It sounded like a scandal. In a series of late-May tweets, President Trump alleged that the Obama Administration had placed a spy in his 2016 campaign for political purposes. “This is bigger than Watergate!” he wrote. But “SPYGATE,” as Trump dubbed it, was not exactly what he said it was. The FBI had reportedly deployed an informant to covertly question low-level members of Trump’s circle who had been contacted by Russian operatives. The goal, according to Democratic and Republican members of Congress who have seen the intelligence, was to figure out what Moscow was up to, not to infiltrate Trump’s campaign.

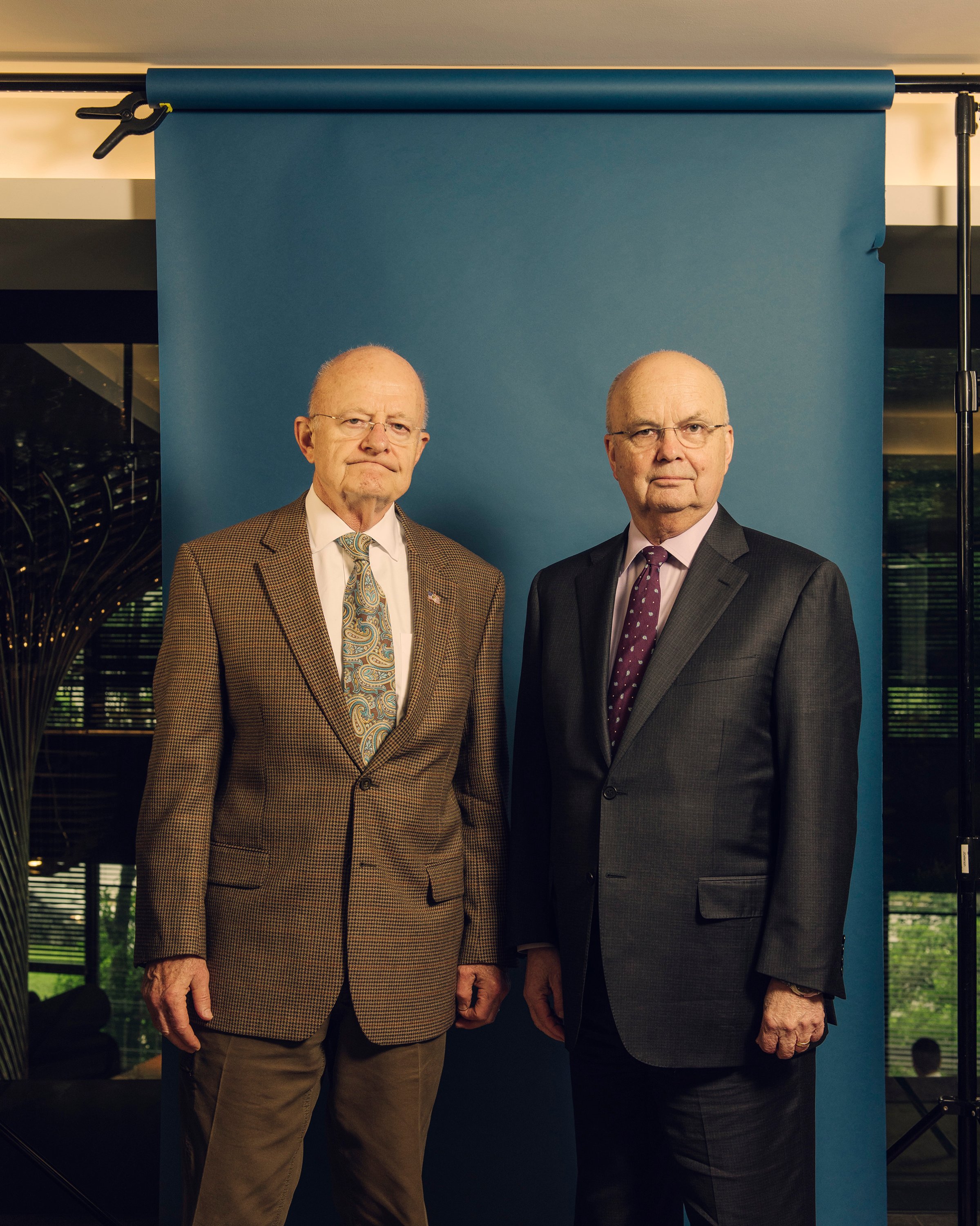

To James Clapper and Michael Hayden, two long-serving, retired leaders of the U.S. intelligence community, Trump’s tirade was just the latest in a string of politically motivated attacks on America’s spies. “[Trump] is undercutting the validity of institutions on which we’re going to have to rely long after he’s left office,” says Hayden, who led the Central Intelligence Agency from 2006 to 2009 and the National Security Agency from 1999 to 2005. Trump “is constitutionally illiterate [and] a real test of our institutions and values, and the country’s resilience,” says Clapper, who led the Defense Intelligence Agency from 1991 to 1995 and was Director of National Intelligence from 2010 to 2017.

That is unusually tough talk from two former Republican appointees. But Hayden and Clapper say the schism between the President and the U.S. intelligence community is really about the breakdown of trust between the government and the governed. Over the course of their careers, they have watched Americans’ faith in their government collapse. In 1964, 77% of Americans trusted the federal government most or all of the time, according to the Pew Research Center. As of December 2017, that number was 18%, nearing an all-time low.

Now both men have written books arguing that Trump is tapping this distrust to advance his own power, threatening the stability of the Republic in the process. They worry that the steps taken after Watergate to restore public trust in government are collapsing. Ultimately, they fear that the consensus that holds the nation together–objective truth–is breaking down. That, they say, has been a precursor to government collapse, civil war and dictatorship in other countries, and they worry the same thing can happen here. “That’s why this really scares me,” says Hayden.

Clapper and Hayden are quick to say that Trump is more a symptom of America’s dysfunction than its cause. But there is a danger in this kind of talk. Hearing the Republic is under attack from the President can suggest that drastic action is called for, which can itself undermine the institutions of government. And exaggerated threats have been just as damaging to public faith in the intelligence community as threats that went undetected. To talk about it, the men met TIME at the Watergate complex, where a 1972 break-in spawned the scandal that redefined the terms of governance.

Neither man is tailor-made for the job of restoring faith in truth and government. For starters, some spies lie. And it was the discovery that America’s intelligence services had been exploiting secrets for something other than the national good that fueled the crisis after Vietnam and Watergate. Congressional investigators in the 1970s found that the CIA, NSA and FBI had been meddling in politics and breaking the law to protect the interests of their agencies and preferred political bosses, not the American people.

In response, Congress created special committees to oversee the work of the intelligence community. With the new constraints in place, Hayden says, “we took it as an article of faith that if we followed the [new rules], we are doing things that are legitimate within American political culture.”

The post-Watergate measures held up for decades. There were crises, including the intelligence community’s failure to spot the 9/11 terrorists’ plot, the faulty intelligence that contributed to the decision to go to war in Iraq and the 2013 revelations by Edward Snowden of the government’s electronic-surveillance programs. But even as faith in the federal government declined, trust in the intelligence agencies remained relatively high. In 2015, faith in the CIA was still about 60%, according to Pew, and in the NSA about 52%.

A year later, public confidence in the CIA had plummeted to 33%, according to an NBC/Wall Street Journal poll. Congress and the spies point fingers at each other over who is to blame. Hayden says the outcry that followed Snowden’s revelations showed that public support for American spies was already eroding. “What I discovered,” Hayden says, “is that the post-Watergate structure for gaining legitimacy from the American people was no longer adequate.” The programs Snowden revealed had been approved by the congressional committees, Clapper and Hayden agree. What had changed, says Hayden, was “a growing unwillingness of the American people to outsource this oversight and validation to their elected representatives.” Americans, he says, no longer trusted Congress to keep the spies in check.

Congressional critics see things differently. They argue that the extraordinary measures the CIA, NSA and others took after 9/11 to fight terrorism included evading congressional oversight, and so broke the post-Watergate compact. And they say both Clapper and Hayden bear some of the blame for the resulting loss of faith. In September 2006, Hayden first testified to the congressional oversight committees about the CIA’s “enhanced interrogation” program. A multiyear report by the Senate Intelligence Committee later concluded that the CIA had engaged in widespread torture, which is illegal, and that Hayden had misled the committees. Clapper, for his part, has been accused by Republicans and Democrats of lying about the extent of NSA surveillance under the Patriot Act.

Hayden says he should be given credit for the desire to bring the interrogation program before Congress. “I was doing the best I can with a complex program that I didn’t start or run,” he says. Clapper says he misunderstood a Senator’s question during testimony. “It was at the end of a 2½-hour threat hearing,” he says. “So, yes, I regret that. But it was a mistake, not a lie. There’s a big difference.”

What is clear in retrospect is that by 2016, Americans’ faith in their spies was shaky at best. Hayden and Clapper see that as the result of a larger crisis in America. Clapper argues in his book Facts and Fears that the expansion of economic inequality after the Cold War fueled what he calls “unpredictable instability” for many Americans. The financial crisis that began in 2007, he says, further drove resentment and distrust. In The Assault on Intelligence, Hayden says a combination of increased political polarization, fueled by the self-sorting world of the Internet, is what has brought us to this point.

But it was the Russian operation against the 2016 election that revealed the extent of the problem, Clapper and Hayden agree. “The Russians, to their credit, capitalized on the polarization and the schisms and the tribalisms in this country,” says Clapper. By flooding social media with divisive propaganda and meddling with U.S. state and local election systems, the Russians undermined faith in the democratic process. “To me, the most damaging and threatening thing that they do is to cast doubt on what’s truth,” Clapper says. Moscow wins, he says, when people ask: “Is truth even knowable?”

Trump is doing the same thing, the former spy chiefs say. “We live in a post-truth environment,” says Hayden, “and he quite cleverly identified that as a candidate, and now he worsens it as President by some of what he does and a lot of what he says.” Trump’s rallies, says Clapper, “are really scary to me, because he goes so far afield of the truth.”

The two men are particularly aware of how Trump has undermined the intelligence community. As the Russian operation came to light during the campaign, Trump mercilessly attacked American spies and called into question their warnings. When it became clear that Russia had actively tried to help Trump win the election, he compared U.S. intelligence officials to Nazis. “He has besmirched the Intelligence community and the FBI–pillars of our country–and deliberately incited many Americans to lose faith and confidence in them,” Clapper writes.

More worrying, Clapper and Hayden say, is how Trump is undermining the very system of constraints that was instituted after Watergate to prevent abuse by the intelligence services. Among his most florid attacks was the false allegation that the Obama Administration illegally wiretapped Trump Tower during the election. In fact, the FBI legally obtained eavesdropping warrants from a special court that requires evidence that the target is acting on behalf of a foreign power.

The same goes for Trump’s latest “spygate” allegations. According to both Republicans and Democrats who have seen the intelligence on the matter, including House Republican Trey Gowdy of South Carolina, the spies complied with all the internal and external rules controlling how and when they can covertly investigate a political campaign. By undermining intelligence agencies that are complying with the rules, Trump is calling into question the rules themselves. “What we have is a President,” says Hayden, “attacking and undercutting the validity of institutions.”

Why would Trump make such a sustained, frontal assault on the legitimacy of the government? Perhaps because his own legitimacy is at stake. In his book, Clapper makes the provocative assertion that the Russian operation helped determine the outcome of the election. “Of course the Russian efforts affected the outcome. Surprising even themselves, they swung the election to a Trump win. To conclude otherwise stretches logic, common sense, and credulity to the breaking point,” Clapper writes. “Less than eighty thousand votes in three key states swung the election. I have no doubt that more votes than that were influenced by this massive effort by the Russians.”

Whatever Trump’s reason for attacking America’s government, Hayden says the possible results are ominous. “[It] is not that civil war or societal collapse is necessarily imminent or inevitable here in America, but that the structures, processes and attitudes we rely on to prevent those kinds of occurrences are under stress,” Hayden writes. “I am saying that with full knowledge of other crises we have (successfully) faced. But there most often we argued over the values to be applied to objective reality … not the existence or the relevance of objective reality itself.”

There is little question that Trump’s presidency has crippled the critical relationship between U.S. intelligence agencies and the congressional committees that oversee them. The arrangement hinges on both sides’ operating in good faith and above politics. In April, Republicans on the House Intelligence Committee published the findings of its investigation into Russian interference in the 2016 election. The report implicitly rejected the consensus among U.S. intelligence agencies that Moscow’s efforts were designed to boost Trump. Democrats on the panel panned the report’s conclusions and accused their GOP colleagues of abetting Trump’s effort to discredit investigators, including special counsel Robert Mueller. The distrust and partisan acrimony will be hard to repair.

The question is what to do now. The first thing, says Hayden, is to avoid self-inflicted wounds. Institutions that are designed to guard the public interest against the passing wiles of politicians “very often are tempted to break their own norms in pushing back against the norm-busting President,” says Hayden. That “is a really serious problem,” he argues, because it further erodes public faith in government.

Clapper prescribes more candor. After 9/11 and in the years before Trump’s election, the intelligence community was “not being sufficiently transparent and open,” he says. “So, lesson learned. Early communication and more transparency.”

America’s institutions have been tested before, and each time they have proved resilient. Despite the fears cataloged in their books, both Clapper and Hayden expect the pillars of U.S. democracy to survive the attacks by the President. One way or another, they will outlast Trump.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com