It’s been centuries since Earthlings last gave Mars a moment’s peace. From the first time we noticed it hanging in the sky — closer than other worlds, brighter than other worlds, unsettlingly redder than other worlds — we have alternately loved it, feared it and hung our hopes for life in the lonely cosmos on it. That romance is as passionate as ever. There are currently eight active spacecraft orbiting or on the surface of Mars — two of them rovers. On May 5, NASA will launch yet another, the Mars InSight lander, which will be the first ever to drill a probe deep into the Martian subsurface.

The big question — whether there was or is life on the Red Planet — is the one that animates all of this work, and it’s a question that gets a close, smart and readable examination in the new book, Life on Mars: What to Know Before We Go, by David A. Weintraub, professor of astronomy at Vanderbilt University. Weintraub explores the history of our Martian passion, the blunders we’ve made in our pursuit of it — think Percival Lowell’s and Giovanni Schiaparelli’s imaginary canals on the Martian surface— and the progress we’ve made in our genuine understanding of the planet. In a conversation with TIME, he discussed all this and more.

So, why Mars? There are so many other pretty planets in our solar system alone, to say nothing of the trillions of others we now know are out there. Why is Mars the it planet for Earthlings?

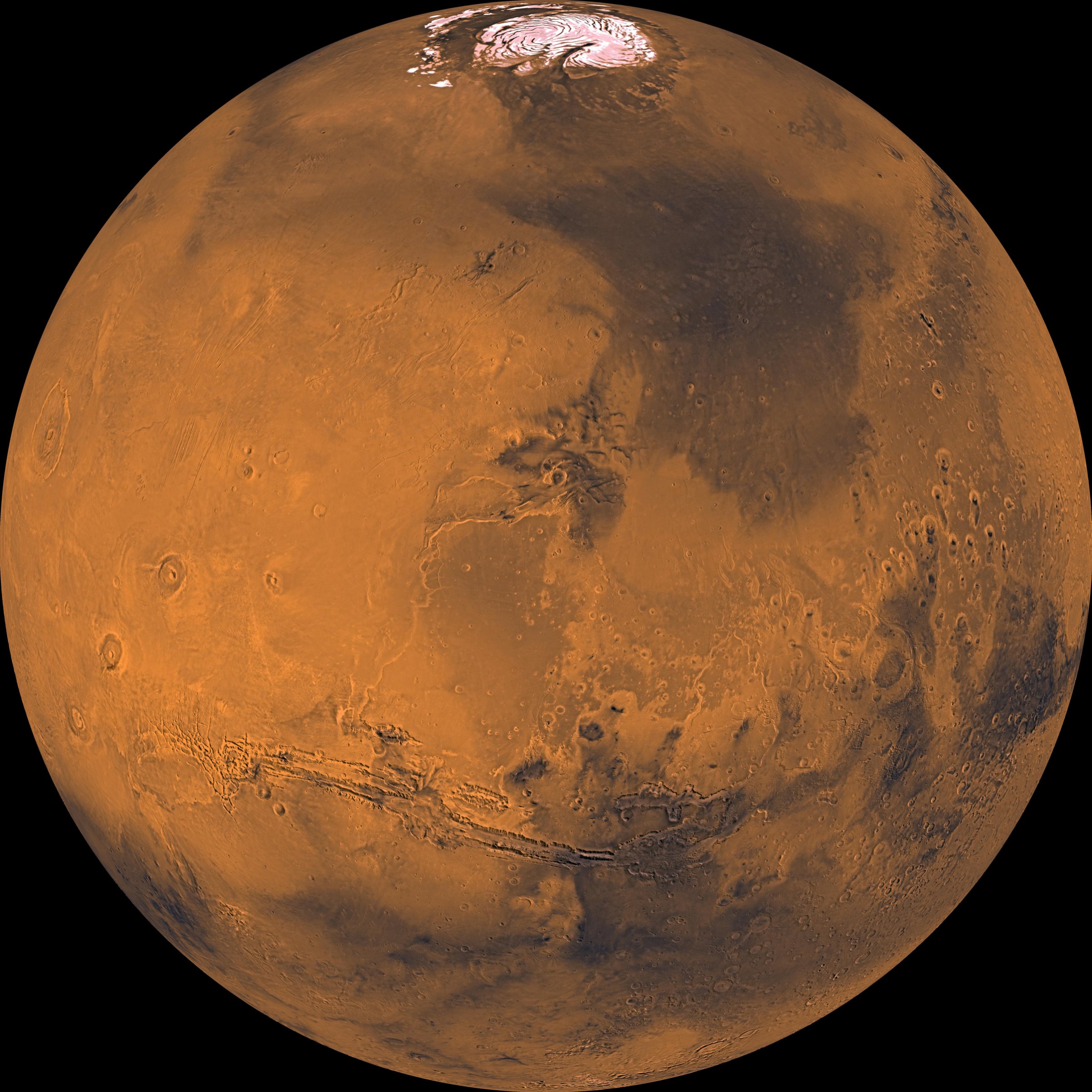

We fell in love with Mars hundreds of years ago by convincing ourselves of its similarity to Earth. Some of that is perfectly reasonable. It has ice caps like Earth, it has seasons, its rotation almost exactly matches Earth’s, it gets a similar amount of sun as Earth and while it’s smaller than Earth, it’s another rocky, terrestrial planet. All of that made it easy for us to tell ourselves that life was likely to have emerged there. What’s more, its proximity to Earth meant that we could one day go and encounter that life.

In your book, you discuss the “Principle of Plenitude,” which is a lovely term, even if it’s not immediately clear what it in the world it means. What is it and how has it influenced our view of Mars?

The idea emerged about 1,500 years ago that God would not waste his creative energy producing a cosmos full of planets without life on them. It takes living things to worship God, so if you’re going to have planets everywhere, you also need to populate them. There’s obviously a very religious origin to the principle of plenitude. We’ve gotten away from that to a degree, but plenitude still influences us powerfully — all we’ve done is couch it in statistics, rather than religion. The chemistry of life is common — hydrogen, oxygen, carbon, water — and we now know how common planets are. If there are so many of them orbiting so many other stars, there should certainly be life on at least some of them.

We’ve misled ourselves in the past into thinking that we had found life on Mars. In the 1970s, there was a lot of excitement when the Viking landers appeared to have detected organic processes, and in the 1990s there was even more buzz when it appeared that bacterial fossils had been found in a Martian meteorite. Both ostensible discoveries turned out to be wrong. And of course there were the non-existent canals. Is our scientific rigor distorted by wishful thinking?

Early on, some of the problem was merely that the telescopes weren’t very good. Also, astronomers were peering through Earth’s atmosphere and then Mars’s atmosphere, which both distort the image. There are dark and light boundaries on the surface of the planet that look sharp; Schiaparelli and later Lowell just convinced themselves that the lines were longer and straighter than they are and that they had to have been made by intelligent beings. We’d still like to see life on Mars, and that influences the kinds of studies we conduct and the kinds of results we’re looking for. But today we take care to determine if what we see is genuine evidence of biology or not.

We know that Mars could have been a contender. It had a thicker atmosphere once, and it had abundant water. So what killed it?

First, I wouldn’t say Mars is dead yet, whereas the moon is dead. Mars still has an atmosphere and it has temperatures that allow it to maintain liquid water on the surface for a little while each year. But Mars does not have an ozone layer and it’s too small to have a magnetic field. The lack of ozone means that ultraviolet energy can penetrate the atmosphere and bust up water molecules into hydrogen and oxygen. The hydrogen bubbles up to the top of the remaining atmosphere and the lack of a magnetic field means that the solar wind can stream past and strip the hydrogen away.

And yet your book says that there’s still a lot of water on Mars — enough to cover the planet to a depth of 69 feet. Isn’t that plenty to give life a chance?

It’s less than it seems. For starters, Mars is only half the diameter of Earth, which means it has a quarter of the surface area, so on an Earth-sized world, that Martian water would reach a depth of only sixteen or seventeen feet. It’s still a lot, but the planet may have lost 80 or 90 percent of the water it once had; what’s left has retreated mostly into the ice caps or underground. But yes, if we could somehow find all that water and melt it and put it on the surface, we would have lots to use when we went there.

Ultimately, life on Mars is a yes or no question. It’s either there or not — at least as microbes, perhaps in those underground water deposits. What’s your best guess?

If I had to bet my house, I’d bet no. As a scientist, though, I want to keep an open mind and betting isn’t a way to do science anyway. That’s why, for a while at least, I want robots to keep going there, keep flipping over rocks and digging cores, and see what they find.

What about elsewhere in the cosmos? Is life easy or is it hard?

I think intelligent life is probably incredibly hard. We know that life existed on Earth 3.8 billion years ago, but it then took two billion years to get to organisms made of two cells or more and a total of three billion after life began before we got to plants and animals. Meteorites have been found with nucleotide bases in them and they make up DNA, and this is the kind of material that would rain down on planets as they grow. So a single cell or a virus might not be hard. I wouldn’t be surprised if we did detect primitive life; I would be surprised if it was intelligent.

One day, humans may finally live on Mars. Would you like to be one of them?

I cannot imagine a more exciting, more life-affirming, more amazing adventure than trying to establish a colony on Mars, trying to place human footprints on another planet for the first time. So, yes, I’d go tomorrow. But only if: a) I knew that the possibility existed for me to come back to Earth to visit and play with my grandchildren — if I one day have any that is — and b) My wife would go with me and c) I knew that the likelihood that I could survive was high — understanding that nothing is guaranteed, even here on Earth — and d) I knew that, to the greatest extent possible, we had already confirmed that Mars had no pre-existing lifeforms so that I was not going to be responsible for wiping out the Martians.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Jeffrey Kluger at jeffrey.kluger@time.com