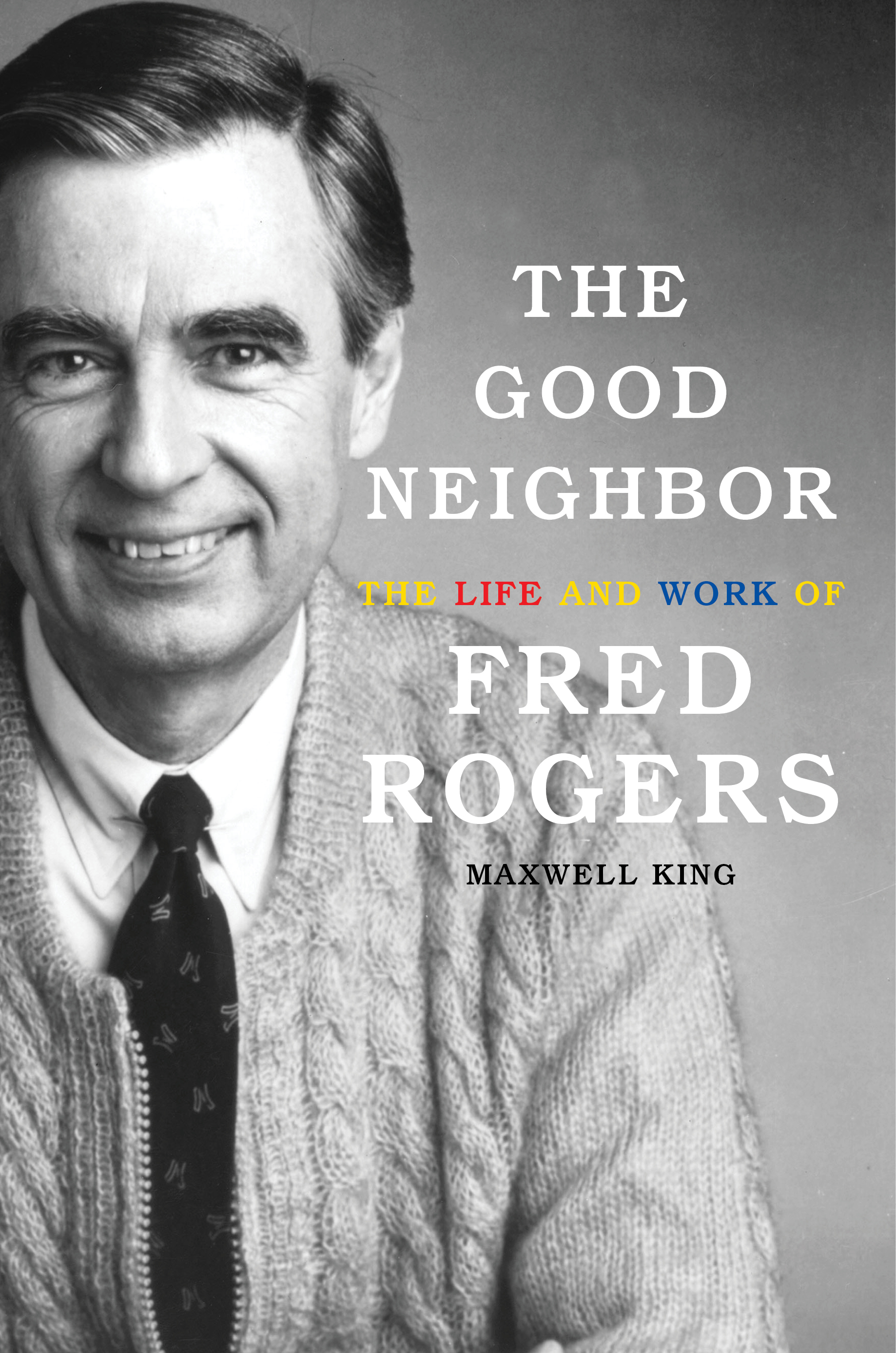

It’s been a big year for Mister Rogers: in addition to marking the 50th anniversary of the national debut of Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood, 2018 also brings a documentary about Fred Rogers (who died in 2003) and the announcement that he will be played by Tom Hanks in an upcoming feature. And, later this summer, Maxwell King’s The Good Neighbor: The Life and Work of Fred Rogers will add to that list, as the first full-length biography of the television icon.

To celebrate June 1, which is Children’s Day in many countries around the world, here’s a sneak peek at the first pages of that book:

Fred Rogers had given some very specific instructions to David Newell, who handled public relations for the PBS children’s show Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood. Rogers said he wanted no children — absolutely none — to be present when he appeared on The Oprah Winfrey Show in Chicago. No children? How could that be? By the mid-1980s, Rogers was an icon of children’s television, known for communicating with his young viewers in the most fundamental and profound way. Why would he want to exclude them from a program showcasing his views on how they should be understood and taught?

But Fred Rogers knew himself far better than even friends like Newell, who had worked with him for decades. He knew that if there were children in the studio audience, he wouldn’t focus on Winfrey’s questions, he wouldn’t pay heed to her legion of viewers, and he wouldn’t convey the great importance of his work. The children and their needs would come first. He couldn’t help it, never could help it. Decades before, Rogers had programmed himself to focus on the needs of little children, and by now he had reached a point at which he could not fail to respond to a child who asked something of him — anything at all.

He asked David Newell (who also played Mr. McFeely, a central character on Rogers’s program) to be clear with Winfrey’s staff: If there are children in the audience, Fred knows he’ll do a poor job of helping Oprah to make the interview a success. But the message wasn’t received. When Rogers came before Winfrey’s studio audience on a brisk December day in 1985, he found the audience composed almost entirely of families, mainly very young children with their mothers.

Winfrey’s staff had decided that after she interviewed Rogers, it would be fun to have him take questions from the audience, and maybe provide some guidance to mothers. And he certainly tried, telling them that to understand children, “I think the best that we can do is to think about what it was like for us.” But the plan didn’t succeed. As soon as the children started to ask him questions directly, he seemed to get lost in their world, slowing his responses to their pace, and even hunching in his chair as if to insinuate himself down to their level.

This wasn’t good television — at least, good adult television. Everything was going into a kind of slow motion as Fred Rogers became Mister Rogers, connecting powerfully with the smallest children present. He seemed to forget the camera as he focused on them one by one. Winfrey began to look a little worried. Although she was still about a year away from the national syndication that would make her a superstar, her program was already a big hit. And here she was losing control of it to a bunch of kids, and what looked like a slightly befuddled grandfather.

Then it got worse. In the audience, Winfrey leaned down with her microphone to ask a little blond girl if she had a question for Mister Rogers. Instead of answering, the child broke away from her mother, pushed past Winfrey, and ran down to the stage to hug him. As the only adult present not stunned by this, apparently, Fred Rogers knelt to accept her embrace.

Minutes later, he was kneeling again, this time to allay a small boy’s concerns about a miniature trolley installed on Winfrey’s stage to recall the famous one from his own show, the trolley that traveled to the Neighborhood of Make-Believe. The boy was worried about the tracks, which seemed to be canted precariously at the edge of the stage. As the two conferred quietly, Winfrey stood in the audience looking more than a little lost. Seeing that the show was slipping away from her, she signaled her crew to break to an ad.

For Fred Rogers, it was always this way when he was with children, in person or on his hugely influential program. Every weekday, this soft-spoken man talked directly into the camera to address his television “neighbors” in the audience as he changed from his street clothes into his iconic cardigan and sneakers. Children responded so powerfully, so completely, to Rogers that everything else in their world seemed to fall away as he sang, “It’s a beautiful day in the neighborhood.” Then his preschool-age fans knew that he was fully engaged as Mister Rogers, their adult friend who valued his viewers “just the way you are.”

It was an offer of unconditional love — and millions took it. Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood often reached 10 percent of American households, five to ten million children each day who wanted to spend time with this quiet, slightly stooped, middle-aged man with a manner so gentle as to seem a little feminine.

Over time, as new generations of parents — some of whom had grown up with the Neighborhood themselves — swelled the ranks of his admirers, Fred Rogers achieved something almost unheard of in television: He reached a huge nationwide audience with an educational program, a reach he sustained for almost four decades. Rogers became a national advocate for early education just at the time that psychologists, child-development experts, and researchers worldwide were finding that learning that takes place in the earliest years — social and emotional, as well as cognitive — is a crucial building block for successful and happy lives.

Mister Rogers’s appeal was evident from the beginning of his career, as the managers of WGBH in Boston discovered one day in April 1967. At that point, his program aired on the Eastern Educational Network (a PBS precursor) and was called Misterogers’ Neighborhood. It had been shown regionally for only a year. Recognizing its popularity, the managers organized a meet-the-host event and broadcast an invitation for Rogers’s young viewers to come to the station with their parents. The staff was prepared for a crowd of five hundred people.

Five thousand showed up. The line stretched down the street toward Soldiers Field, where the Harvard football team played, and created traffic slowdowns reminiscent of game days. The station quickly ran out of snacks for the children. As the line wound into the studio, Rogers insisted on kneeling to talk with each child, just as he would on Oprah Winfrey’s show nearly two decades later. The queue got longer and longer until it stretched past the stadium.

Excerpted with permission from The Good Neighbor: The Life and Work of Fred Rogers by Maxwell King, which will be released by Abrams Books on Sept. 4, 2018.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Biden Dropped Out

- Ukraine’s Plan to Survive Trump

- The Rise of a New Kind of Parenting Guru

- The Chaos and Commotion of the RNC in Photos

- Why We All Have a Stake in Twisters’ Success

- 8 Eating Habits That Actually Improve Your Sleep

- Welcome to the Noah Lyles Olympics

- Get Our Paris Olympics Newsletter in Your Inbox

Contact us at letters@time.com