It was a chilly Friday afternoon in early February, and a group of young activists huddled around a table inside a modern, earthy café in Atlanta’s West End neighborhood, planning their next moves. Already, the group had worked to combat school privatization in the city. They had also plotted “school-to-activism pipelines” for local kids. The cause at hand now was a new stadium, and how to mitigate its financial impact on the longtime residents of a black community in its shadow.

None of it could be called schoolwork, yet it was exactly what Eva Dickerson aspired to three years ago when she chose to attend nearby Spelman College. The four-year women’s school is one of the country’s highest-ranked historically black colleges and universities (HBCUs), a community of 101 schools that, as a group, have re-emerged as centers of youth activism in the U.S. As with Dickerson herself, the transition has come in stages.

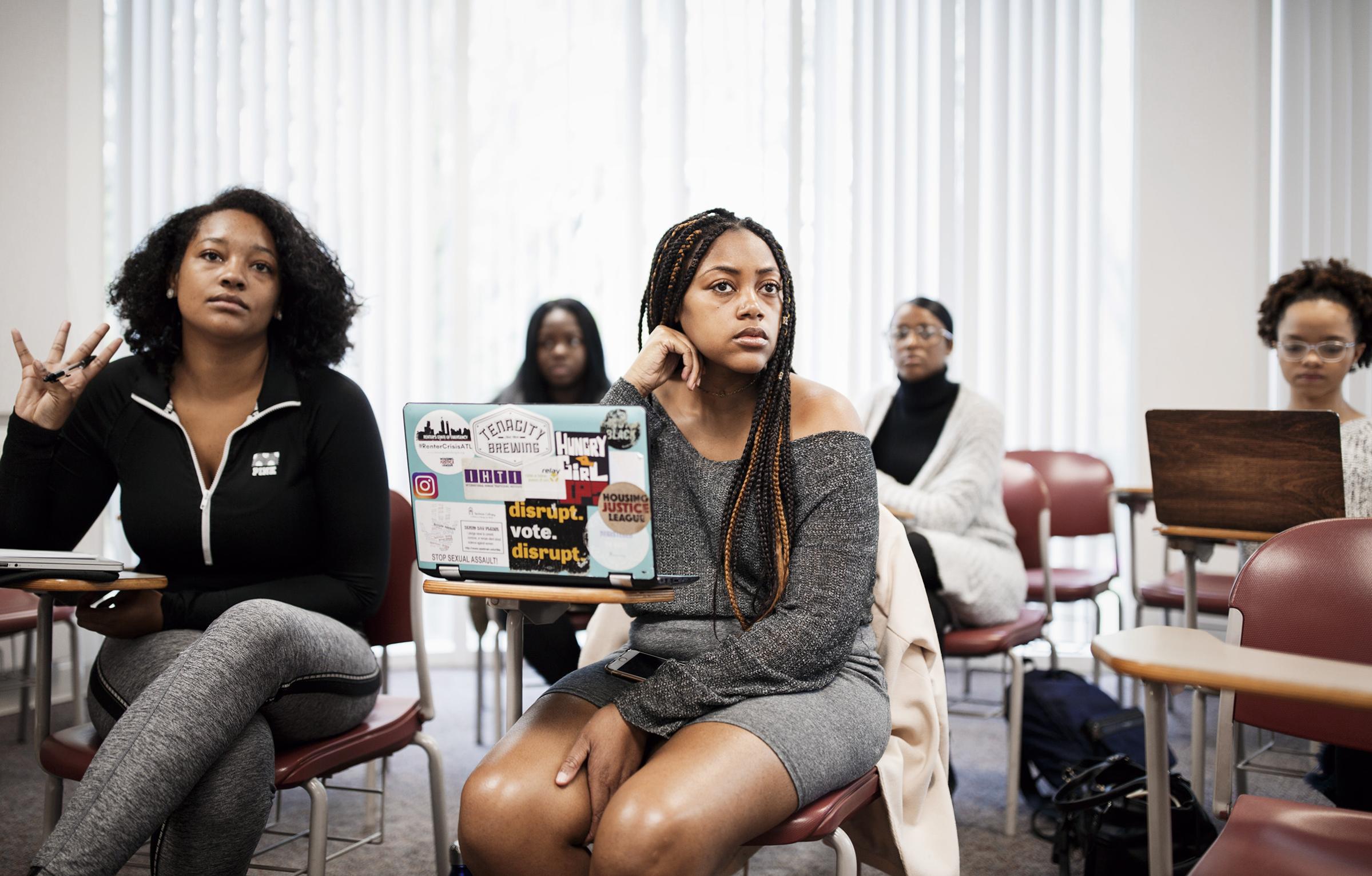

The college junior was 16 years old when Trayvon Martin was killed in 2012. Her senior year in high school, she attended her first protests, in Baltimore, in the wake of Freddie Gray’s death. “I was just like, Yo, I’m black, I’ve got to do something,” Dickerson says. “And then I got to Spelman, and there were black people doing things consistently and making changes.” She wanted to be a part of the movement.

The campuses that served as incubators for the civil rights movement in the mid–20th century are experiencing something of a renaissance. Freshman enrollment is up at 40% of HBCU schools, says Marybeth Gasman, director of the Penn Center for Minority Serving Institutions. Cascading national episodes of racial tension account for much of the surge, but the new energy also draws on tension–never new–between students and administrators. As in past generations, students fired by a desire for change are less inclined to hew to the line of often institutionally minded leaders, and protests have rocked institutions from Atlanta to Washington, D.C., where students at Howard University occupied the administration building for nine days this spring.

But in this community, the election of Donald Trump also factors–and not only as a target of student protests. The President, who exit polls showed carried only 8% of the African-American vote in 2016, famously hosted a Oval Office photo op with the leaders of HBCUs, which rely on federal funding for a significant portion of their budgets. And with both houses of Congress being controlled by Republicans, administrators and supporters have been obliged to balance the energy of resurgent student activism with the continuing practical needs of an educational institution. “It is a dual-edged sword,” says Crystal deGregory, director of Kentucky State University’s Atwood Institute for Race, Education and the Democratic Ideal.

Started after the Civil War in the basements of churches, old schoolhouses and cabins, HBCUs were the first institutions dedicated to the education of former slaves and free black people. From their modest beginnings, they have produced alumni who transformed America, from W.E.B. Du Bois to Thurgood Marshall.

In the early 1960s, HBCU students played a pivotal role in the civil rights movement. The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, which fought segregation, was formed after a conference of 300 students at North Carolina’s Shaw University. Four students at North Carolina A&T State University in Greensboro launched the sit-in movement at a nearby lunch counter. Congressman John Lewis, then a student at Fisk University in Tennessee, was one of the original 1961 Freedom Riders, who galvanized civil rights protests across the nation.

But as major universities desegregated, competition for students grew, leading to declining enrollment at HBCUs. This posed a challenge for the schools, which rely disproportionately on tuition for their operations. Small endowments, drops in philanthropy and low investment also exacerbated financial woes. Because HBCUs are reliant on federal funding, small changes in Washington can hurt on campus. In 2011, the Obama Administration altered the credit underwriting requirements for Parent PLUS college loans, making it harder for many families to qualify. Black institutions were hit particularly hard–overall, HBCUs lost an estimated $150 million by 2013, before the policy was reversed.

Those challenges have not stopped students from seeking out black college experiences. In the wake of highly publicized antidiscrimination protests at the University of Missouri in 2015, applications spiked at many HBCUs, according to Dillard University president Walter Kimbrough. North Carolina A&T State University enrolled its largest freshman class ever in 2017, boosting total enrollment to a record 11,877 students. At Spelman, applications jumped from 5,000 in 2015 to 8,600 last year, and another 16% for 2018. But the resurgence has not been universal. Many schools still struggle financially. Three HBCUs have closed over the past three years.

If some of that enrollment bump came from the rise of Donald Trump, he also helped fuel the renewed activism on campus. Spelman Student Government Association president Jill Cartwright recalls that the mood at a 2016 election-night watch party at Martin Luther King Jr. International Chapel on the Morehouse campus shifted from celebration to gloom as the results came in. When Trump won Ohio, Cartwright recalls, the room fell silent. “I’ve been to church services in King Chapel, [and] it has never been that quiet,” she says.

The shock of the election at first produced mourning at the Atlanta University Center (AUC), which comprises Spelman, Morehouse and two other institutions. Professors, administrators and student groups held open sessions where the community could express their emotions. But activists and administrators soon turned to organizing. “We know that we don’t have a whole lot of power when it comes to the President,” says Cartwright. “But we do have power at our institutions, and that’s where it begins.”

The result has been activism on a number of fronts. In 2017, as the #MeToo movement roiled the nation, a group of students broadcast the names of alleged rapists and rape apologists on the campuses of Morehouse and Spelman. This controversial action led to the creation of a task force to establish anti-assault and healthy-relationship training in the curriculum. After the then Atlanta mayor closed one of the city’s most utilized homeless shelters last spring, 300 AUC students slept outside for 24 hours and raised more than $11,000 to address the issue. Last fall, Mary-Pat Hector, a junior at Spelman, ran for city council in a newly incorporated city in Georgia, losing by just 22 votes.

Dickerson, the Maryland native, says HBCUs spur the renewed level of student engagement. “HBCUs hold a critical role in the resistance,” she says, “And not just to Trump’s presidency, because that’s an incomplete resistance.” The question for HBCU leaders has been how to manage and respond to that resistance when it targets administrators themselves.

Spelman is a small institution; the student body is made up of about 2,100 students. The community is so close-knit, students call their peers “sisters.” Mary Schmidt Campbell, the school’s 10th president, lives in a house in the middle of campus, which means she interacts with students every day. Increasingly, those conversations include challenges and questions. “If you can’t speak up here, where can you speak up?” she says.

Spelman student-activist Hector says: “HBCUs are a safe space, but they’re not a brave space. We’re being taught to speak everywhere but here.” Last winter, Hector led two dozen of her peers on a six-day hunger strike that ended after Morehouse and Spelman agreed to offer free meals to students who live off campus.

Elsewhere, students at Tennessee State University have staged demonstrations over the condition of the school’s dorms and their limited capacity. At Hampton University, students have been in an uproar about campus safety, facilities and dining options. No campus has seen more disruption than Howard, where a stunning building occupation forced the university to meet 11 of the students’ 12 demands, including changes to its sexual-assault policy and the establishment of a student-led food bank.

The campus cross-pressures have a particular quality under Trump. A month after his Inauguration, he hosted more than 80 HBCU presidents at the White House. But during their stay in Washington, Education Secretary Betsy DeVos clumsily called black schools pioneers of “school choice,” which offended college leaders, given the schools’ history with segregation and Jim Crow. HBCU activists dismissed the meeting as little more than a photo op; they greeted with mockery online the images of Trump adviser Kellyanne Conway kneeling on an Oval Office couch to snap a group photo.

A month later, Trump released a budget proposal that included massive cuts to Pell Grants, on which many black college students rely, and the White House suggested that a federal program for HBCUs might be unconstitutional, because it allocates funds on the basis of race–an idea it walked back amid public outrage. At Howard and Bethune-Cookman universities, high-profile guests with ties to the Trump Administration were met with protests.

All the while, college administrators have remained engaged with lawmakers in Washington, and as a result they have seen some gains. The Department of Education restored year-round Pell Grants in the summer of 2017. The omnibus spending bill passed in March included a 14% boost in federal funding for HBCUs, additional money for Pell Grants and a $10 million increase to the HBCU Capital Financing Program, the same program Trump appeared to criticize last May.

DeGregory of Kentucky State University says the campus activism, whether it targets big national issues or local administrative ones, shows that HBCUs are carrying forward their key missions of education and activism in a new era. Race relations are volatile, and the Trump Administration has played a role in stoking the flames, she says, but HBCUs have survived much throughout their 150-year history. And right now, she says, “we’re doing what we’ve always done.”

At Spelman, Campbell says she tries to balance renewed student activism with the institution’s long-term goals, convinced that the 137-year-old college is at its best when it tends to both: it was partly because of student pressure, from Cartwright and others, that last fall Spelman became the first single-sex HBCU to allow transgender students to enroll.

“Activism is an extremely important part of what your life here at Spelman should be,” Campbell says. “I think of protest as a way of shining a light on things that perhaps need to be enlightened that we wouldn’t know about.” On that, Dickerson and other activists at the West End café find no reason to dissent. Says Dickerson: “I feel like my ancestors placed me here–placed all of us here–for a reason.”

Correction: The original version of this story incorrectly described a food pantry linked to Howard University. Students plan to run the pantry in a neighborhood near the school, not on Howard’s campus.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com