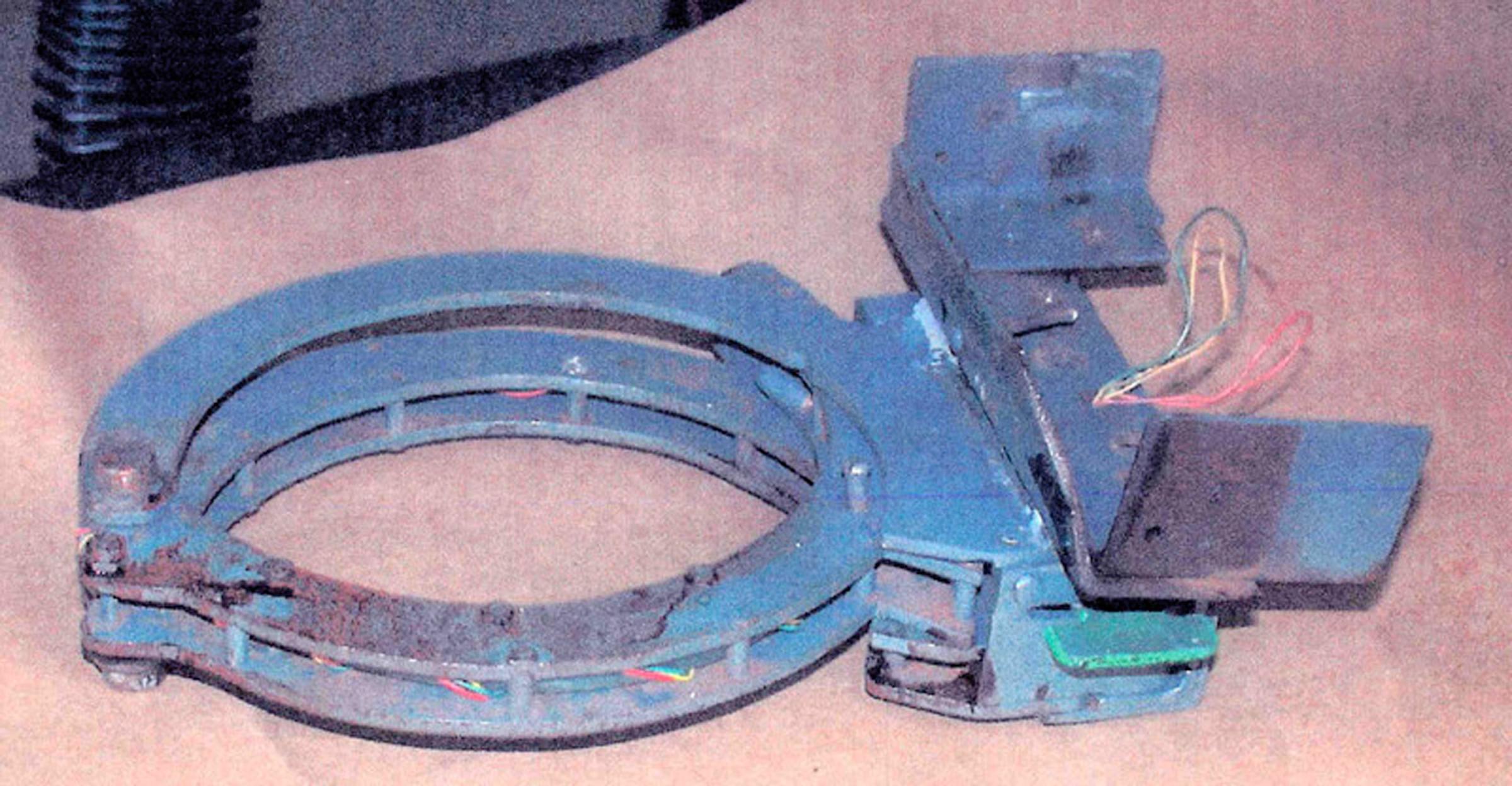

Netflix’s new four-part docuseries Evil Genius: The True Story of America’s Most Diabolical Bank Heist, dives into a high-profile 2003 crime known as the “collar bomb” case. The true crime documentary revisits this so-called “diabolical” plot, which resulted in the death of an on-duty pizza delivery driver, who robbed a PNC Bank in Erie, Pa. with a bomb clamped around his neck. Shortly after the heist, the metal collar device fastened to him exploded, killing him while he sat cross-legged and handcuffed on the ground.

The collar bomb case captivated the country 15 years ago after details emerged that the robber, a 46-year-old local named Brian Wells, appeared to have been a hostage himself, forced to hold up the bank as part of a scavenger hunt he was instructed to complete to save his own life. But at a 2007 news conference that drew the ire of Wells’ family, prosecutors said he was not entirely innocent and had a “limited” role in planning the robbery.

Here’s what to know about the collar bomb case:

What happened?

On Aug. 28, 2003, Wells was working as a pizza deliveryman when he walked into a PNC Bank in Erie, Pa. at about 2:20 p.m. and handed the teller a note demanding $250,000. Authorities said he was holding a loaded homemade shotgun that looked like a walking cane and wearing a T-shirt over an improvised explosive device, which he showed the teller, according to FBI records. About 12 minutes later, Wells left the bank with nearly $9,000 and headed to the McDonald’s next door, where he retrieved another note from under a rock. Shortly after, authorities confronted him at the parking lot of a nearby Eyeglass World retail store. State troopers found Wells inside a parked vehicle and handcuffed him. Authorities said Wells then admitted to being the PNC bank robber. He claimed to have been attacked by a group of black men who he said tied the bomb to his body, court documents show.

The state troopers kept a safe distance as Wells repeatedly warned them that the bomb would blow. “I don’t have a lot of time,” he said, according to a video recording of the encounter. “I’m not lying. It’s going to go off.” The device began to make beeping noises about 20 minutes after Wells was handcuffed, according to the FBI. It beeped for about 10 seconds before it detonated, killing Wells and stunning an audience that had gathered to watch the bizarre situation unfold. “His eyes just got real wide, and then they went to the back of his head. And that was the end of him,” Lamont King, a former Pennsylvania State Police supervisor, says in the documentary.

MORE: 15 of the Most Fascinating True Crime Stories Ever Told

Who was responsible?

In Wells’ car, investigators found pages of detailed instructions on how to find the key and combination codes that would disarm and remove the bomb. The scavenger hunt notes contained language like “we” and “us,” implying there were multiple conspirators involved.

Many leads for potential suspects turned up empty until a local man named William Rothstein tipped off state police to a frozen body in his garage. According to an FBI affidavit, Rothstein said his former fiancée, Marjorie Diehl-Armstrong, had murdered her own boyfriend, James Roden, and stuffed his body in the freezer. Shortly after, authorities arrested Diehl-Armstrong, who later implicated herself and Rothstein in the collar bomb crime. After Diehl-Armstrong was separately convicted for fatally shooting Roden, a fellow inmate with whom she was incarcerated told authorities that Diehl-Armstrong had confessed to killing Roden because he threatened to expose the collar bomb plot to authorities, according to the FBI.

The inmate also said Diehl-Armstrong told her that Rothstein helped build the bomb and “the motive was financial,” according to the FBI affidavit. Another suspect, Kenneth Barnes — a longtime friend of Diehl-Armstrong’s — told authorities that Diehl-Armstrong solicited him to kill Roden and also Diehl-Armstrong’s father because he was giving away money she believed was her inheritance to charities and friends. The FBI documents said Barnes later confessed to punching Wells on the day of the bank heist after Wells got scared and started to run away from the group of conspirators.

In 2007, Diehl-Armstrong and Barnes were indicted for their roles in the deadly bank robbery. At a news conference announcing the indictments, Mary Beth Buchanan, the U.S. Attorney for the Western District of Pennsylvania at the time, said Wells had also been part of the plot. “Unfortunately, our investigation has led to the belief that Brian became involved in a limited role with a group of individuals who planned to rob the PNC Bank,” Buchanan said. “It may be that his role transitioned from that of the planning stages to being an unwilling participant in the scheme.”

Diehl-Armstrong and Barnes were both eventually convicted of conspiracy and armed bank robbery charges.

Where are the collar bomb conspirators now?

Rothstein died of terminal cancer before he could face any charges, according to multiple news reports. Diehl-Armstrong died of natural causes at a Texas prison on April 4, 2017, the Federal Bureau of Prisons said. She had also been diagnosed with cancer, the Erie Times-News reported at the time. On top of her sentence for killing her boyfriend, Diehl-Armstrong, 68, was serving a life sentence after being convicted for her role in the robbery. She was found guilty of using and carrying a firearm during and in relation to a crime of violence, conspiracy to commit armed bank robbery and armed bank robbery, officials said.

In 2008, Barnes was sentenced to 270 months for conspiracy to commit armed bank robbery, using and carrying a firearm during a crime of violence, according to FCI Coleman Low, the federal correctional facility where he’s currently incarcerated in Florida. He is expected to be released in 2027, prison officials said.

Hoopsick, who was never officially deemed a conspirator, could not be reached for comment by TIME. Relatives said she had fallen out of touch with her family, and several phone numbers provided by two of her latest attorneys were either disconnected or belonged to other people.

The Pennsylvania Department of Corrections said Hoopsick had been in the state prison system for theft between May 2012 and July 2014, when she was paroled. In January, Hoopsick was sentenced over a drug charge but paid a $100 fine and did not have to serve time, according to Michael Dejohn, her public defender at the time.

The FBI did not respond to requests for comment, and the U.S. Attorney for the Western District of Pennsylvania declined to discuss the documentary’s findings.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com