It’s 1 a.m. on a Saturday, and Dr. Abdul El-Sayed is asking for votes at a hookah bar in Dearborn, Mich. Making the rounds with the 20-and-30-somethings out for the night, he’s wearing a sharp suit and trailed by a young aide with a stack of voter-registration forms. When the waitress brings El-Sayed his order, he points at her and says, “August 7th?”

The date of the Michigan gubernatorial primary is in her calendar already, she says. She’ll be voting for him. El-Sayed grins. “One day you’ll be able to say you quenched the Governor’s thirst for an avocado smoothie,” he says.

El-Sayed, 33, is the former Detroit health commissioner and one of three candidates running for the Democratic nomination in Michigan’s gubernatorial race. He’s up against Gretchen Whitmer, a veteran legislator who led Democrats in the state Senate, and Shri Thanedar, a wealthy chemical-testing entrepreneur, in a race that will help shape the future of the Democratic Party in a state that voted first for Bernie Sanders and then for Donald Trump in 2016.

The primary offers a glimpse at how the party can chart a path forward in a former Democratic stronghold that flipped unexpectedly to Trump. Michigan is one of most anti-establishment states in the nation, but the race is a window into several national trends. The outcome of the midterms depend on the Democrats’ ability to field compelling candidates who can speak to both voters of color and working-class whites. Women are running for office in unprecedented numbers, progressives are trying to capture the insurgent energy of Sanders’ campaign, and political outsiders are jumping into the arena. All these themes are colliding in a Michigan primary that features a young Muslim progressive; a battle-tested female politician and an Indian-born business mogul.

The race is playing out in a state whose residents have developed a justifiable mistrust of government, and where government transparency and accountability is the worst in the nation, according to a 2015 ranking from the Center for Public Integrity. Michigan is a state that allowed thousands of Flint children to drink tainted water, where Larry Nassar was able to molest hundreds of girls while on a state-university payroll, where a Republican legislature passed a right-to-work law in a historic union stronghold. The battle for the Democratic nomination isn’t just about who will get to represent the party on the ballot in the fall; it’s about who can restore Michiganders’ faith in the system again.

On policy, there’s not much daylight between the Democratic candidates on the main issues in the race. All the candidates support a $15 minimum wage, oppose a pipeline being built under the Great Lakes, promise to clean up the drinking water and want to get rid of Michigan’s “right-to-work” law that crippled organized labor in the state. As a result, the race may boil down to style more than substance.

Thanedar, an Indian immigrant and self-made millionaire, has surged in early polls after spending $6 million of his own money on his campaign, including more than $1 million on TV ads (the other two candidates haven’t invested heavily in TV advertising yet.) He says he supports single-payer health care and refuses corporate donations, and his ads call him the “most progressive Democrat” in the race. Thanedar has billed himself as a “fiscally savvy Bernie,” and shrugs off his opponents’ allegations that he’s a millionaire trying to buy the race. “The fact that I am a person of wealth should not be held against me,” Thanedar says. “A person who is successful in running a business can also be very progressive.”

While the ads have raised his profile, Thanedar’s campaign has also run into obstacles. He’s being sued in federal court for business fraud after allegedly inflating the value of his company before it was sold in 2016 (Thanedar says this was “just a business dispute”) and he’s come under fire for alleged mistreatment of dogs and monkeys who were reportedly abandoned at one of his chemical-testing facilities. Opponents have questioned his political history: he donated to John McCain’s campaign in 2008, attended a political rally for GOP Senator Marco Rubio in 2016 and allegedly considered running for Governor as a Republican, according to consultants he met with.

Which is part of the reason why Whitmer is still widely considered the Democratic frontrunner. The five-term state legislator been endorsed by Emily’s List, the Michigan AFL-CIO, the United Auto Workers and Detroit mayor Mike Duggan. Whitmer’s powerful testimony about her own sexual assault during a 2013 speech could help her in a year when women candidates have the wind at their backs thanks in part to the power of the #MeToo movement.

“I have been the leader of the Resistance the whole time I was in public life,” Whitmer says, pointing to her years heading a Democratic minority in the state Senate. “I’ve been known for speaking truth to power and taking on people in power when they’re wrong.”

Whitmer is running on kitchen-table issues like jobs and fixing Michigan’s roads (she called her infrastructure tour “Fix the Damn Roads.”) But she’s also the only candidate who has stopped short of adopting the Sanders-style progressivism helped him win the Michigan primary in 2016: she hasn’t rejected money from corporate PACs (Blue Cross Blue Shield raised money for her campaign) and she’s the only candidate who isn’t calling for single-payer health care (although Whitmer takes credit for putting together the Senate votes to pass Michigan’s Medicaid expansion bill, which gave health coverage to 680,000 people.) She also lags behind her opponents in name recognition.

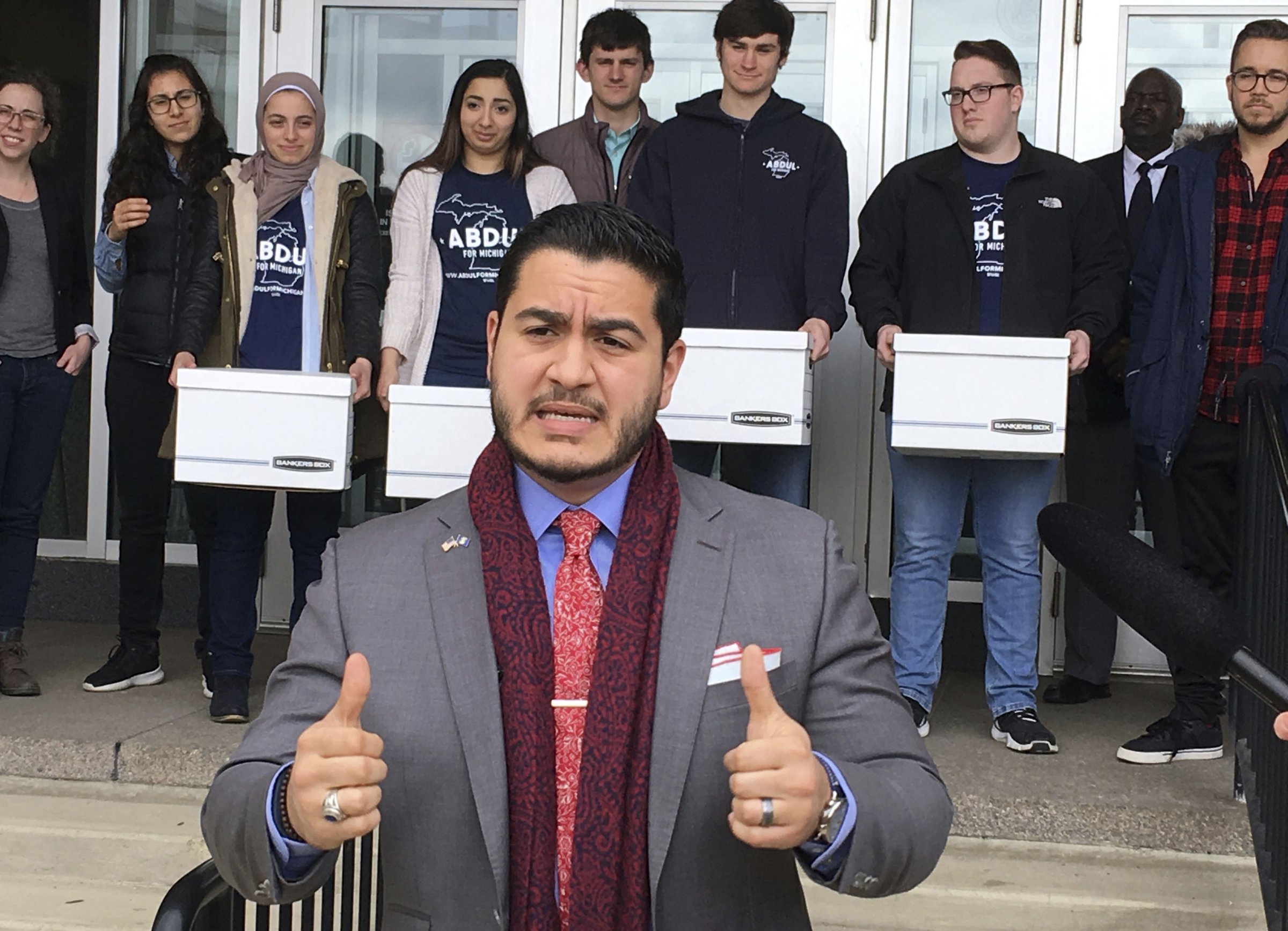

That leaves El-Sayed, the underdog. He’s borrowing the Sanders playbook, from his policy positions (free college, marijuana legalization) to a young, digital-savvy staff led by several former Sanders staffers. El-Sayed’s only political experience is as health commissioner: under his watch, the city tested the water at every Detroit school and daycare, blocked a major polluter from increasing its emissions, and provided free eyeglasses to any Detroit kid who needed them. He also clashed with Detroit Mayor Mike Duggan over water shutoffs and housing demolition. Duggan ended up endorsing Whitmer.

El-Sayed knows he has an uphill battle. He’s “a little young, a little brown, a little Muslim,” as he puts it, and he’s currently polling at around 6%. But he also boasts an enthusiastic grassroots base made of mostly young volunteers, a fresh face, and oratorical chops that spur comparisons to a young Barack Obama (although El-Sayed disavows the comparison.) “I don’t have all the right friends, I don’t have all the right money that I’ve made in questionable ways,” El-Sayed tells an association of black voters in Detroit. “What I do have is a message.”

Even some Trump voters see the appeal. “A fresh face shakes off the political establishment,” says Sean Elkhatib, 28, who voted for Trump in 2016 (he calls it a “chaos” vote) but now plans to vote for El-Sayed.

Whatever happens in August, the Michigan primary is a test of whether Democrats can engage the voters that turned out to vote for Sanders in the 2016 primary but then voted for Trump or stayed home in the general election. And reaching those voters, while keeping the ones who showed up for Clinton, will be a key to winning the midterms.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Charlotte Alter/Dearborn at charlotte.alter@time.com