For much of the 20th century, the United States government locked women in concentration camps. “Concentration camp” — that isn’t my phrase; it was written by a woman named Billie Smith, in a lawsuit she filed against the government.

Smith’s travails began on the evening of June 13, 1942. A thunderstorm and fierce winds had swept through Little Rock, Ark., just hours before. That night, 33-year-old Billie Smith was arrested in her hotel room for violating two sections of a Little Rock ordinance that prohibited prostitution and “immorality.” Smith quickly pleaded guilty; to get out of jail, all she had to do was pay a fine of $10. Yet after she paid the fine, Little Rock’s health officer informed Smith that he was going to force her to undergo a medical examination. He suspected she had a sexually transmitted infection. The health officer took vials of Smith’s blood for a syphilis test, and closely examined her vagina for signs of gonorrhea. While the health officer awaited the results of the blood test, Smith waited behind bars, in the Pulaski County jail.

After a day, the test results were back: Smith had syphilis; what’s more, the health officer said she had gonorrhea, too. He ordered that she be quarantined in a detention hospital in Hot Springs, Ark.

Smith, who had already paid her fine, thought this was ludicrously unfair. So on June 16, she filed suit, demanding that the Pulaski County sheriff release her at once. She insisted that the ordinance that enabled her imprisonment was unconstitutional. In a highly significant turn of phrase, she further asserted that, simply because she had an infection, she was about to be locked away in a “concentration camp.”

Billie Smith was not alone. Indeed, for much of the 20th century, tens, probably hundreds, of thousands of American women were detained and subjected to invasive examinations, usually conducted by male physicians, for sexually transmitted infections (STIs). These women were imprisoned in jails, “detention houses” or “reformatories” — often without due process — and there treated with painful and ineffective remedies, such as injections of mercury. They were locked in buildings that often had barbed wire, armed guards or both. Some of these imprisoned women were beaten or otherwise abused; some were sterilized.

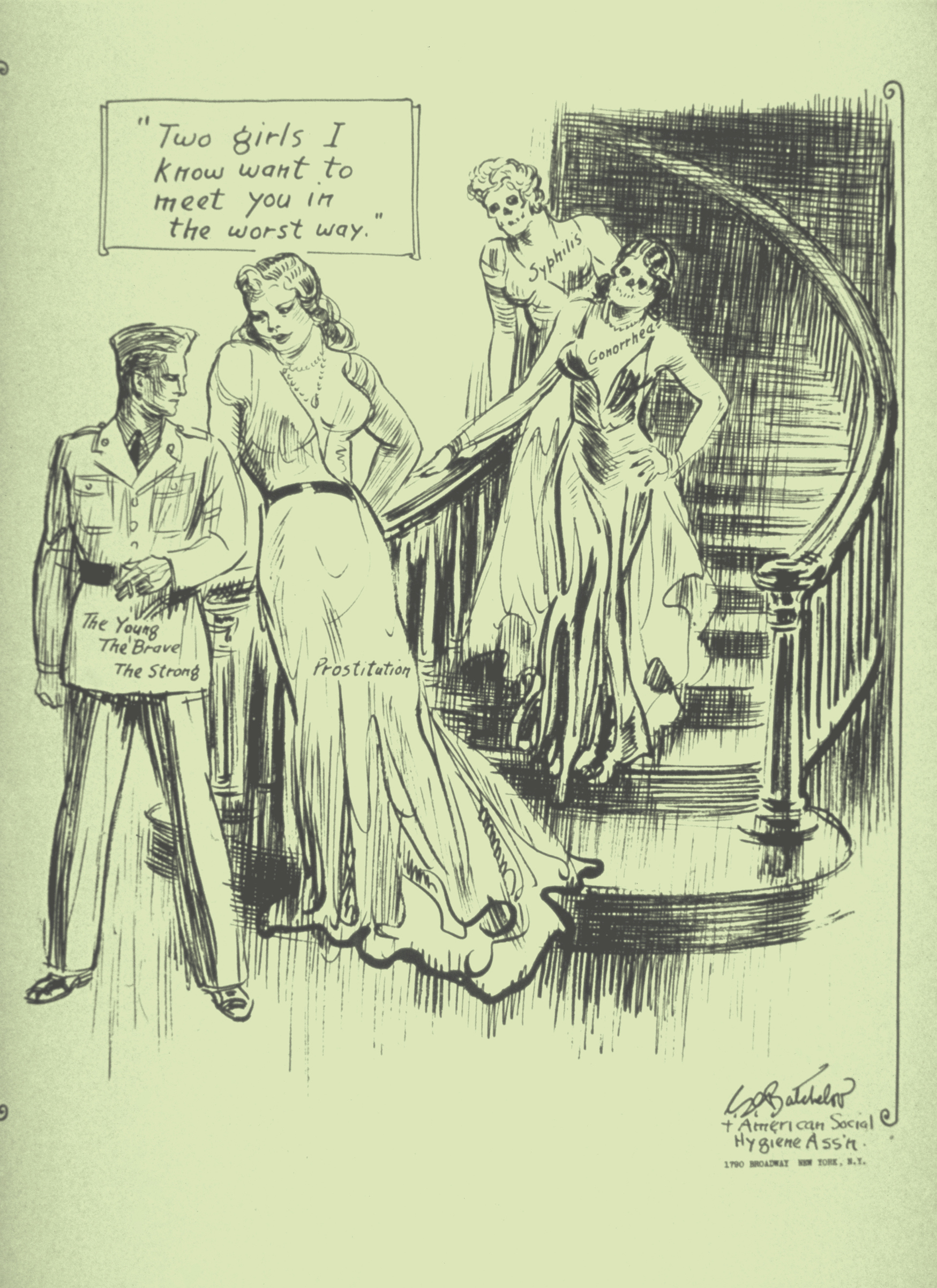

These women were incarcerated as part of a government campaign known as the “American Plan.” Initially conceived during World War I as a federal project to protect soldiers from STIs and prostitutes — who were believed to nearly always carry STIs — it later expanded to reach into American communities at large, with state and municipal governments encouraged to pass their own parallel laws. Eventually, the Plan became one of the largest and longest-lasting mass quarantines in American history.

Under the American Plan, government officials were empowered to scour the streets looking for any woman whom they “reasonably suspected” of carrying an STI. These officials detained countless “suspected” women, examined them without their consent, and locked up those who tested positive — as well as a number who didn’t, but who were deemed sufficiently “immoral” or “promiscuous.” The Plan operated more or less continuously in many places during the 1910s, 1920s, 1930s and 1940s. During World War II, it was reinvigorated on a national level, though local officials had never truly ceased to round up and lock up women for having STIs or being suspected of prostitution. In some places, officials continued to enforce the Plan as late as the 1970s, and laws originally passed under the Plan were referred to in the 1980s and 1990s to justify the proposed quarantine of another group of individuals with a stigmatized infection: HIV/AIDS. Each of these laws remains on the books, in some form, to this day.

As for Billie Smith, she remained behind bars for four days. Then, on the afternoon of Saturday, June 20, she had her day in court. Following a hearing, Judge Guy Fulk ruled that Little Rock’s ordinance was void, describing it as “dictatorial.” But when the Arkansas Supreme Court heard the city’s appeal, it overruled Judge Fulk, declaring that Smith’s status as infected “affects the public health so intimately and so insidiously, that consideration of delicacy and privacy may not be permitted to thwart measures necessary to avert the public peril.” The court overturned Judge Fulk’s invalidation of the ordinance and ordered the Pulaski County sheriff to immediately remand Smith to “isolation and quarantine.”

Yet when the Little Rock authorities went looking for Smith, she was nowhere to be found. Smith had vanished.

Rather than face the chance of reincarceration and forced STI treatment, Billie Smith had fled. It was another month before Smith was captured in a Memphis hotel and fined $127 for several crimes, including prostitution. Smith was sent to what the Arkansas Gazette called an “isolation unit” for STI treatment. It wasn’t until the end of 1942 that she was returned to the Pulaski County jail, and then finally to the detention facility in Hot Springs — the institution she had called a “concentration camp” months before.

That still wasn’t the end of Billie Smith’s saga. After just a few days in the Hot Springs facility, Smith and another woman attempted to escape, and, after this, the Hot Springs authorities refused to take them back. Smith remained behind bars for a few more weeks, but she successfully avoided spending her sentence in Hot Springs.

Hundreds of women locked up under the American Plan did just what Smith did: attempted to escape from the detention facilities in which they were held. At least one woman jumped out a window to her death; another woman leapt from a moving train to try to avoid incarceration. Others would riot and destroy their sites of incarceration; many would burn these buildings to the ground. Still others would go on hunger strikes or use the press to call attention to the conditions under which they suffered.

The case of Billie Smith illustrates the ongoing resistance of women incarcerated under the American Plan. She attempted to defy the Arkansas authorities in almost every conceivable way: by suing them, by fleeing the state, and then by trying to break out of her detention hospital.

What The Handmaid’s Tale Gets Right—and Wrong—About the History of Women and Resistance

To me, the case of Billie Smith also exemplifies something more: the importance of using individuals’ own words when attempting to tell their stories.

Billie Smith used the phrase “concentration camp.” Later, as I was piecing together her story, several people counseled me not to use that phrase — it was too politically charged, too associated with the Holocaust and other genocides. It would distract from the story I was trying to tell.

Yet this was the phrase Smith had chosen. And it was not one she’d chosen at random. At the time, the phrase appeared regularly in American newspapers to refer to what was happening in Europe, and was also widely used to refer to the internment of Japanese-Americans on the West Coast. Smith’s invocation of the phrase “concentration camp” — literally the only record we have of her own voice — reveals a notable degree of worldliness. It also suggests that women being held against their will under the auspices of the Plan connected themselves to a larger pattern of resistance against governmental violence and disdain.

Furthermore, Smith was not alone. A month after the Arkansas Supreme Court issued its ruling in her case, and weeks before she was tracked down in Memphis, the Associated Press ran a story about “concentration camps for diseased prostitutes presumably after they have been apprehended through infecting soldiers.” One wonders if the fleeing Smith glimpsed this article in a newsstand somewhere.

Smith’s story tells us something about how we remember the past, and whose words we read or hear when trying to learn more about it. When those of us who have not lived through the traumas of the past do not ground our stories in the voices and words of those who did, we risk infecting those stories with our own contemporary, privileged biases and assumptions. It is inevitable that a writer shapes the story she tells, but that shaping is a matter of degree, and making extensive use of the voices of historical actors means that a writer’s story is more reflective of her subject’s story.

When historians or journalists write about people, they must strive to use their writing to give voice to those people. A historian writing about slavery must use the surviving words of enslaved people; a journalist covering refugees must allow herself to become a mechanism through which refugees can have their truths heard.

For anyone writing Billie Smith’s story not to use her pair of surviving words would allow her captors — who tried to marginalize and “fix” her — to win. It would be a victory for those throughout history who have tried to silence others. It would not just be incomplete. It would not just be inaccurate. It would be erasure.

Scott W. Stern is the author of The Trials of Nina McCall: Sex, Surveillance, and the Decades-Long Government Plan to Imprison ‘Promiscuous’ Women, from which this essay is adapted.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com