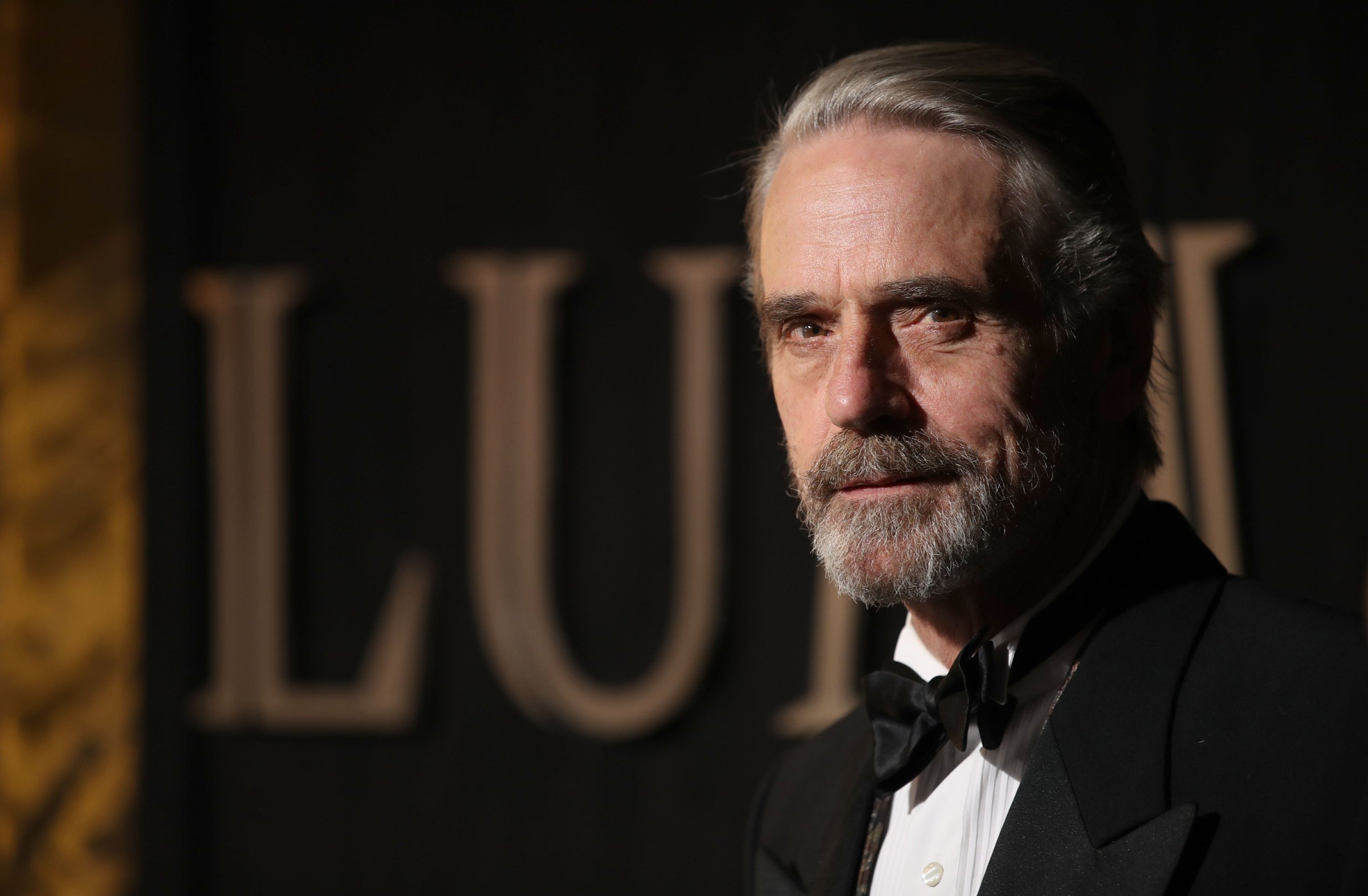

Taking into account tone, speed and intonation, a 2008 British study found that the actor Jeremy Irons has close to the ideal voice. Apparently, he speaks at an optimally pleasing 200 words per minute and pauses for 1.2 seconds between sentences. Irons, who lives in an Irish castle in the rare periods when he’s not working, is now performing at BAM in New York City in a dauntingly long and critically acclaimed production of Eugene O’Neill’s Long Day’s Journey Into Night, transferred from London’s West End. The actor, who does extensive voice work in addition to his film and stage appearances, also recently released an audio book, The Poems of T.S. Elliot.

While he doesn’t require green M&M’s in his dressing room when he travels, he does like to have a place with a backyard (for smoking and for his dog), room for his “big Martin” guitar and access to a motorcycle for tooling around between performances. Having found such a spot in Brooklyn, he talked to TIME about giving voice to evil, forgetting lines and the hardest part he’s ever played.

TIME: Your previous audiobook of Nabokov’s Lolita is considered by many to be the gold standard for audiobooks. Any recollections from the recording session?

Jeremy Irons: After I had been approached to record it, I discovered the company intended an abridged version. I felt, had Nabokov wanted it abridged he would have written it shorter, and I suggested to his son Dmitri that he might insist we record it as written. When I arrived at the studio in North London, my producer told me we would need an extra day to record it in its entirety. I explained I only had two days before I was to fly to work in the U.S. I told her I would read it very quickly, and asked her not to interrupt me unless absolutely necessary. The read, as a result, has a briskness and flow that without those time constraints might not have surfaced.

You also give voice to one of the most evil mammals in the history of animation, Scar, in The Lion King. How do you portray evil with voice alone?

The word unctuousness comes to mind, but I wonder if it isn’t the contrast between what a character says and how he says it, and what he actually does that projects his evil nature. “One may smile, and smile, and be a villain,” as Hamlet said.

You have played some nasty people. Who was your favorite villain to portray?

Simon, in Die Hard with a Vengeance, is a man with whom I would enjoy spending the evening.

What is your first recollection of someone bending to your will, strictly based on your verbal power?

My first dog, indeed all my dogs, have been delightfully susceptible to it. Sadly, I do not find such success amongst humans. I remember Glenn Close telling me that when her friend Robert Duvall heard she was doing The Real Thing with me, he asked, “How can you trust a f-cker who talks like that?”

You’ve performed Shakespeare, Tom Stoppard and Eugene O ‘Neill. In terms of degree of difficulty, number of lines, emotional toll — how does O’Neill rank?

Laurence Olivier, who played nearly everything, said that James Tyrone [the role Irons plays in Long Day’s Journey into Night] was the hardest part he had ever attempted. I would agree—the hardest, and yet the most rewarding. O’Neill did not write this play to be performed, so performing it uncut, as written, requires the actors to discover from what is on the page much that is not on the page. It is not possible to play without being emotionally present at each moment.

Do you ever space out on stage? And if so, how do you recover?

To ‘dry,’ as we call it, is every actor’s nightmare. I managed to do it on our press night [for the British production of Long Day’s Journey]. At a moment in the Act 4 scene with my son, my mind went blank. Eventually, I scoured from my brain a line which got me back on track as I felt the growing realization that I had cut four pages, which included my son’s major arias. Fortunately, with an actor’s tenacity he cut back to where we should have been, leaving me with the unenviable task of repeating word-for-word a page I had already said. I tried to inflect my lines completely differently to convince the audience this was an example of the circular nature of O’Neill’s writing rather than my blunder. I’m not sure I succeeded.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com