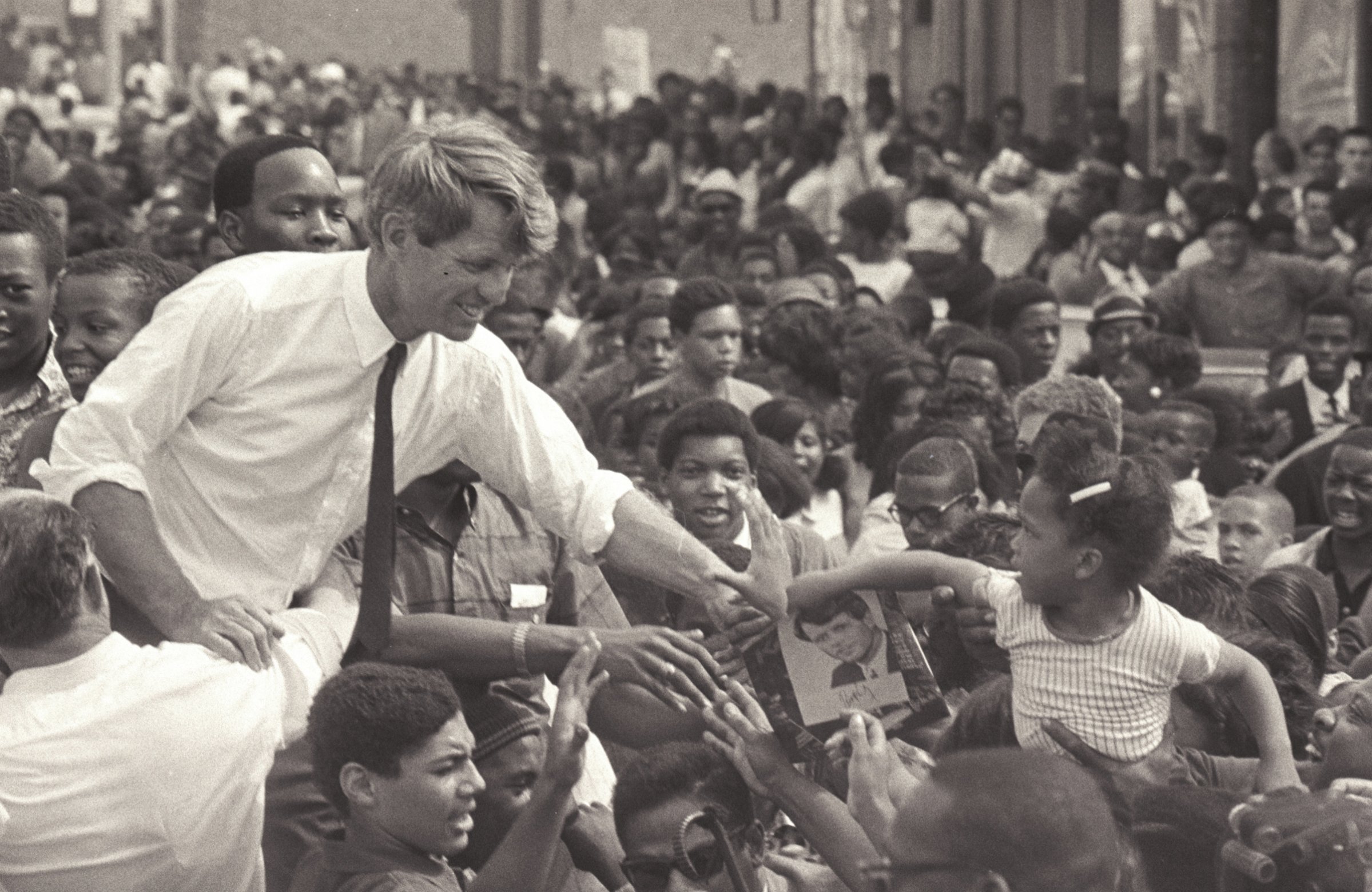

In his race against the incumbent, Republican senator Kenneth Keating, Bobby was called a carpetbagger from Massachusetts and proved to be a flat public speaker. But none of that seemed to matter. Crowds turned out to see him, driving him to compare himself to the Beatles. He had, though, no illusions about the source of his popularity, telling Edwin Guthman that he knew the crowds were really there because of John. “They’re for him. They’re not for me,” he acknowledged.

Bobby won.

Soon after, Canada named its tallest unconquered peak in honor of his brother. The National Geographic Society sought to put together an expedition to scale the mountain, located in the Yukon Territory. Though he had never climbed before and disliked heights, Kennedy agreed to take part. When asked by his guide, Jim Whittaker—the first American to scale Mount Everest—how he prepared for the climb, Bobby said, by “running up and down the stairs and practicing hollering ‘Help!’”

The expedition set off on the 13,900-foot ascent, and the climbers slept in tents and endured blizzard conditions. Despite his lack of training, Bobby relentlessly pushed ahead, reciting poetry to pace himself, and took to heart his mother’s advice: “Don’t slip, dear.” As they neared the summit, the team allowed Kennedy to proceed alone.

At the top he set in the snow his family coat of arms, coins bearing John’s face, PT-109 tie clips, and a copy of his brother’s inaugural address. “It was cleansing,” said Ethel. “It gave him the impetus to go on and start again.”

Back in Washington, he got to work. But the Senate proved a bad fit for the brooding legislator. He chafed at being a junior member with little influence. Yet the chamber gave him a bully pulpit from which to inveigh against the ills plaguing the nation. At John’s last cabinet meeting, the President wrote “poverty” a number of times on a piece of paper and circled the word. Bobby had the crumpled paper framed, and he found his own voice in giving voice to the dispossessed. As the nation’s attorney general he had traveled widely across the United States in his quest to understand poverty, making his way to Chicago slums and Native American reservations in North Dakota. Now he started heading to such countries as Poland, Peru and Argentina to get a better sense of international affairs.

Kennedy’s favorite song was “The Battle Hymn of the Republic” and, like some anointed soldier of the Lord, he flew to South Africa in June 1966. Invited by the anti-apartheid National Union of South African Students, he came to deliver the annual Day of Affirmation speech.

The land was under the yoke of apartheid, and Bobby and Ethel toured Johannesburg, Cape Town, Durban and Pretoria. He met with Nobel Peace Prize winner Chief Albert Luthuli, the president of the outlawed African National Congress. He walked down streets shaking the hands of black servants, and crowds swarmed to gaze at him. He delivered five speeches, the most famous at the University of Cape Town. “Each time a man stands up for an ideal, or acts to improve the lot of others, or strikes out against injustice, he sends forth a tiny ripple of hope,” he said, “and crossing each other from a million different centers of energy and daring, those ripples build a current that can sweep down the mightiest walls of oppression and resistance.”

Change, Bobby believed, was possible. A fan of the song “The Impossible Dream” from the musical Man of La Mancha, he took to heart the idea of tilting against windmills. He read the work of Ralph Waldo Emerson and embraced the idea of the dignity of work. In Delano, Calif., he met with Cesar Chavez, who was trying to organize farm workers. In Brooklyn’s Bedford Stuyvesant neighborhood he launched a community development organization. Hungry children especially troubled him. After returning from the Mississippi Delta, he expressed to friend Amanda Burden the feeling that, given what he had seen, all the work he had done in his life amounted to nothing.

Bobby’s pained and looming presence haunted Johnson. The President feared Kennedy. By the mid-1960s the war in Vietnam had started consuming the nation. Kennedy, who during his brother’s administration saw the slow growth of U.S. presence there, had long had concerns about Johnson’s military buildup, which took the nation’s commitment from 23,300 troops in 1964 to 485,000 in 1967.

Bobby felt he had no other choice but to speak out in opposition to President Johnson’s course. He took to the Senate floor and called for an end to the bombing of North Vietnam and the start of peace talks with Hanoi. “I can testify that if fault is to be found or responsibility assessed,” he said, “there is enough to go around for all—including myself.”

Many of his advisers and friends wanted him to do more than just object. They wanted him to seek the presidency.

Ethel even had the children hang a banner reading “Run, Bobby, Run” outside the house. When John won in 1960, he had given Bobby a cigarette case inscribed, “When I’m through, how about you?” But the Senator feared being accused of ambition and envy, and he didn’t want to run until and unless the time was ripe.

Read more in LIFE’s special edition Robert F. Kennedy: An American Legacy.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How the Economy is Doing in the Swing States

- Harris Battles For the Bro Vote

- Our Guide to Voting in the 2024 Election

- Mel Robbins Will Make You Do It

- Why Vinegar Is So Good for You

- You Don’t Have to Dread the End of Daylight Saving

- The 20 Best Halloween TV Episodes of All Time

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Contact us at letters@time.com