There was a cheeriness redolent of a family reunion when the leaders of North and South Korea met for denuclearization talks at the peninsula’s demilitarized zone (DMZ) on Friday, shaking hands across the frontier before Kim Jong Un made history by stepping over the raised concrete slab marking the border to become his dynastic regime’s first ever leader to visit the South.

Then Kim, a portly vision of black in a Mao-style suit and horn-rimmed glasses, invited South Korean President Moon Jae-in to hop back across to North Korea, the land from where his refugee parents fled to the South on an U.N. supply ship during the 1950-53 Korean War. The two leaders then crossed once again to the South, hand-in-hand, before sitting down to negotiations at the DMZ’s Peace House, emerging in the twilight to declare that conflict was “over” and both would work toward the “complete denuclearization of the Korean peninsula.”

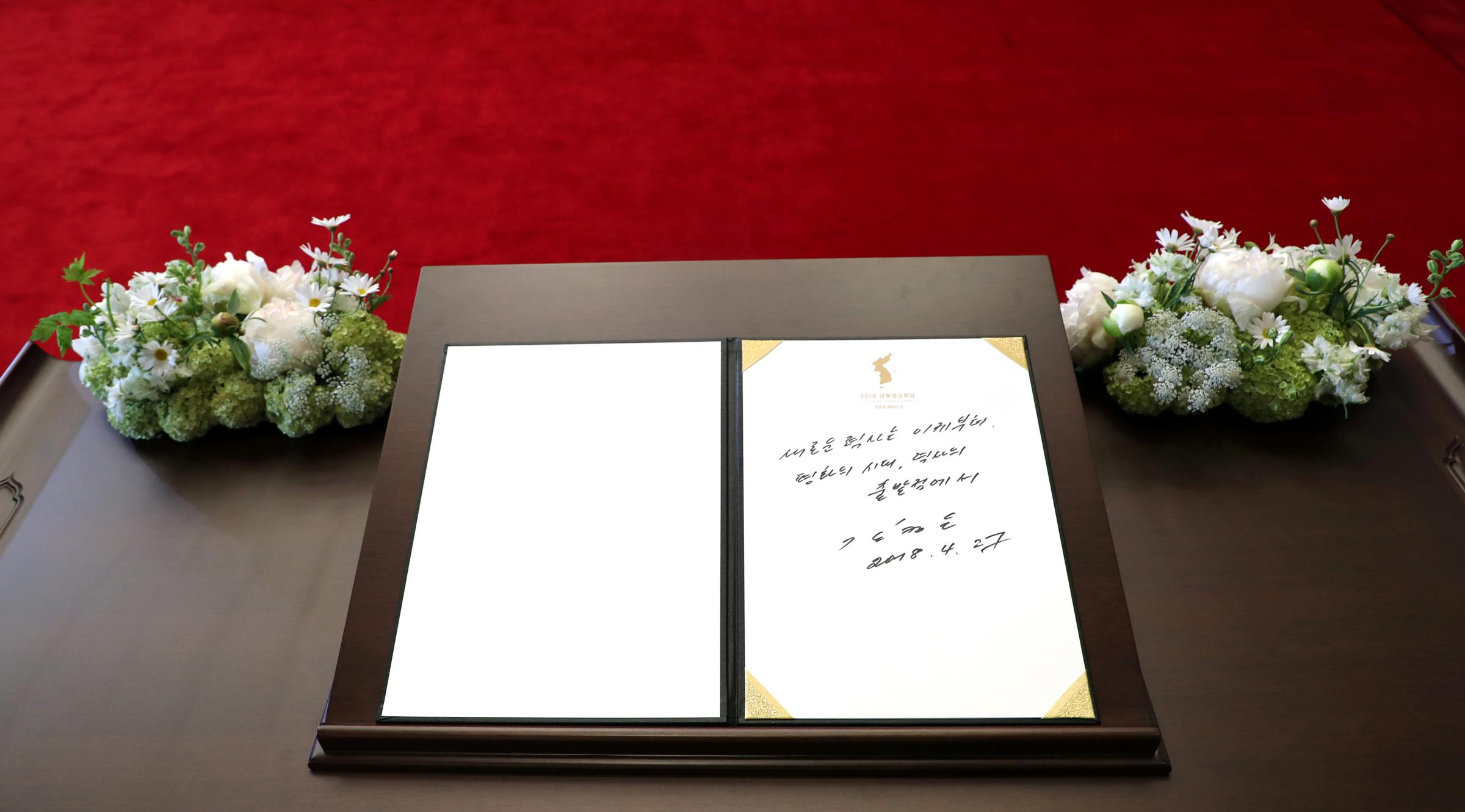

“There will be no more war on the Korean peninsula and thus a new era of peace has begun,” said a joint statement signed following the talks. Kim Jong Un said the Koreas are “linked by blood as a family and compatriots who cannot live separately.”

For Moon, reaching this point has been a lifelong ambition. He helped broker the last summit between the leaders of North and South, 11 years ago, when he was chief of staff to then South Korean President Roh Moo-hyun. Now Moon has the top job and is charged with persuading Kim to give up his nuclear weapons and a hawkish Donald Trump administration to invest the time and energy needed to ink a deal acceptable to all parties. A White House statement expressed hope “that talks will achieve progress toward a future of peace and prosperity for the entire Korean Peninsula,” and that Trump was looking forward to meeting Kim himself in coming weeks.

As expected, the summit was meticulously choreographed and full of symbolism. An honor guard of Korean soldiers in bright traditional war robes welcomed the leaders, during which Kim appeared slightly uneasy, panting heavily. But he appeared in fine fettle once the leaders and their traveling delegations — seven from South Korea; nine from the North, including Kim’s influential sister — sat down for discussions on chairs marked with a map of a united Korea. Kim even ribbed Moon about North Korean noodles being popular in the South. He also said he was “willing to go to [South Korea’s Presidential] Blue House at any time” if invited, according to Moon’s spokesman.

But if the symbolism was laid on a little thick, it was perhaps because substantive outcomes were limited. Both sides agreed to high level military talks next month, to resume reunions of families separated by the Korean War and for Moon to visit Pyongyang in the autumn. But North Korea is subject to strict new U.N. sanctions following its escalating missile and nuclear tests, meaning Moon alone has little power to offer economic inducements.

Even a formal end to the Korean War, which Moon and Kim announced Friday, rings hollow unless the U.S. was also party. (The nations technically remain at war as an armistice rather than peace treaty was signed.) The two leaders said they will work towards signing a peace treaty this year on the 65th anniversary of the armistice — July 27 — which was originally signed between North Korea, China and the U.S. And no specifics were revealed for exactly how denuclearization would occur.

Read more: What Kim Jong Un Really Wants From President Trump

“Serious discussion about denuclearization is simply impossible because this is not so much an issue of South Korea, but rather an issue of the United States,” Andrei Lankov, professor of Korean studies at Seoul’s Kookmin University, told South Korea’s Arirang TV. “South Korea should push the United States towards accepting a compromise.”

Before the summit, Kim had already promised to end missile launches and dismantle his Punggye-ri nuclear testing site. During discussions Friday, he joked to Moon that he “would not interrupt your early morning sleep anymore,” referring to his typically daybreak weapons tests. Moon and Kim appeared to be genuinely connecting; they enjoyed a lengthy chat while sitting alone on a blue footbridge following a tree-planting ceremony, with nearby microphones only picking up the tweeting birds of the surrounds.

But few believe North Korea will truly dispense of its nuclear arsenal after decades spent honing it. Late last year, the regime tested an intercontinental ballistic missile (ICMB) it claims could strike anywhere in the continental U.S. “Let’s take denuclearization off the table — isn’t going to happen,” says Christopher Green, a senior researcher on the Korean Peninsula for the International Crisis Group. “But North Korea may be attempting to make a serious change of direction whilst also retaining a nuclear weapon.”

While the lives of the 25 million ordinary North Koreas are largely irrelevant for Kim, he does rely on the backing of 2 million-odd elites, who mainly live in Pyongyang and are growing increasingly dissatisfied with the direction of the nation, according to South Korean intelligence. “They’re not sure that the state will survive, but more than that they don’t feel like their children have too many opportunities for the future,” says Green.

Satisfying Trump enough to ease the sanctions and allow North Korea to prosper will not be easy. While China and the U.S. agreed last year that denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula should be “complete, verifiable and irreversible,” North Korea likely has a different interpretation — one “to revolve around decreasing the saliency of nuclear and missile tests in its diplomacy, rather than the complete, verifiable and irreversible disarmament desired by the West,” writes Karl Dewey, a chemical, biological, radiological and nuclear defense analyst for Jane’s by IHS Markit.

Kim’s announcement of the dismantlement of Punggye-ri has been tempered by reports from Chinese geologists that it had already collapsed, possibly resulting in significant radiation poisoning. At any rate, its closure could simply mean North Korean engineers are satisfied with the design of their nuclear devices and thus no longer need to test, or that a second facility could be set up were further refinement required.

Read more: What Would Korean Reunification Look Like? Five Glaring Problems to Overcome

The challenge facing Moon is to keep the Trump administration engaged, even if the goalposts shift significantly from total disarmament. Trump’s hawkish new Secretary of State Mike Pompeo and National Security Adviser John Bolton have repeatedly insisted that military options remain on the table, despite the utter devastation that could be wrought on South Korea and Japan by Pyongyang’s conventional, chemical and nuclear retaliation. Low-hanging fruit may be for Kim to return the three Americans his regime currently holds captive, thus providing Trump with a small but ego-boosting victory.

Still, Lankov worries that the Trump-Kim summit “might not happen or might end in disaster,” because “there is always a possibility that at the last moment President Trump will listen to some of his advisers who will tell him nothing but full and immediate nuclear denuclearization is acceptable.”

Moon entertaining Kim was the easy part. Keeping Trump ameliorable and on message at the next summit is when the true work will begin.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Caitlin Clark Is TIME's 2024 Athlete of the Year

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Charlie Campbell at charlie.campbell@time.com