In 2015, 33,091 people died from opioid overdoses in the U.S. My sister was one of them. She passed away on July 31, 2015 at the age of 44. I often think about her last day and what her final moments were like. I also think about the person who gave her the drugs that ended her life. Below is what I might say to that person if we ever met.

DEAR DEALER,

Hey, man, what’s up? I’m saying “man” because most of the people who blew up my sister’s phone offering and seeking drugs were men. Men who had negative impacts on my sister’s life. Since I don’t know your name, I’ll just call you Dealer. You had the greatest and most negative impact on my sister’s life: You killed her.

In high school, at the height of the Just Say No movement in the late ‘80s, we were taught that kids who used drugs were pariahs, weak. They just couldn’t say no. But the people who sold the drugs, they had power. Drug dealers were dangerous, but also a little sexy. “I bet he’s like, a drug dealer.” But to call you a drug dealer here, with that same reverence, is naive, out of touch. I’m an adult now. I know better. I know addicts, and people in recovery; I’ve been around lots of drugs and have done my fair share. So, I’m familiar with your world, familiar enough to know that most people who call on you for their drugs probably refer to you as their dealer. Similar to how they refer to other helpful people in their lives: my mechanic, my hairdresser, my chiropractor, my dentist, my deli guy…my dealer.

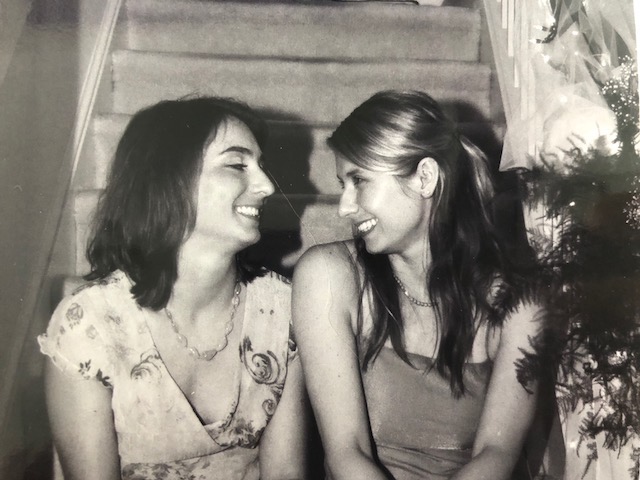

What did you call my sister? My sister, Sasha, who I think you knew. I hope you didn’t call her Sash because that’s what a lot of people who loved her called her, and I find it hard to believe that you loved her. Did you call her by her name? Or, “lady?” How about, “hot mess,” when she was out of earshot? Or maybe you created a nickname for her like “purple,” the color of her car. The same car she was found in, slumped over, in the parking lot of a seafood restaurant off the side of the highway, according to the police report.

When she died, I was seven months pregnant, and when I gave birth the doctors gave me the same drug that killed her to ease my 46-hour labor. My husband had to pull my physician aside, and beg him not to tell me that he was about to inject me with the same drug that took my sister’s life. The drug you gave to her. The drug you mixed with heroin. The drug that’s 50 to 100 times more powerful than morphine. The one that stopped her breath, then her heart. Fentanyl.

I THINK ABOUT YOU ALL THE TIME. Almost every day. You’re the only one who knows some very important things about how my sister died, so I feel like I deserve to know you. I deserve at least five minutes of your time. You may be the last person who saw her alive, and I’m a little jealous. Are you still alive? I feel like you are. And I’m angry about that. But if I found out that you’re dead, I might be angry about that too. Sometimes, I think about hurting you.

It’s important to me that you understand who you destroyed. Sasha was valedictorian of her high school class. She studied psychology at Yale, and then went on to earn two master’s degrees in social work and public health. She once had a pet rat that she walked on a ferret leash. She once stapled herself into a homemade pleather Bat Girl costume for Halloween. At one point, she knew the names of most of the homeless people in New Haven. She organized trips for her clients to see me perform in Shakespeare plays in a park in New Haven. She gave me my taste in music, from Joni Mitchell to Funkadelic. Sasha was an incredible horseback rider. Her legs were iron cables. She loved to put me in “the vice,” a move inspired by our love of WWF wrestlers. She’d wrap her brawny thighs around me, and squeeze until I almost couldn’t breathe. Toward the end of her life, when she couldn’t commit to much anymore, she still loyally volunteered for an organization that prepares and delivers meals to homebound patients with AIDS. Her voice was singular, you knew she was coming before you ever saw her. Her memorial was full of people who said she made their lives fuller. The director of the gospel choir she sang with up until her death created a new verb in her honor: to Sashify, which means to infuse with exuberance.

Who are you? Did you know Sasha well enough to call her a friend? Are you one of the people she talked to and texted with on her last day? Are you the ex-boyfriend who kept harassing her? The one who introduced her to oxycontin? That guy? Are you one of those friends who didn’t have the decency to show up to her memorial? Were you feeling guilty about something?

Tell me who you are. Were you with her when she died? Both her windows were rolled down when she was found. Were you in her passenger seat? Did you get scared and run? Did you sit there and watch her die? Tell me. What were her last moments like? What were her last words? Do you think she knew that she was going to die that day? Do you think she was scared? I hope she wasn’t scared.

TO BE FAIR, MY SISTER DEALT DRUGS TOO. My husband gently offered me this reminder as I was writing to you. I quickly defended her: “Yeah, but she never killed anyone.” He replied, gently, “You don’t know that.” I was stunned, but it’s true, I don’t know that. And the fact is, she could have killed someone. My worst fear when she was alive was that she would be driving around high, and kill someone. That thought kept me up at night. And no, I don’t know if something she sold resulted in someone’s death. I don’t know if someone else’s sister is writing this same letter to her.

But there’s a system of bartering and shuffling in the drug world that often makes it hard to tell who’s the dealer and who’s the customer. My sister sold drugs for other dealers, as evidenced by the notes in the back of her daybook with peoples’ initials, and how much they owed or paid her, and how much she owed and paid in return. Many times her payment was free drugs. When she was found dead in her car, she had only five cents in her wallet. This was not high rolling dealing. This was survival.

Is dealing just a way for you to survive too? If so, where does that leave us? What would happen if we ever met? Will I unleash all of my rage on you? Or, will I look into your eyes and weep because you’ll look just like my sister. You’ll be someone, like my sister was, who can’t be around their family anymore because pretending is so hard, because you’re sick, and getting high is the only way to maintain some equilibrium. I know anger isn’t sustainable, but I’m afraid to feel the sadness — it’s protecting. My anger is control, it gives me say. My sadness knows I have neither.

Until we figure out where we go next, I’ll leave you with this: I’ve done the math, and as of March 11, 2018, at 6:49 p.m., I’ve lived longer than my big sister who was born two-and-a-half years before me. This makes no sense. You’ve knocked the universe off course. So F-ck you. F-ck you, because you may still be here and there will never be another her. I will always think about you. You’re my dealer now. You’ve dealt me a life without Sasha. I’m here to remind you of that. And I’m not going anywhere.

Yours Forever,

The Sister

To hear an audio version of this story, listen to it on the This American Life website or on any podcast app.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com