When an unidentified drone came crashing down onto the White House grounds in early 2015, it led to doubts about what’s supposed to be the country’s most secure airspace.

The incident turned out to have been mostly harmless. The pilot, a scientist at the National Geospatial Intelligence Agency, was not charged with a crime. In fact, he called the Secret Service himself to report the crash. But his airborne misadventure raised an important question: If a well-meaning hobbyist could accidentally bombard White House property, what’s to stop someone with sinister intentions from doing something worse?

It’s an important question, considering drones have been modified to carry all manner of potentially harmful payloads, from grenade-sized bombs to drugs and other contraband. “The optic that’s important is to understand what the purpose of the drone is, and why it’s being flown in the first place,” says former Navy Vice Admiral Robert B. Murrett, who is now the deputy director of the Institute for National Security and Counterterrorism at Syracuse University. “But you have to assume the worst in terms of enforcing our aviation security.”

TIME Special Report: The Drone Era

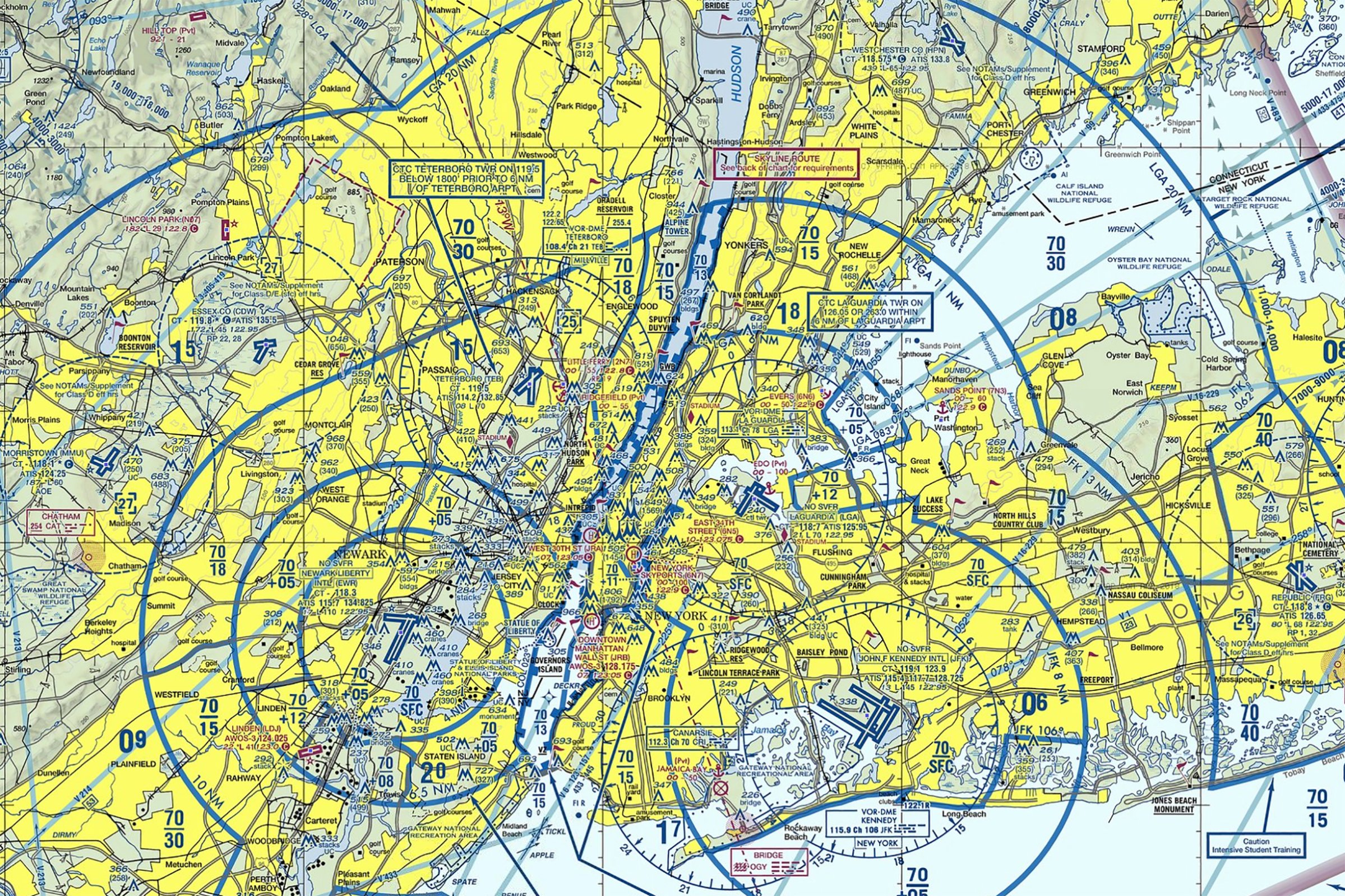

Drone pilots are supposed to follow rules laid out by the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA), which require staying away from major airports, sports stadiums and Washington, D.C., among other sensitive locations. But enforcing those rules is often difficult or outright impossible. Drones are typically too small to be effectively tracked with standard radar systems. Thanks to their onboard cameras that transmit a visual feed to a pilot’s smartphone or tablet, drones can be flown miles from their starting point, making it hard to find a pilot even if their drone is caught in a restricted area. And the FAA itself has “limited boots on the ground,” as a spokesperson put it, often leaving it up to local law enforcement groups to deal with out-of-bounds flyers. (The U.S. Transportation Department recently proposed a new rule that would allow for remote identification and tracking of drones.)

In many cases, it’s difficult to tell whether errant drone pilots are simply uninformed, reckless but mostly harmless, or legitimate security threats. But with the stakes as high as they are, giving anyone the benefit of the doubt can feel risky. As a result, a number of companies are working to enforce so-called “no-drone zones,” or areas where drones are prohibited.

One such firm is DJI, which makes some of the world’s most popular consumer drones, including the Phantom and Mavic lineups. In October of 2017, DJI introduced AeroScope, a system that helps authorities see an errant drone’s location and registration number. AeroScope is being pitched as a solution for airports, prisons and other facilities interested in keeping drones at bay. All of DJI’s drones are also equipped with no-fly zone technology meant to prevent them from entering restricted airspace.

“For us, it’s incumbent to protect the market and allow people to operate freely,” says Michael Perry, Managing Director of North America at DJI. “In order to do that, we need to enable tools that help people understand the airspace, where they should and should not be flying, and also help ensure compliance with that regulatory framework.”

Other firms are working on more extreme anti-drone measures. AMTEC Less-Lethal Systems makes shotgun shells containing Kevlar threads that, when fired, shoot a net designed to ensnare a drone, sending it crashing back to earth. A round of the shells costs less than $20; AMTEC has contracts with the U.S. Air Force and the Federal Bureau of Prisons, Director of Sales and Marketing Monica Sipp tells TIME.

Higher-end drone defense systems are also available. SearchSystem’s SparrowHawk is an approximately $11,000 modified DJI drone meant to fly near and shoot a net at other drones, rendering them immobile. There’s also the Battelle DroneDefender Counter-UAS Device, which blasts a directed stream of radio waves designed to overwhelm a drone’s GPS and remote control functions, sending targets into failsafe mode. The DroneDefender is currently available only to federal government agencies. Alex Morrow, technical director of counter-UAS programs at Battelle, declined to name its price, but he says between 200 and 300 are in circulation.

These products, in conjunction with educational outreach and regulatory efforts from national and local law enforcement agencies, may help keep drones out of protected airspace. For Scott McLean, a deputy chief in communications at the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection (CAL FIRE), new tools to keep the skies clear cannot come soon enough. Drones are banned from flying over wildfires because they can disrupt airborne firefighting operations. But McLean says CAL FIRE regularly deals with unwelcome bogeys as drone hobbyists seek fiery footage to post on social media. The rules are well publicized, McLean says, but CAL FIRE still encounters around a half-dozen unauthorized drones every year — and he’s not buying the excuse that amateur pilots just don’t know any better. “They know [the rules]. They should know. And it’s their responsibility,” McLean says. “They need to be responsible, loud and true. We have a job to do, and we’re doing it.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- L.A. Fires Show Reality of 1.5°C of Warming

- Home Losses From L.A. Fires Hasten ‘An Uninsurable Future’

- The Women Refusing to Participate in Trump’s Economy

- Bad Bunny On Heartbreak and New Album

- How to Dress Warmly for Cold Weather

- We’re Lucky to Have Been Alive in the Age of David Lynch

- The Motivational Trick That Makes You Exercise Harder

- Column: No One Won The War in Gaza

Write to Jamie Ducharme at jamie.ducharme@time.com