John McCain, the Arizona Senator who died on Saturday, lived much of his life in the public political eye — but Americans started to learn about his famous courage at a time he was notably absent.

The saga began 51 years ago. As TIME reported in 1967, North Vietnamese planes had, for the first few years of the war in Vietnam, posed relatively little risk to American pilots. That changed as the pace of war accelerated and the eyes on both sides turned to the skies.

Amid the heated air war, a young Navy aviator — noteworthy at the time mostly because his father was a top admiral — was shot down over Hanoi on Oct. 26, 1967, and captured by the North Vietnamese. His name was John McCain.

And then, like so many of the American troops who were prisoners of war in Vietnam, McCain’s story seemed to pause. Word of what he could be experiencing trickled out in bits, if at all. In 1969, the release of a group of POWs came with reports that, as TIME put it, “the most seriously wounded among the prisoners was Lieut. Commander John S. McCain III, son of the American commander in the Pacific.” According to one former prisoner, word was that McCain had several broken bones and had been in solitary confinement since August of 1968 — more than a year at that point.

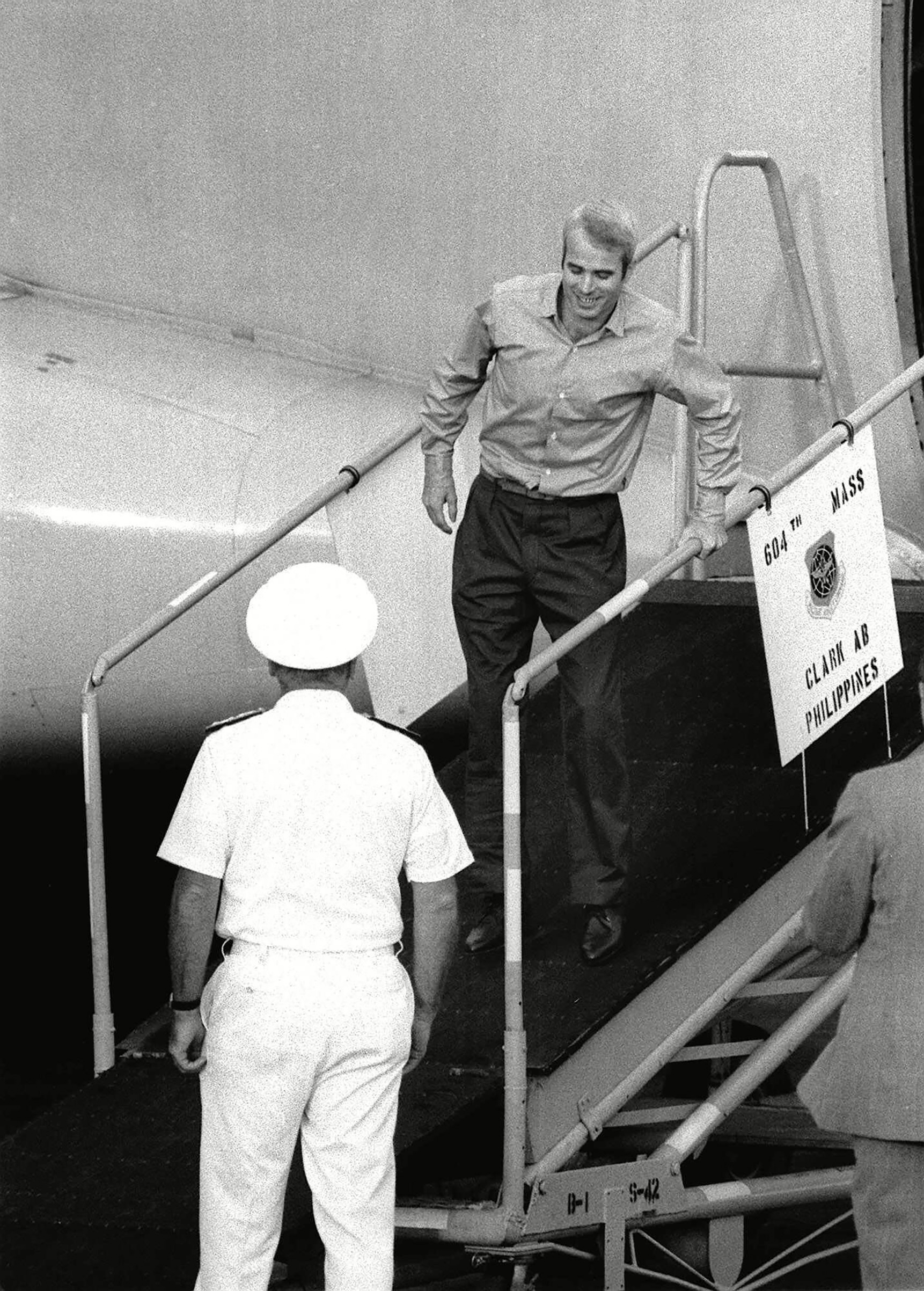

By the time McCain was released in 1973, Americans were learning more about the treatment of prisoners in North Vietnam. The return of almost all of the Vietnam POWs meant that former prisoners could finally tell what they had seen — free from the fear that their comrades would be targets of retribution. “They conceded that treatment had varied for each P.O.W., that conditions had improved remarkably by the fall of 1969, and that high-ranking officers had absorbed the worst of it,” TIME reported.

The details that comprised “the worst of it” were grisly: starvation rations, iron manacles, solitary confinement, the sick left to sit in their own filth. The end goal of such torture was often the extraction of information.

But, along with those reports came word that American prisoners had proved tough to break. Asked to list the names of the men in his squadron, McCain instead listed the offensive line of the Green Bay Packers. When his famous name afforded him a chance to jump the line to go home early, he refused; prisoners were supposed to be released in the order in which they had been taken, and he knew he wasn’t next in line. When his cellmate’s broken arm went untreated, McCain fashioned a cast out of his own bandages.

Read more: TIME’s special edition about the life of John McCain is available now.

All told, he had spent five and a half years as a prisoner, with a substantial amount of that time in solitary confinement. And, though he was self-deprecatingly aware of the irony of becoming well-known as a military man for what he did as a prisoner of war, his story struck a chord with Americans of all political leanings. And McCain, as much as anyone, knew that such a feeling was rare — and something that should not go to waste.

“Until the day I went down, I lived under my father’s shadow,” McCain told TIME in 1978. “Incarceration relieved me of that burden — he couldn’t affect my future there.”

In the decades that followed, he proved that incarceration did more than merely offer the opportunity to make his own name. It shaped his life and gave him an origin story that would sustain the McCain mythology throughout the rest of his time in the military, as well as in the House and the Senate.

“It’s not just that he survived being hung by ropes from two broken arms and beaten senseless; it’s that when his captors learned of his famous father and offered to let him go home, he refused unless they let the rest of the prisoners go as well,” TIME noted in a 1999 cover story about his run for the Republican presidential nomination.

“Such conduct enthralls a generation that aches for heroes and doubts the moral detour it took during the years John McCain was becoming the icon of Duty, Honor and Country.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Lily Rothman at lily.rothman@time.com