The iconic line has become so familiar that it might be hard to imagine it any other way: as the first man on the moon put it, his achievement was “one small step for man.”

But what if the first human being on the lunar surface had been a woman? That’s a central question asked by the Netflix documentary Mercury 13, directed by David Sington and Heather Walsh, premiering Friday — and, say the filmmakers, a question that’s still worth asking even decades after the last moon landing.

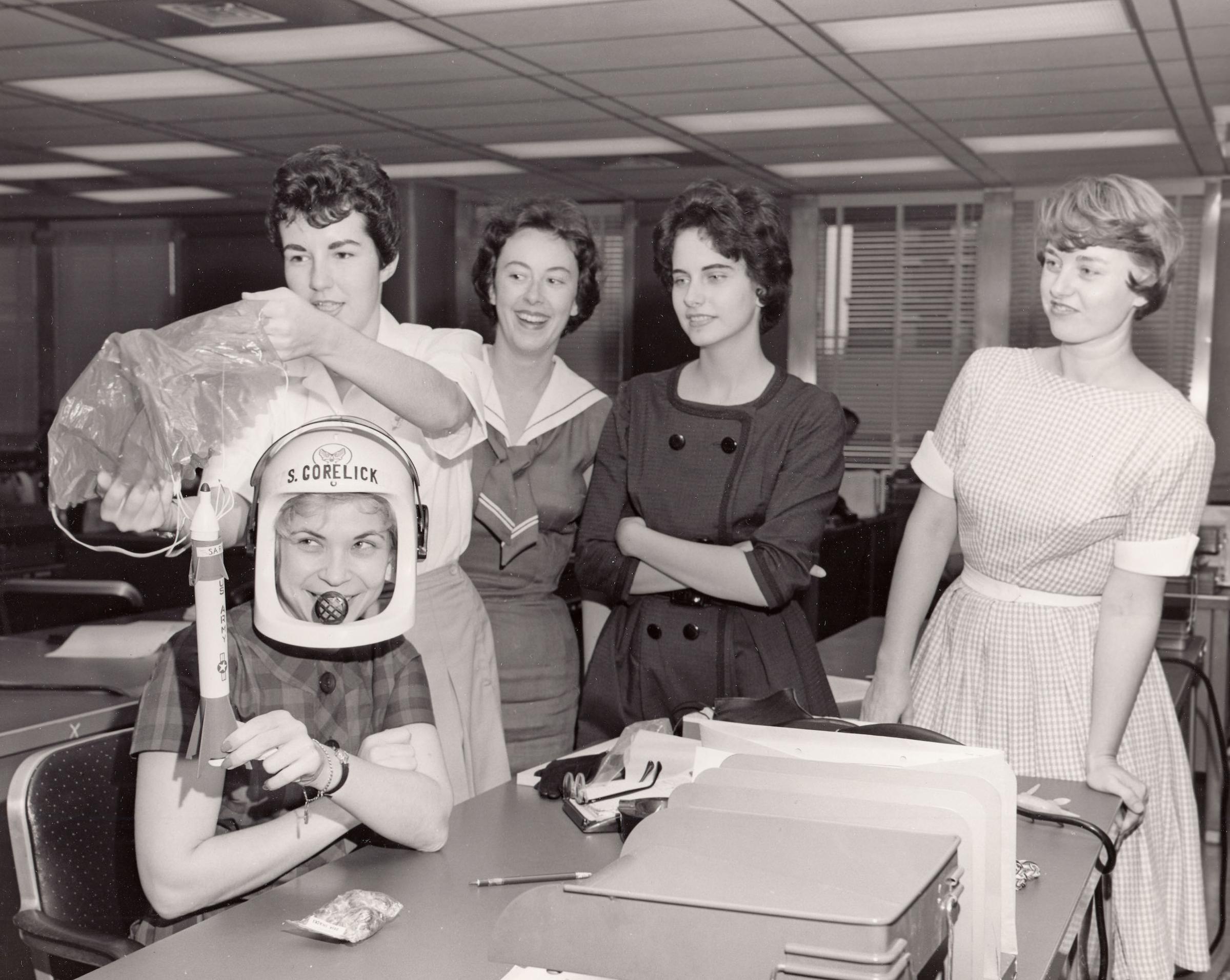

The “13” in question were a group of experienced female pilots — Jerrie Cobb, Janey Hart, Jan Dietrich, Marion Dietrich, Rhea Hurrle, Irene Leverton, Bernice Steadman, Jean Hixson, Gene Nora Stumbough, Jerri Sloan, Myrtle Cagle, Sarah Lee Gorelick and Mary Wallace Funk — who in the early 1960s were invited by Dr. Randolph Lovelace, who had also been involved in testing male pilots for the same reason, to take the tests he had given to the Project Mercury astronauts. (Though she later spoke out against pushing to include women, the idea was initially helped along by famed female pilot Jackie Cochran, and by her funding.) Cobb was the first woman to undergo the testing, and after she passed the test the other women were invited to participate.

As TIME explained in 1960, Cobb underwent “a brutal battery of 75 separate physical and psychological tests” and by passing demonstrated that women, with their lower body mass, “may be better equipped than men for existing in space.” TIME dubbed her “the first astronautrix.”

Though the women initially kept quiet about what was going on, by mid-1960 outlets such as LIFE magazine were covering the story excitedly. As TIME later explained in a 2003 review of Martha Ackmann’s book The Mercury 13, “the macho culture of the space program was too entrenched to accommodate them. Vice President Lyndon Johnson scribbled on a memo about the initiative, ‘Let’s stop this now!’ — and without much fanfare, it was stopped.”

But to the women at the heart of the program, the order to end it was an outrage.

Not only did a few of them testify before Congress in an attempt to be allowed to shoot for the moon, but many of them also continued to lead lives centered around flight, even after their mission was denied.

The fuss the women made about being excluded is key, filmmaker Sington says. For one thing, it gives the narrative an arc. “I was worried that it was a non-story,” he says, “in that it was a story about something that didn’t happen, which is hard to make a movie about.” Walsh says she doesn’t know why the story of the Mercury 13 isn’t better known, but Sington guesses it’s partially related to the narrative difficulties of retelling the story. The women’s anger also prompts viewers to question their assumptions.

That was a feeling that Sington had experienced personally: he had previously worked on a different project about the Apollo program, and says he never questioned the fact of the astronauts’ gender. “The fact that they might have been women never entered my mind,” he says. “But as I began researching this story I realized that wasn’t ‘natural,’ it was a choice that had been made.”

That was precisely the point that Jerrie Cobb and Janey Hart (whose husband was Sen. Philip Hart) made when they testified before the House Special Subcommittee on the Selection of Astronauts on July 17, 1962.

As Cobb told the committee, “we women pilots who want to be part of the research and participation in space exploration are not trying to join a battle of the sexes… We seek, only, a place in our Nation’s space future without discrimination.” There were women on the Mayflower and on the covered wagons that headed west, she added, so why should there not be women in the next phase of American exploration?

Hart spoke next, and elaborated on the point. Here’s how she made the case that the U.S. should send women to space:

It will perhaps come as no surprise to you that I strongly believe women should have a role in space research. In fact, it is inconceivable to me that the world of outer space should be restricted to men only, like some sort of stag club.

I am not arguing that women be admitted to space merely so that they won’t feel discriminated against. I am arguing that they be admitted because they have a very real contribution to make.

Now, no woman can get up and seriously discuss a subject like this without being painfully aware that her talk is going to inspire a lot of condescending little smiles and mildly humorous winks.

But happily for the Nation, there have always been men, men like the members of the committee, who have helped women succeed in roles that they were previously thought incapable of handling.

A hundred years ago, it was quite inconceivable that women should serve as hospital attendants. Their essentially frail and emotional structure, it was argued, could never stand the horrors of a military dressing station.

Most of them would faint at the first bloody bandage. They wouldn’t be able to keep the records straight. And anyway, it was somehow indecent for a woman to be among all those soldiers, wounded or not.

Well, the rest of the story is altogether familiar to you. The women were insistent. There was a shortage of men to do the job. And finally it was agreed to allow some women to try it provided they were middle aged and ugly—ugly women presumably having more strength of character.

I submit, Mr. Chairman, that a woman in space today is no more preposterous than a woman in a field hospital 100 years ago. And I further submit that the venture would be equally successful, although this time there should be a more realistic list of qualifications for the candidates to meet.

I wonder if anyone has ever reflected on the great waste of talent resulting from the belated recognition of women’s ability to heal.

…I correspond regularly with several college coeds who are in the top 10 percent of their class. They are science students and is there anyone here today who will argue that our Nation doesn’t need scientists in practically unlimited numbers?

Yet many times I sense a tone of discouragement in their letters. They see so many obstacles to the realization of their hopes of a scientific career.

It is a known fact, for example, that in spite of population growth and acute need, there are fewer engineering students graduating now than 10 years ago. So why must we handicap ourselves with the idea that every woman’s place is in the kitchen despite what her talents and capabilities might be?

Now, I, like most women, have been blessed with a very happy marriage. I have eight children, four boys and four girls, a demonstration, I think, of the impartiality that I believe should be accorded the sexes.

But equality in numbers is not enough. I should hope that they will also have equality of opportunity to use their minds and talents where they will make the greatest contribution.

Despite their pleas, the women were still shut out of the space program. The Soviets beat the U.S. at this particular space race, sending Lieut. Valentina Vladimirovna Tereshkova into orbit in 1963. Sally Ride became the first U.S. woman in space in 1983, more than two decades after Hart testified — but, even 35 years after that milestone, Hart’s testimony is still poignant.

Just as the Mercury 13 women unsuccessfully tried to convince those running the space program to question their assumptions, says David Sington, their story is a reminder to question other assumptions about gender.

“Once you realize those are choices,” he says, “you can make other choices.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Lily Rothman at lily.rothman@time.com