With LGBTQ Pride Month beginning June 1 — a month chosen to honor the history of activism epitomized by the Stonewall Riots of June 1969 — celebrants around the world will be getting ready for parades and other tributes. Symbols such as the rainbow flag and the pink triangle will abound; for example, Nike has announced a new line of LGBTQ history-themed sneakers, including two that boast pink triangles.

The brightly colored symbol is now often worn proudly, but it was born from a dark period in LGBTQ history and world history.

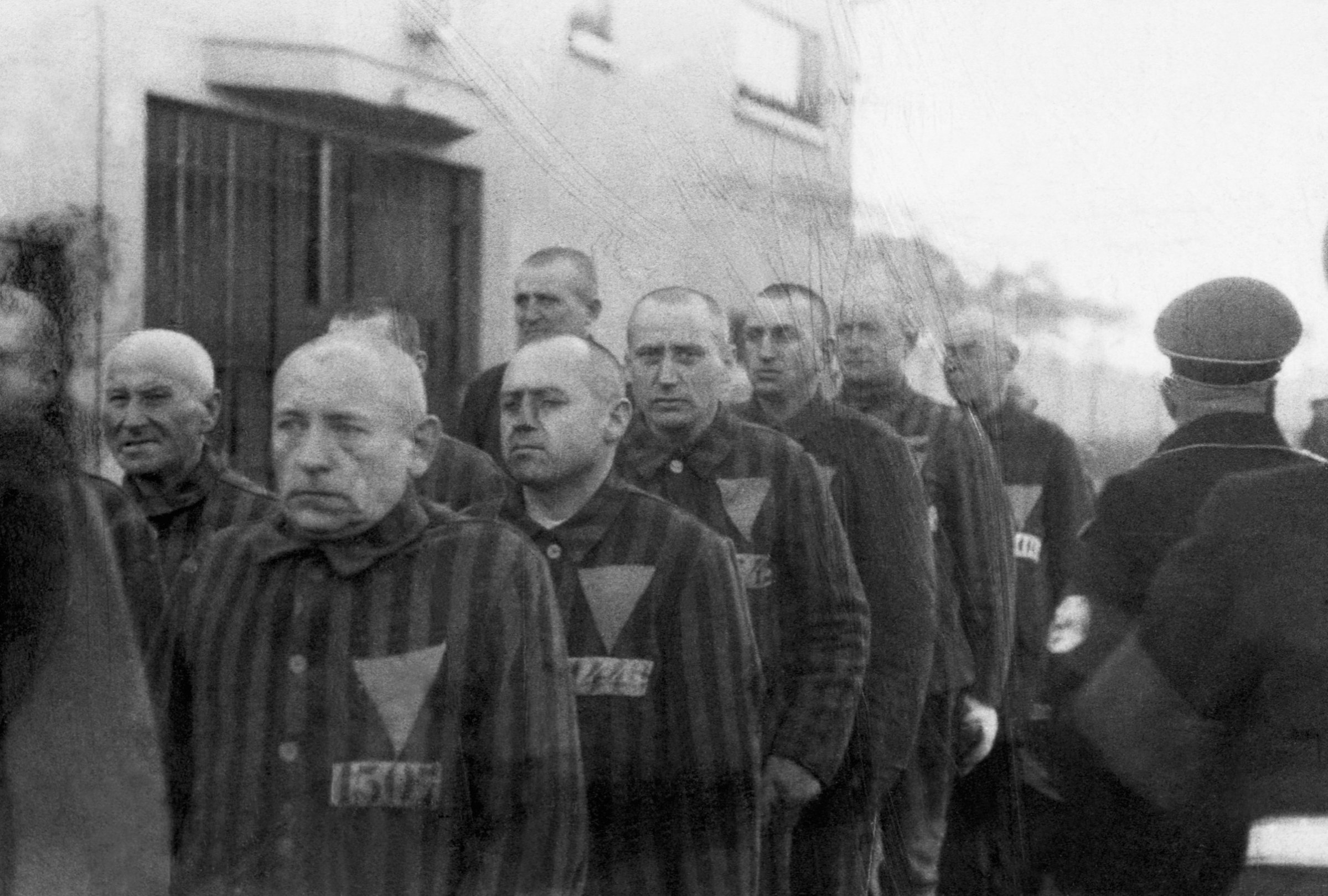

Just as the Nazis forced Jewish people to wear a yellow Star of David, they forced people they labeled as gay to wear inverted pink triangles (or ‘die Rosa-Winkel’). Those thus branded were treated as “the lowest of the low in the camp hierarchy,” as one scholar put it.

The roots of the Nazi persecution of gay people are deep. Since German unification in 1871, a section of the country’s criminal law widely known as “paragraph 175” had said that men who engaged in acts of “unnatural indecency” could go to jail. In 1877, the German Supreme Court of Justice clarified that to mean evidence of an “intercourse-like act.” But the law was only enforced sporadically. And the fact that it was almost impossible to convict anyone unless he confessed to such a crime in court meant that police just kept a watchful eye on gay bars and events, and Germany ended up becoming home to a vibrant gay community. Historian Robert Beachy argues that, ironically, the law spurred scientific interest in the study of sexual preferences, and that research tended to encourage a more scientific understanding of human sexuality, which further allowed the idea of gay rights to flourish.

More from TIME

According to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (USHMM), that changed when the Nazis came into power in the 1930s. Hitler saw gay men as a threat to his campaign to purify Germany, especially because their partnerships could not bear children who would grow the Aryan race he wanted to cultivate. During that period, gay-friendly bars and clubs started being shut down, authorities burned the books at a major research institution devoted to the study of sexuality, and gay fraternal organizations were shuttered. These efforts only increased after the Night of the Long Knives, the 1934 purge of Nazi leaders who were accused of trying to overthrow Hitler; they included Storm Troopers leader Ernst Röhm, whom the SS murdered, later citing his homosexuality as justification for his murder. A Nazi revision of the 1871 law took effect in September of 1935, outlawing anything as simple as men looking at or touching one another in a sexually suggestive way, and enabled authorities to arrest people even if they had only heard rumors that people had been engaging in such behavior. (Lesbians, however, didn’t face the same criminal penalties.) The Gestapo began to keep “pink lists” of violators.

Between 1933 and 1945, by the USHMM’s count, an estimated 100,000 men were arrested for violating this law, and about half went to prison. It’s thought that somewhere between 5,000 and 15,000 men were sent to concentration camps for reasons related to sexuality, but exactly how many died in them may never be known, between the scant documentation that survived and the sense of shame that kept many survivors silent for years after their ordeal.

From the few survivors and prison guards who have shared their stories, it’s been learned that those sent to concentration camps were segregated, for fear that their sexual preference was contagious. Many were castrated. Some were used as guinea pigs in various medical experiments to find a cure for typhus fever and a cure for homosexuality, the latter of which led the SS to inject them with testosterone to see if it would make them straight. At the same time, some Kapos (prisoners selected by the SS to keep fellow prisoners in line) are said to have demanded sexual favors from prisoners, who were known as “doll boys,” in exchange for extra food or protection from hard labor.

Yet in the post-war years, fear of arrest and imprisonment didn’t go away. The Nazi law stayed in place until a 1969 West German law decriminalized gay relationships among men over 21. As one of the USHMM’s curators has pointed out, even as the Allied powers carefully worked to scrub Nazism from Germany, they left that part alone — perhaps because they had anti-gay and anti-sodomy laws of their own. Paragraph 175 wasn’t repealed until 1994.

As the gay liberation movement grew in America in the ’70s and the ’80s, so did awareness of the persecution of gays during the Holocaust, as books and data about period started being published.

Former “doll boy” Heinz Heger’s 1972 memoir The Men With The Pink Triangle described SS guards torturing prisoners by dipping their testicles in hot water and sodomizing them with broomsticks. Data on these victims started to be cited in 1977, after a statistical analysis by sociologist Rudiger Lautmann of Bremen University claimed that as many as 60% of the gay men sent concentration camps may have have died. The first reference to pink triangles in TIME also appeared that year, in a story about gay-rights activists in Miami who attached the symbols to their clothes as a show of solidarity while protesting a vote to repeal a law protecting gay people from housing discrimination. When the magazine noted that the symbol was “reminiscent” of Nazi-era yellow stars, a reader wrote in to note that they were in fact analogous, not “reminiscent,” as both the star and the triangle were real artifacts of that time. “Gay people wear the pink triangle today as a reminder of the past and a pledge that history will not repeat itself,” he added.

And while the Miami effort did not succeed, the activists did succeed in bringing national attention to the way they had reclaimed the pink triangle as a symbol of solidarity. In 1979, Martin Sherman’s play Bent, inspired by Heger’s memoir, opened on Broadway; in the play, one of the characters trades in his pink triangle for a yellow star, “which gives him preferential treatment over the homosexuals,” as TIME’s review put it. The magazine called the play “audacious theater” and a “gritty, powerful and compassionate drama.” Sherman later said that he had also based the play on research by Holocaust scholar Richard Plant, who was having trouble finding a publisher who would turn it into a book, as the topic was still considered taboo. It was later published as The Pink Triangle: The Nazi War Against Homosexuals.

By that time, the gay community was facing a very different threat: HIV and AIDS. The activists who formed the organization ACT-UP to raise awareness about this public health crisis decided to use the pink triangle as a symbol of their campaign and alluded to its history when they declared, in their manifesto, that “silence about the oppression and annihilation of gay people, then and now, must be broken as a matter of our survival.” Avram Finkelstein is credited with designing the campaign’s pink triangle — which is right-side up, instead of the Nazi-era upside-down pink triangle — after conservative pundit William F. Buckley suggested that HIV/AIDS patients get tattoos to warn partners in a 1986 New York Times op-ed. Earlier this year, Finkelstein said that the op-ed was a “galvanizing moment,” at a time when there was “public discussion of putting gay men into concentration camps to keep the epidemic from spreading.” This bolder stance required a more boldly colored triangle. He explained that the triangle in the middle of the campaign’s signature “Silence=Death” poster was fuchsia instead of pale pink, as a nod to the punk movement’s adoption of the “New Wave” color. (He said the background of the poster is black because “everyone in lower Manhattan wore black.”)

More recently, pink triangles have been visible during gay rights demonstrations worldwide that were sparked by reports that gay men were being persecuted in Chechnya. For example, outside of the Russian embassy in London on April of 2017, protesters scattered pink triangles with messages written “Stop the death camps.” Three months later, the German parliament voted unanimously to pardon gay men convicted of homosexuality during World War II, awarding €3,000 to the 5,000 men still living, and €1,500 for each year they were imprisoned. The vote came about 15 years after the issuing of an official apology and almost a decade after the unveiling of a memorial to gay Holocaust victims in Berlin. Another well-known memorial is the Pink Triangle Park in the Castro district in San Francisco, which calls itself “the first permanent, free-standing memorial in the U.S. to gay Holocaust victims.”

The last death of someone forced to wear the pink triangle during the Nazi era is believed to have come in August of 2011, with the death of Rudolf Brazda at the age of 98. The symbols of pride that will be proudly worn around the world this month are a reminder of both what he survived and the pride that came after.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Olivia B. Waxman at olivia.waxman@time.com