North Korean leader Kim Jong Un and South Korean President Moon Jae-in may be meeting each other for the first time on Friday, but there’s a sense of déjà vu in the air.

They’re meeting at Panmunjom in the Demilitarized Zone on the border of the two countries, the same place where an armistice was signed — by U.S. Army Lt. Gen. William K. Harrison Jr. of the United Nations Command Delegation and North Korean General Nam Il, who also represented China — on July 27, 1953, putting an end to the roughly three years of fighting of the 1950-1953 Korean War.

But the armistice was a ceasefire, not a permanent peace treaty. That means the countries are technically still at war, in a decades-long “conflict without hostilities,” says historian Charles K. Armstrong, a Korean Studies specialist. That’s a fact about which U.S. President Donald Trump expressed surprise this month. “People don’t realize the Korean War has not ended,” he said.

So why wasn’t a permanent peace treaty signed back then? And why wasn’t South Korea on board in the first place?

“The top commanders, like everyone else, were glad that the bloodshed was ended, but they took no pride in their achievement, and they felt no satisfaction in the armistice they were ordered to sign,” TIME reported the week after the signing. “They knew the argument that in this war freedom had been defended and aggression repelled, but, cabled TIME Correspondent Dwight Martin, ‘they all seem concerned that some day they will be called on to explain why they signed the present armistice. Several I’ve talked to specifically think in terms of investigating committees demanding to know whether it is a fact that they sold out Korea. They frankly admit that complex justifications and explanations, currently acceptable, may look pretty lame in a year or so.'” (In fact, there were fears of a nuclear war then as now.)

South Korea didn’t even sign the armistice, though the nation recently confirmed that it has discussed signing a peace treaty with North Korea.

Even so, the parties who signed the armistice certainly didn’t plan for the conflict to remain unresolved for more than half a century. They planned to reach a permanent peace agreement the following year, at a conference in Geneva. In fact, the promise of such a conference — perhaps tellingly — was a crucial step in allowing both sides to agree to sign the armistice agreement even without having all their concerns addressed at the time.

That conference, which also addressed a number of other global issues, convened precisely 64 years ago Thursday, on April 26, 1954. But, when it came time to set the final terms there, leaders couldn’t agree on the best path forward.

“The idea of the Geneva conference was that there would be a new unified Korean government established after a new election, but [delegates] couldn’t agree on the process of how that would happen,” says Armstrong. “So the Geneva conference collapsed and we’ve been in the same situation ever since. There have been periodic discussions, but the situation of conflict has never been resolved.”

South Korea didn’t sign the armistice because its President, Syngman Rhee, thought that “the U.S. should have done more to extend South Korea’s control over the peninsula,” says Armstrong. Another obstacle was America’s refusal to recognize the People’s Republic of China as a legitimate government, symbolized by Secretary of State John Foster Dulles refusing to shake hands with Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai during the Geneva conference.

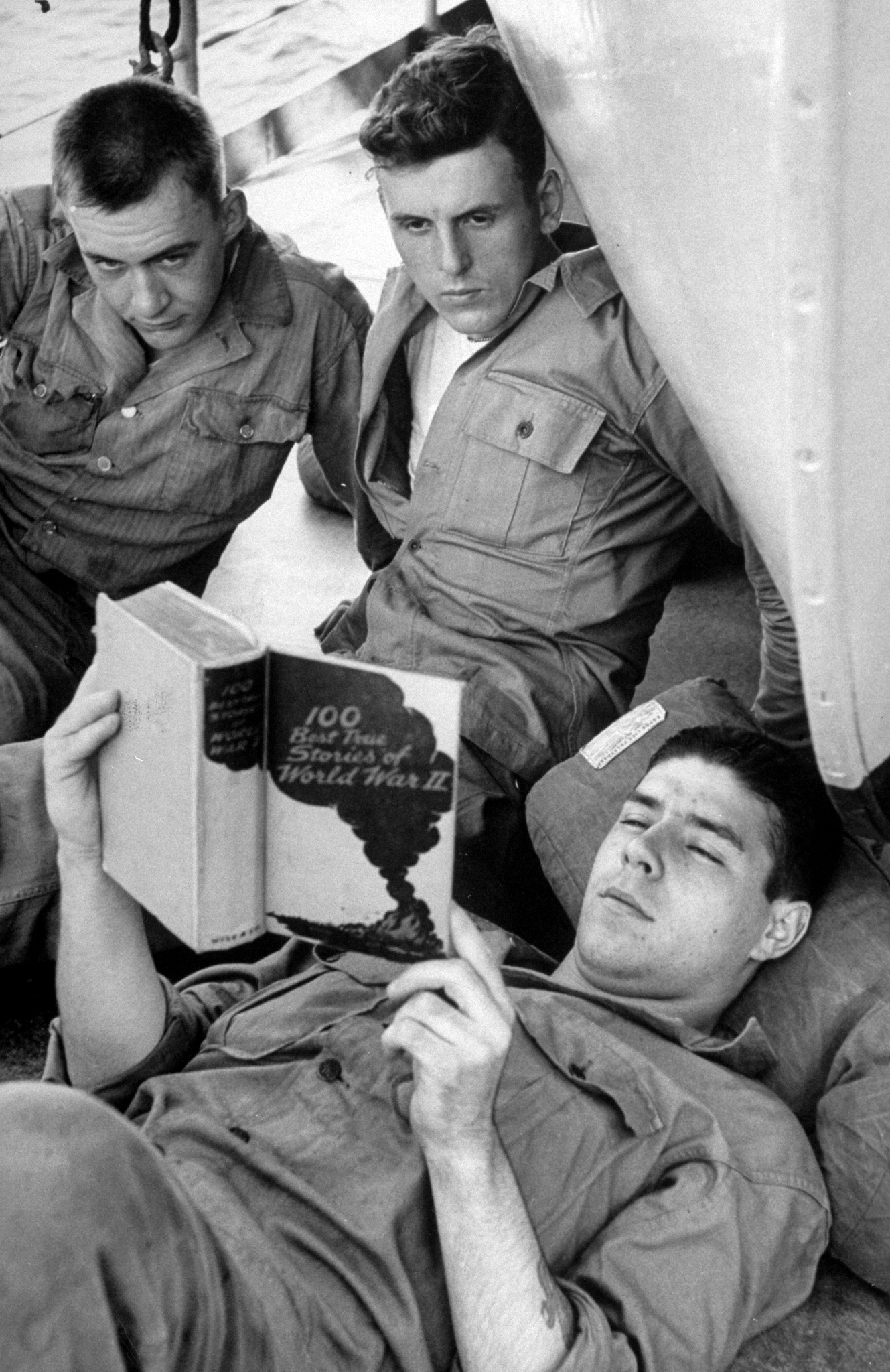

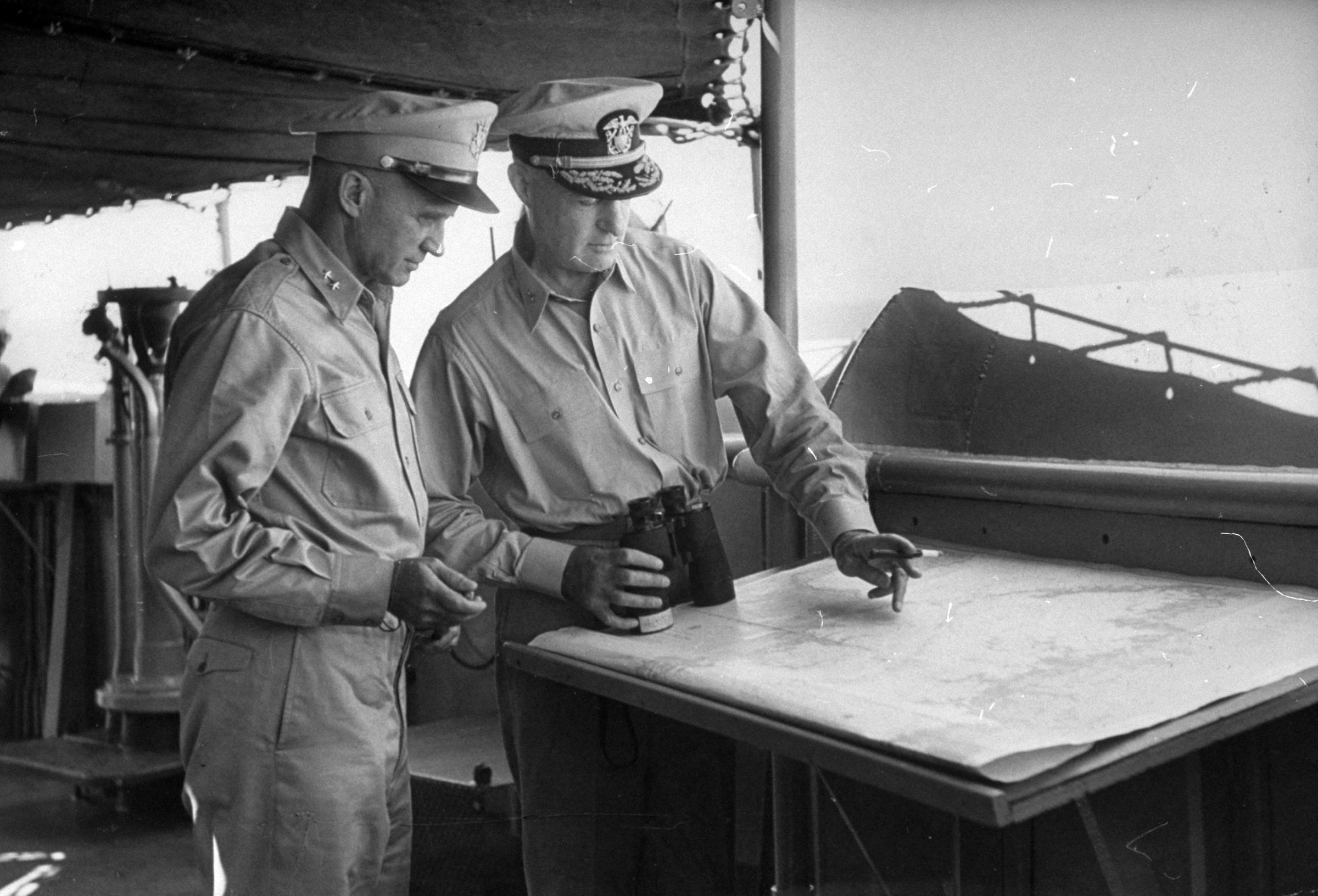

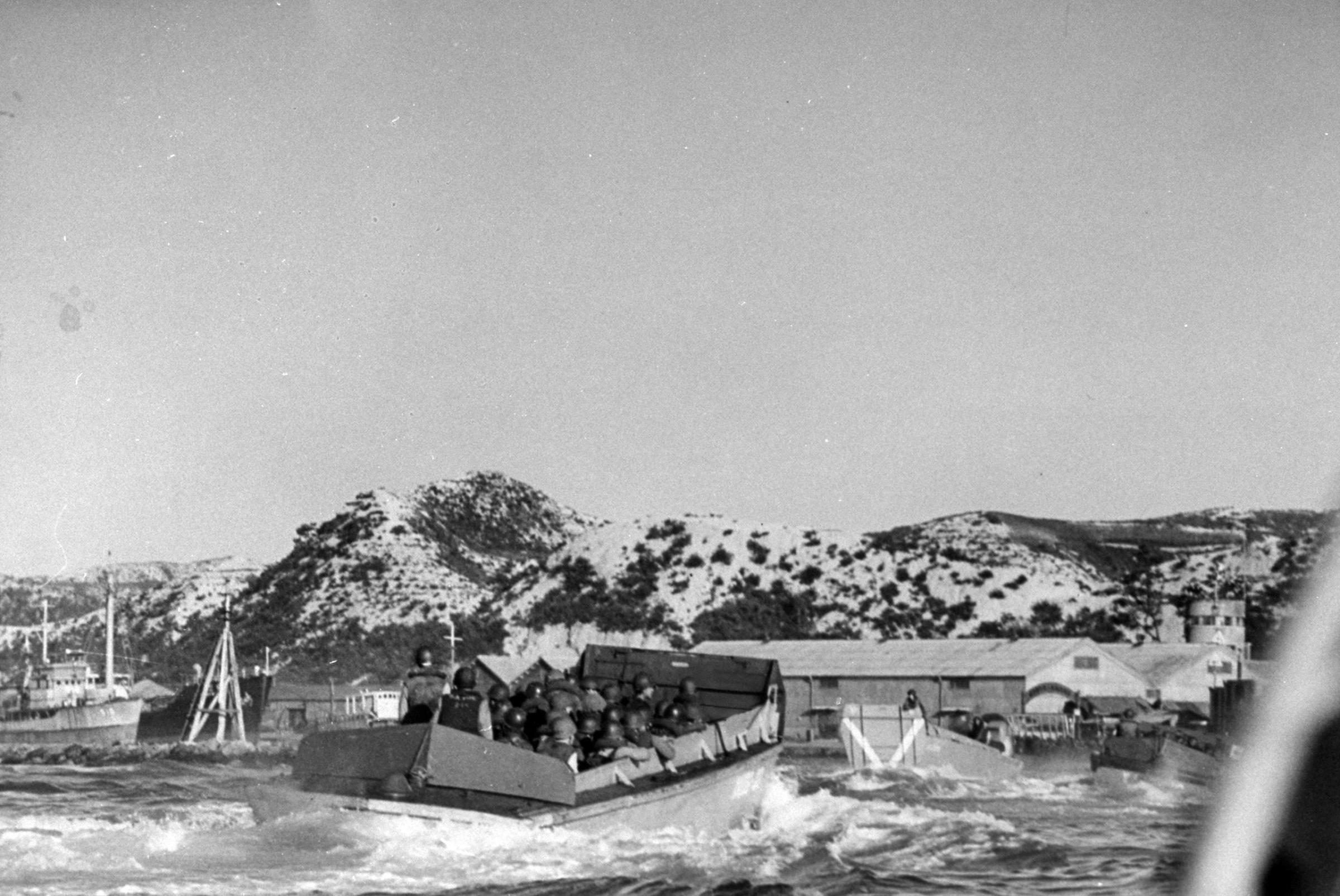

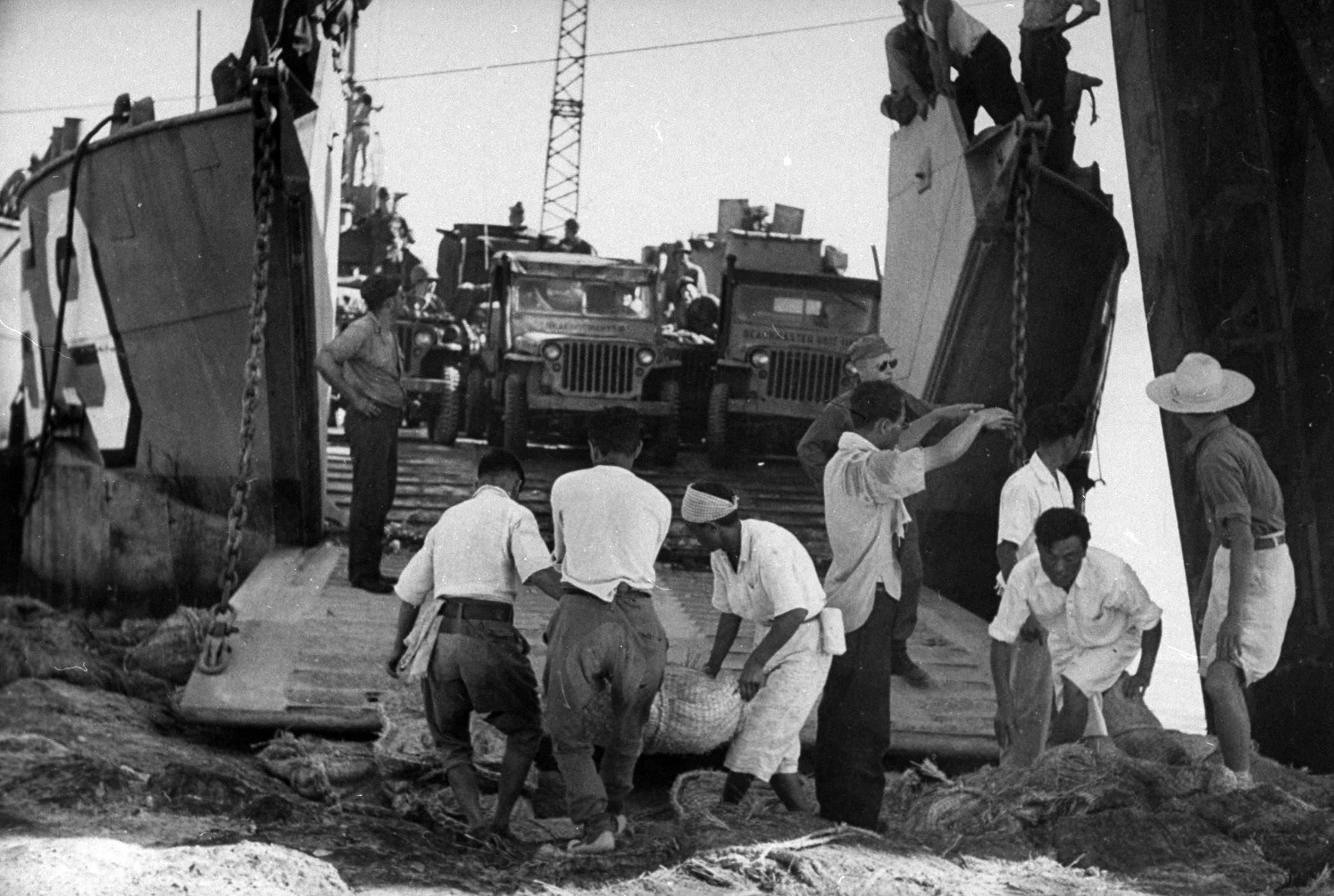

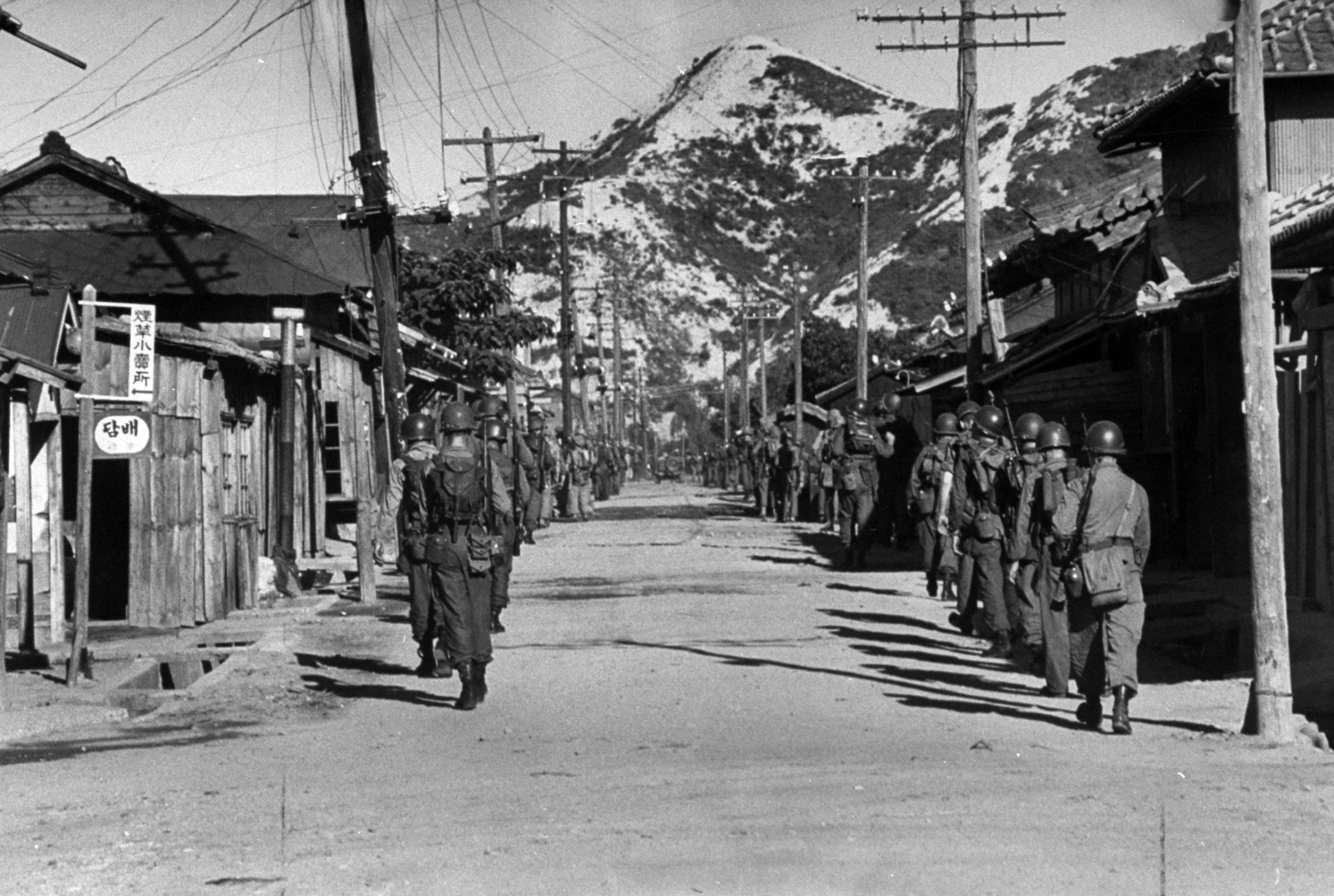

See Photos from the Early Days of the Korean War

North Korea and South Korea later signed a pact promising to refrain from aggression. In Dec. 1991, in keeping with the peacetime spirit of the end of the Cold War and the collapse of the Soviet Union, the two sides promised to work towards reconciliation, following a U.S. pledge to withdraw nukes from South Korea. The U.S. announced it would suspend joint military exercises with South Korea a month later. The pact wasn’t very effective, but “that agreement also hasn’t been abandoned either,” Armstrong adds. “But then in 1992 the U.S. began to accuse North Korea of possibly developing a secret nuclear weapons program, so we didn’t get very far after that.”

The armistice has always been on shaky ground. “There have been numerous violations of the armistice agreement since 1953, and things seemed to escalate around 2010,” says Armstrong. He points to the sinking of the warship Cheonan, which killed 46 sailors in March of 2010 and for which South Korea blames the North, and the North firing artillery shells onto the South Korean island of Yeonpyeong in November of the same year, killing two marines and two construction workers and wounding more than a dozen others. In 2013, North Korea even declared the armistice invalid.

“The line between a state of conflict and active hostilities is pretty thin, and there isn’t much to restrain either side from going to war if that’s what they wanted to do,” says Armstrong. “I don’t expect a grand bargain, but I feel there’s a lot of potential we haven’t seen in decades. All three sides seem really keen on making something work. We’ll see what happens.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Olivia B. Waxman at olivia.waxman@time.com