In a muddy clearing about half the size of a football field, several thousand rice paddy planters and taxi drivers join an elbow-to-elbow scrum, waiting in darkness in Jerlun, a rural village in northwest Malaysia. They snack on fried corn and peanuts, slap away mosquitoes, and use their cellphones to navigate over boggy rivulets. And then, well-after 10 p.m., he arrives. The crowd ululates and the black BMW disappears as supporters cut toward it. When the 92-year-old patriarch of modern Malaysia stiffly alights, he is greeted the chant: long live Mahathir. The nation’s longest-serving prime minister has returned.

After leading Malaysia from 1981 until 2003, Mahathir Mohamad has now stepped out of retirement in a bid to unseat his wayward former protégé, current Prime Minister Najib Razak in elections on May 9. As the unlikely leader of the opposition he once oppressed, Mahathir is galvanizing the fight to end his own former party’s 61-year monopoly on power.

Feared, loathed and venerated, Mahathir was many things during his 22 years as prime minister, but never an apologist. Yet he tells voters in this constituency near the Thai border and not far from his own birthplace that while he does not have much time left, he’s come back to correct his biggest mistake: appointing scandal-tainted Najib his successor.

Mahathir, who has been a titan of Malaysian politics for longer than Najib has been alive, helped install the prodigal son of the nation’s second prime minister, shunting aside a previous inheritor, “sleepy” Prime Minister Abdullah Badawi, in the process.

“I have to apologize because it was I who worked so hard to have Najib replace Badawi,” he tells his rapt audience at the Jerlun rally. “I thought Najib would follow in the footsteps of his father … but unfortunately, Najib has a different philosophy. Najib believes cash is king.”

Najib is accused of pilfering over $1 billion from the graft-tainted state investment fund, 1Malaysia Development Berhad (1MDB). While he has denied any wrongdoing, at least 10 countries are investigating the money-laundering case, including the U.S. Justice department. Then U.S. Attorney General Jeff Sessions called it “kleptocracy at its worst.” By Mahathir’s count, this scandal derailed the oil-rich nation’s rightful transition into fully developed nationhood.

A doctor by training, Mahathir spent his career diagnosing Malaysia’s ills and prescribing economic fixes. He bootstrapped the nation from an agrarian post-colonial state to a buzzing manufacturing powerhouse exporting semiconductors and commodities. Considered a disciplined economic pioneer, Mahathir buoyed the fortunes of the ethnic Malay majority, oversaw economic expansion of 8% per year and doubled the per capita income to $3,900. The gleaming Petronas Towers, then the world’s tallest building, were erected as symbol of the nation’s ascendance.

But Mahathir also helped entrench the centralized government that Najib exploited. Under Mahathir, critics were jailed without trial, newspapers shuttered and judges sacked.

“Mahathir turned the state into a machine for personalized rule,” says Chin-Huat Wong, a political scientist with the Penang Institute, a state government think tank.

Yet Mahathir’s promise of returning Malaysia to its halcyon days has voters energized and even his erstwhile critics lining up behind him hoping for the nation’s first transition of power.

“Mahathir was a tyrant but he did a lot of good things for Malaysia. At the time, the country was seen on par with South Korea,” says Eric Paulsen, an activist and executive director of Malaysian NGO Lawyers for Liberty.

Under Mahathir, “life was easier, people had jobs, cost of living was not so tough,” says Rosli, a day laborer in Langkawi, where Mahathir is contesting a parliamentary seat.

Here on Langkawi, an island paradise tourists flock to for its white sandy beaches and azure sea, allegiances to Mahathir run deep. He engineered its transformation from a backwater to one of Malaysia’s tourism magnets – a microcosm of the metamorphisis he orchestrated for the nation.

In a fishing village overrun with ruling party flags, Asimah (not her real name) tells TIME it was Mahathir who cleared the jungle, built her neighborhood and provided electricity and running water. As she talks, a construction worker laying sheet-metal roofing yells down, “Mahathir is not just a Langkawi legend, but a Malaysian legend.”

Since its inception as a constituency, Langkawi has been a ruling party stronghold. It is ethnic Malay pockets such as this where the opposition will have to force a groundswell shift away from the ruling party. The Malay vote, some 60% of the total, will ultimately determine the election. The presence of Mahathir, an ethnic nationalist whose patronage created the Malay business class, undercuts the ruling United Malays National Organization’s (UMNO) tired threat that an opposition win will mean ending the Malays special privileges and handing the country over to the Chinese commercial class.

In light of Mahathir’s comeback, even the party’s own people are second-guessing their vote. “Mahathir did everything here. It makes it hard to choose how to vote,” says an UMNO campaign staffer at a rally for Najib.

In stark contrast to the electrified anticipation at Mahathir’s rally, the sitting prime minister’s arrival at a pop-up market in Langkawi on Friday barely turned heads. “The PM was here? I didn’t see him,” said one of the stall workers.

The election is largely seen as referendum on Najib as much as anything else. Independent polling by the Merdeka Center shows support for the prime minister’s party has ebbed among his ethnic Malay bedrock, but he is projected to win the election.

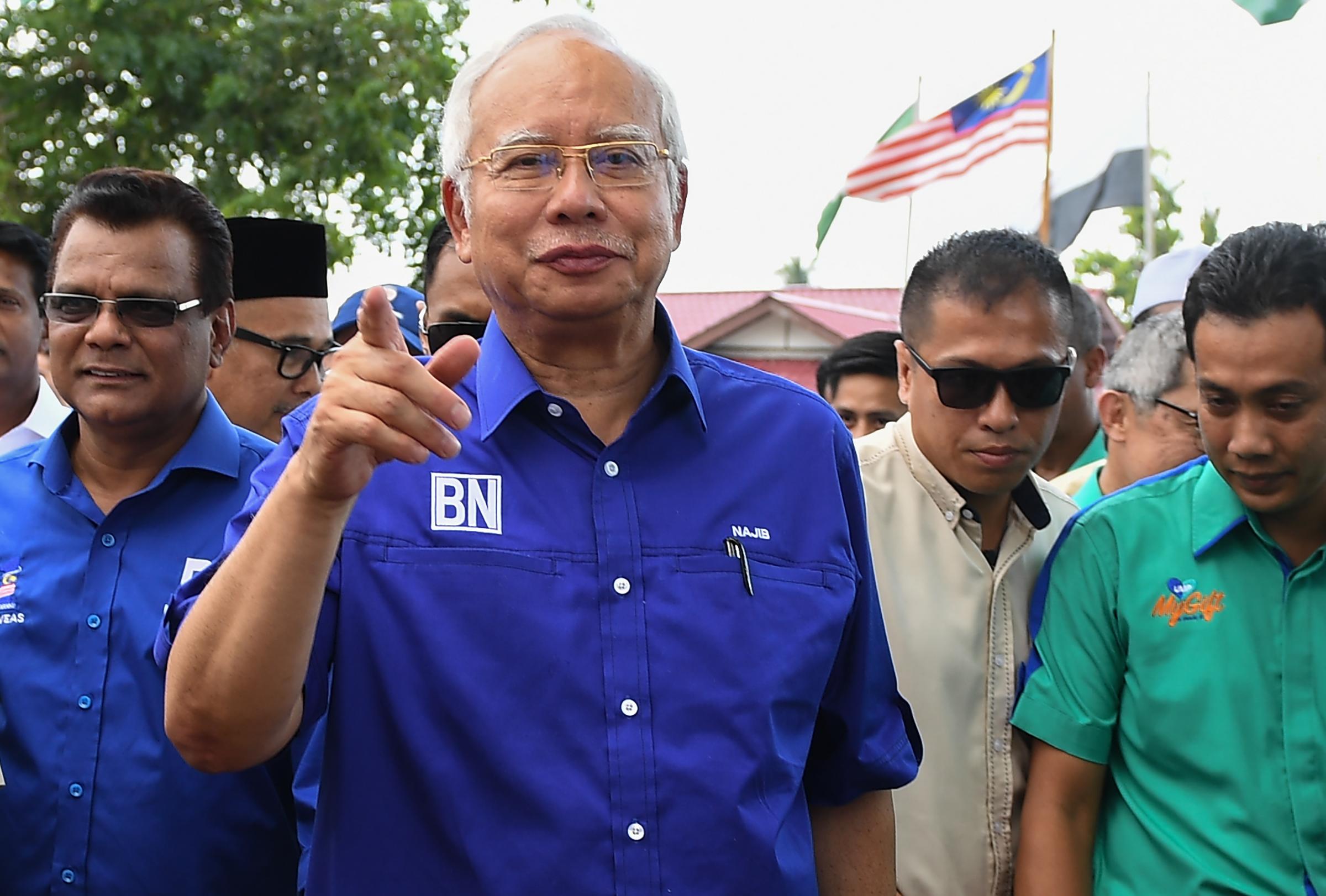

Najib has called on Muslim voters to show “wala”, or loyalty. Should his Barisan Nasional (BN) coalition secure another term, he’s promised an increase in cash handouts to the poor, a hike in the minimum wage, expansion of affordable housing and a possible revision of taxes.

Voters on Langkawi receiving government aid said officials have warned them that supporting the opposition is equivalent to an attempt to “overthrow the regime.”

In order to win, the four-party opposition coalition Pakatan Harapan (Alliance of Hope), will need to overcome an asymmetric system that Mahathir himself helped devise, and once benefited from. There’s the gerrymandering, irregularities with the electoral rolls, the disqualification of six opposition candidates, the de-registration of Mahathir’s new party, Bersatu, and the last-minute move to bar his face from campaign posters resulting in billboards and signs with conspicuous holes cut out. And then there’s the decision to hold the vote mid-week, which the opposition alleges is a ruse to dampen voter turn-out.

“This is one of the dirtiest elections in Malaysia’s history,” says Ambiga Sreenevasan, a human rights advocate and former chair of Bersih, the Coalition for Clean and Fair Elections.

Daim Zainuddin, Malaysia’s former finance minister known as the “oracle” for his uncanny election predictions, says, “If the election was free and fair, the opposition Pakatan Harapan would undoubtedly win.” A week before the polls, Daim defected from the ruling party and has joined Mahathir on the campaign trail.

If Mahathir does win his vendetta and recaptures the post he vacated 15 years ago, he will become the world’s oldest head of government.

Unlikely to fulfill a five-year term, Mahathir is seen as a placeholder for someone else, though how long he plans on retaining power, and who he would relinquish it to, remain matters of debate. “Well, I’m 93-years-old. How long can I last? ” he tells TIME from a seaside bungalow resort in Langkawi. He forecasts a term of “two years, maybe three years.”

“Even if I retire after that, I hope to be able to advise the government on how to handle a lot of issues,” he adds.

In a twist that would do Game of Thrones proud, many see his next-in-line as none other than Anwar Ibrahim, the deputy he groomed only to have him imprisoned for five years on corruption and sodomy charges in 1998.

Yet Mahathir and Anwar — who is behind bars again on a second sodomy charge — have agreed to let their animosities lie. Anwar’s own wife now flanks Mahathir as his would-be deputy.

Defying critics who say he’s too old to be back in politics, Mahathir has taken on a challenging, cross-country campaign schedule. Despite having had two bypass surgeries, he appears more youthful and animated than many of his decades-younger colleagues. In Jerlun, he delivered a scathing and witty rebuke of his opponent without notes or a pause. He commanded the podium with gravitas, standing for the duration of his nearly one hour speech.

“With your support, Malaysia can become one of the most advanced countries in the world again,” Mahathir told the crowd who weathered through the rain to the end of the speech.

Even if he doesn’t win, Mahathir’s comeback could damage Najib, who is seeking a third term. Under his leadership, the ruling coalition lost the popular vote for the first time in 2013.Few see him as sticking around to lead the party if he fails to turn the tide on Wednesday.

Many say this election is Malaysia’s best chance to finally break the one-party dominance uninterrupted since independence in 1957.

“The country cannot keep going in this direction,” says Paulsen, “Or we will become a failed state.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Caitlin Clark Is TIME's 2024 Athlete of the Year

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Laignee Barron / Kedah at Laignee.Barron@time.com