Barbara Bush was as grounded as any First Lady, a down-to-earth realist planted firmly between two high-flying stars: Nancy Reagan of the rail-thin coiffed good looks, rarely seen children, and adoring gaze; and Hillary Rodham Clinton, the two-for-the-price-of-one lawyer who let it be known she wouldn’t be staying home and baking cookies. But she proved to be a national force, worth every penny we didn’t pay her.

Inside the White House of her husband George H. W. Bush, the country’s 41st president, she had her own signatures: an acerbic wit, an outgoing personality, and the intimidating raised eyebrow that froze those who worked for him. She didn’t have an office in the West Wing or attend Cabinet meetings, but as chief of staff Andy Card remembers, her presence was everywhere — in the speech that came back in the morning better for her edits, the shots she took that the president didn’t have to, the fortress she built around him that gave him the strength to do the job. Skeptical where he was trusting and as outspoken as he was diplomatic, she had his back at every turn: if you slighted him, you would answer to her.

For the country, she offered something else. She never promised us a Rose Garden, photo-ready perfection, or perfection at all. She was honest about her size (14), her hair (white since she gave up dying it in her 30s), her weight (always a few pounds over the ideal) and her pearls ($90 fakes). But there wasn’t much else that was false about her. Her wardrobe ran to exercise clothes when she had no intention of doing more than walking Millie, her English spaniel and co-author of their best selling book. She didn’t play the designer game until pushed into flogging for Seventh Avenue when she became Second Lady. When I interviewed her for her a TIME cover story as she prepared to move to the White House from the Vice President’s mansion after her husband’s 1988 presidential win, she acknowledged that she’d gotten away with murder — advising Nancy Reagan to replace the East Room china one plate at a time, suggesting that her husband strip down to disprove rumors that he was wounded during a tryst, calling Geraldine Ferraro a word that rhymes with rich — but that she would henceforth be more careful about the words coming out of her mouth, adding, after a pause, “slightly.”

Read more: ‘Grit & Grace, Brains & Beauty.’ Presidents From Trump to Carter Honor Barbara Bush’s Legacy

As she aged, America got more of the same from the only woman since Abigail Adams to be the wife of one president and mother to another (George W. Bush, or 43 as he became known). And if it weren’t for a tsunami named Donald Trump, she might have made history as the mother of yet one more. In South Carolina in 2016, she joined the one-time GOP-favorite, former Florida Governor Jeb Bush, whom she famously said was the son she had expected to be the president in the next generation. By then, Jeb’s was likely a losing cause. Already ill, she took the trip anyway, cheering him on, chin pointed upward, eyes shining, smile full. Her husband’s reelection loss to Bill Clinton in 1992 was heartbreaking, she wrote, but there is no wound so stinging as those endured by a child.

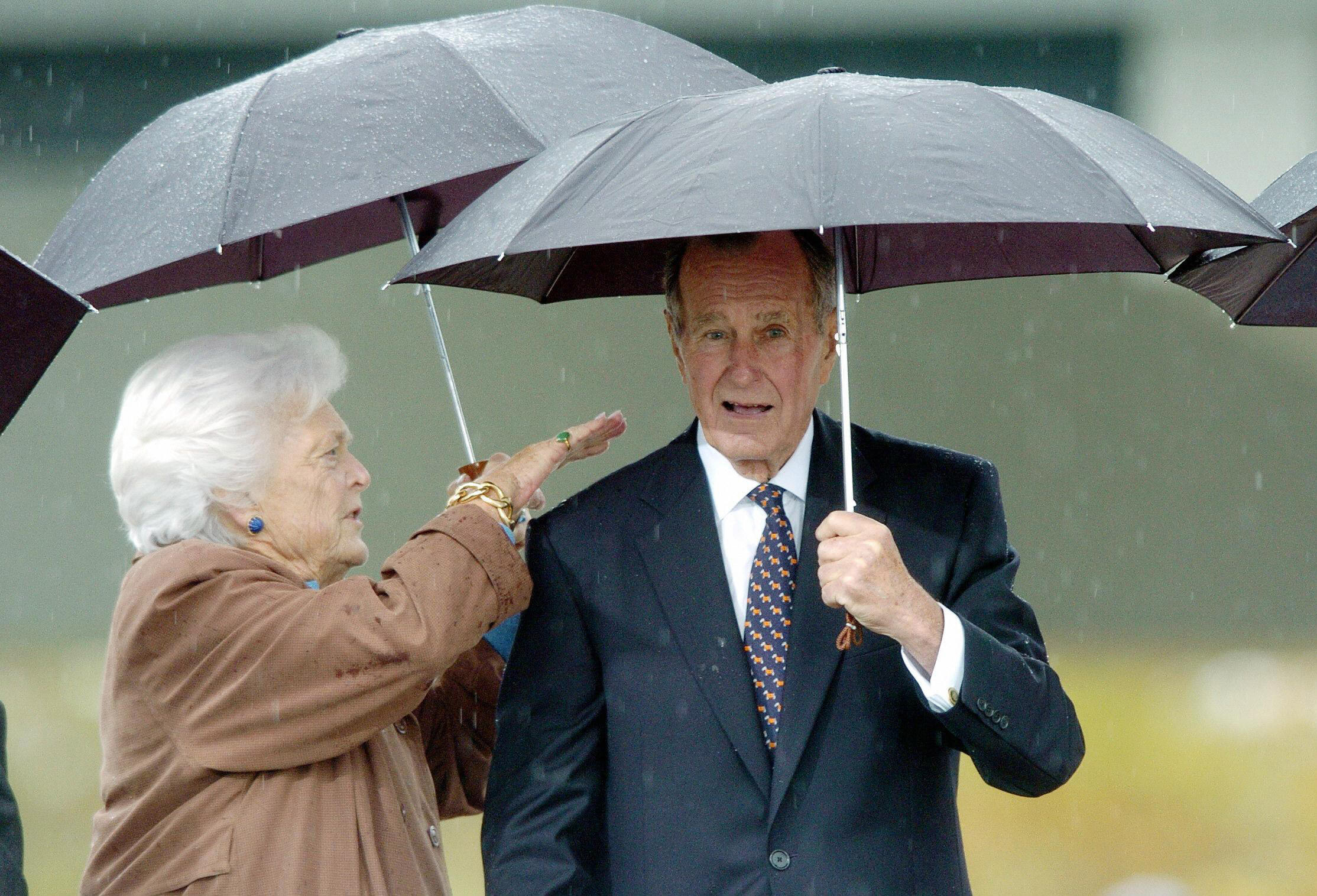

That would be her final campaign. Barbara Bush died at age 92 on April 17, 2018. She left this world the way we all want to, peacefully at home, free of code blues and intubations, surrounded by family and her husband, George H. W. Bush, whom she married in 1945. They survived 73 years of marriage, a long wartime separation, the death of a child, 30 moves, and the ups and down of leading a very public life with all the satisfactions and disappointments that come with it. In her class note for her alumnae magazine last spring, Bush wrote that she’d gotten so many new body parts she was hardly recognizable but life was good. “I’m still old,” she wrote, “and still in love with the man I married.” Her husband recently described their marriage as the process of “two people becoming one.”

See Barbara and George H.W. Bush’s Historically Long Love Story in Photos

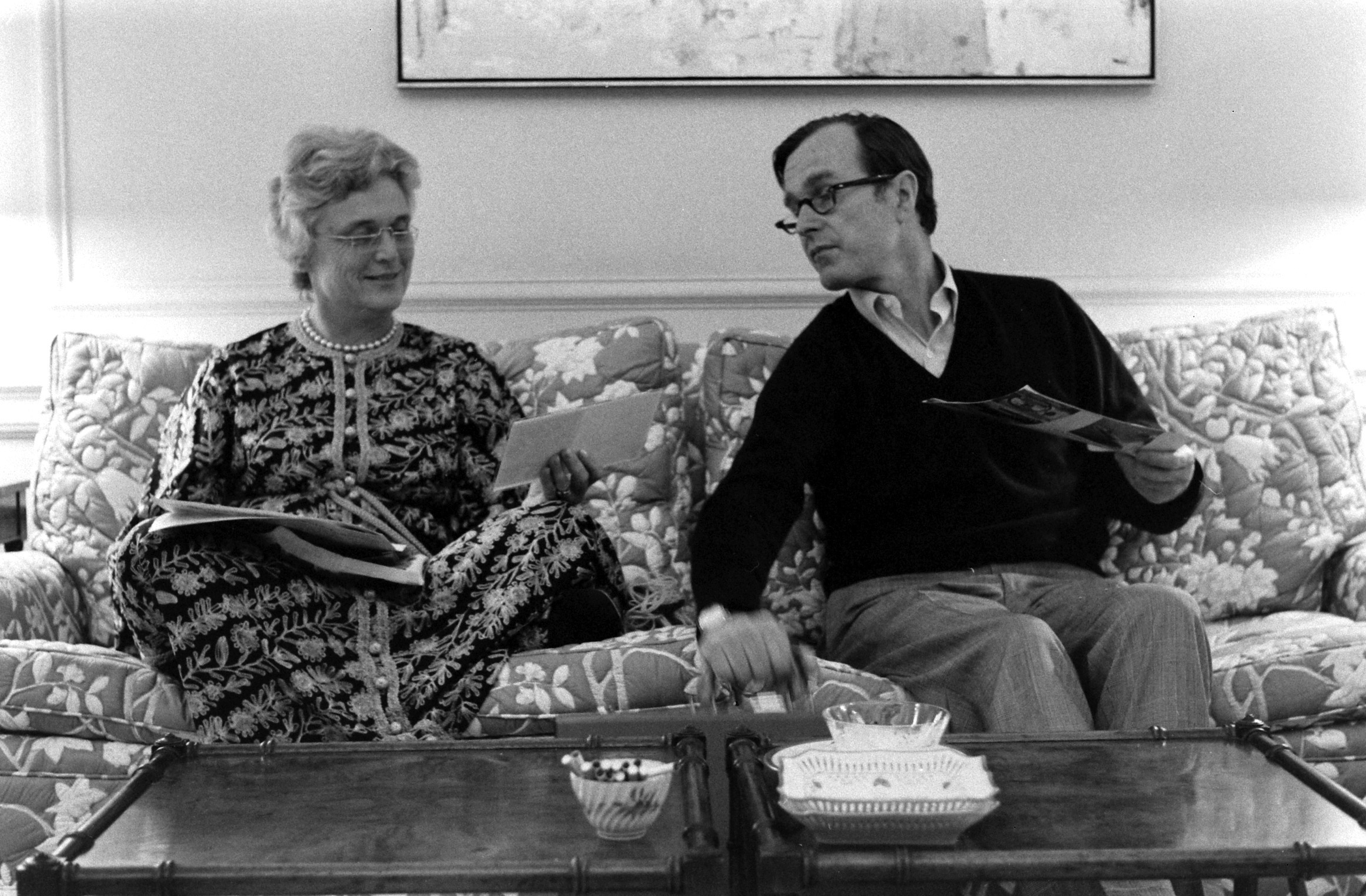

![George H. W. Bush [& Wife] Former 1st couple Barbara and George H.W. Bush enjoying life after presidency, in their living room at home in Houston, TX, 1994.](https://api.time.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/170120-barbara-george-hw-bush-14.jpg?quality=75&w=2400)

Bush was born in affluent Rye, New York on June 8, 1925, the third of four children of a father who worked his way up to become president of the McCall Corp., and a mother happy to keep house. During Christmas break her senior year at Ashley Hall, Barbara Pierce met George Bush, just out of Andover and a sketchy enough dancer, he asked her to sit out a waltz. They found two chairs and fell in love, getting secretly engaged before he shipped out to the Pacific where his plane would be shot down. They decided to wed immediately and Bush dropped out of Smith her sophomore year. “I married the first man I ever kissed,” she once said. “When I tell this to my children, they just about throw up,” she joked.

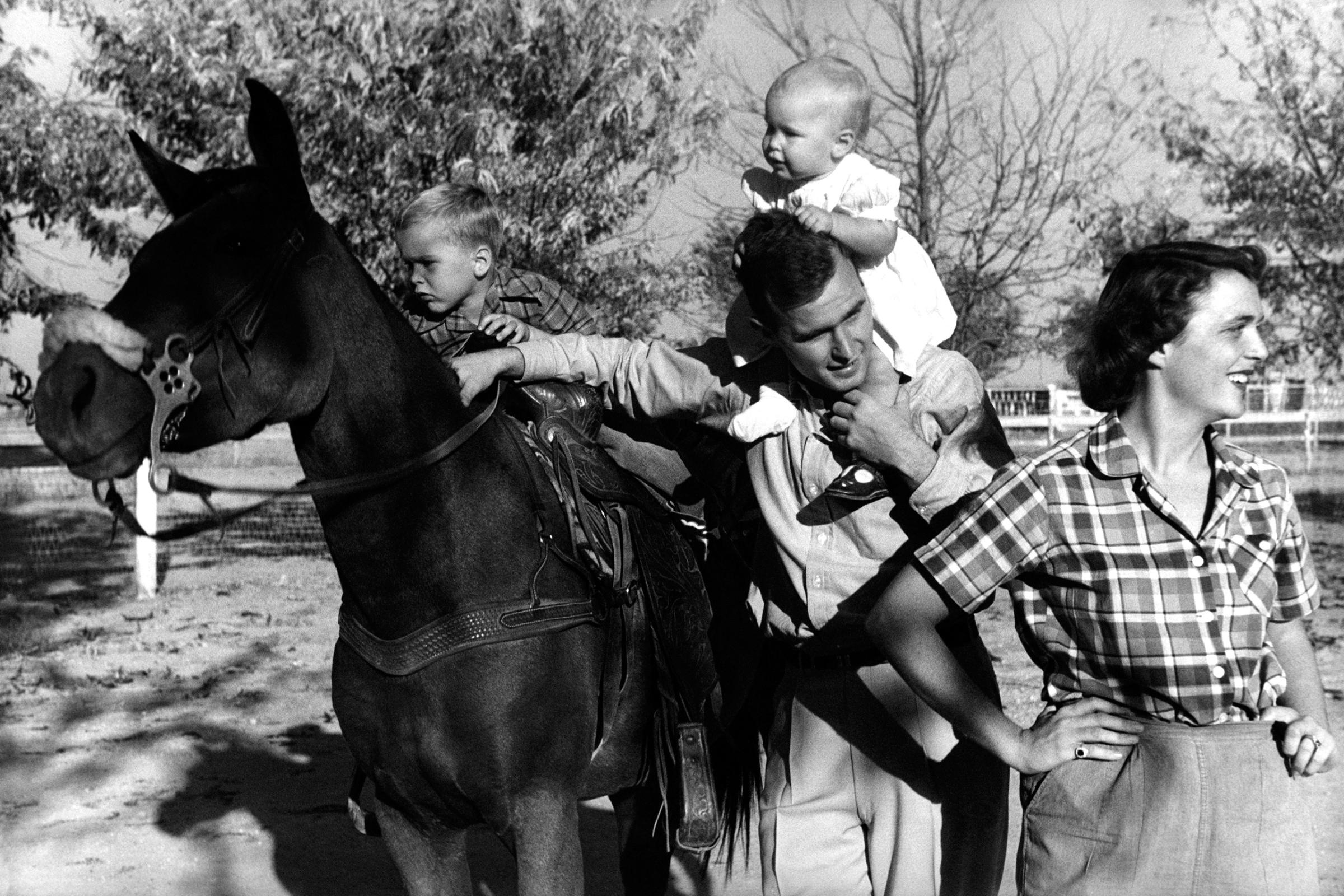

That first kiss led them west to seek their fortune in the oil fields of Texas. After Bush finished his service and graduated Yale in 1948, she packed up the Studebaker for a one-bedroom apartment in Odessa where they shared a bathroom with a mother-daughter team of prostitutes, before heading to Midland and Houston where Bush would sell his stake in Zapata Off-Shore in 1966 for $1 million.

During those years, Barbara suffered her biggest losses. In 1949 her mother died when her father lost control of the car, trying to keep a cup of coffee from spilling. In 1953, the Bushes’ second child after George, three-year-old Robin woke up feeling tired and was shockingly diagnosed with leukemia. She held on for eight months, with Barbara, whose hair turned prematurely gray, sitting by the bedside at Memorial Hospital in New York City and Bush coming on weekends. Many couples are torn apart by the loss of a child. Bush says it welded them ever more tightly together. There would be three more children, Neil, Marvin and Dorothy, “planned” she often joked to telegraph her support for Planned Parenthood.

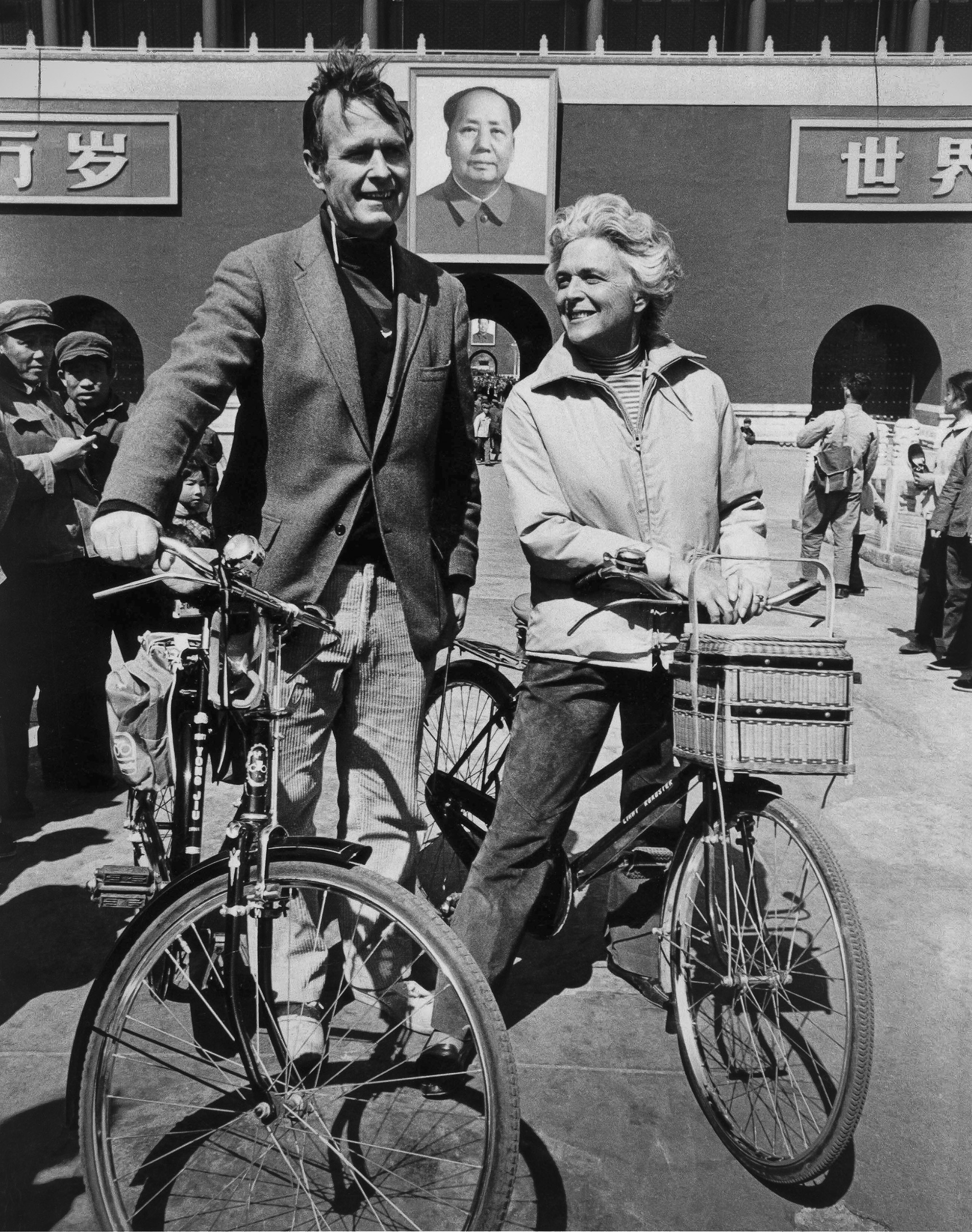

Despite being a pillar of the community, Barbara was shy. Sunk deep in diapers and dishes, scouts and Little League for so long, she lacked confidence to the point where she cried before giving a speech to the Houston Garden Club. She had a mid-life crisis where menopause, an empty nest, and incipient Graves disease left her with an undiagnosed depression that lasted months. She got over it on her own and while she never sought a career, she did become her own person. She campaigned when she could get away in Bush’s two successful races in 1967 and 1979 for a seat in Congress, and then in his losing race for the Senate. She stepped into the limelight in 1974 when Bush was appointed U.S. envoy to China. Without car pools and PTA meetings to slow her, she broke out of the small diplomatic enclave in Beijing into the Forbidden City, riding her bike everywhere, learning the language, practicing Tai Chi, and playing tennis with anyone who would join her. She wasn’t quite so happy in 1976 when President Gerald Ford made Bush director of the Central Intelligence Agency where she was no longer part of the job — for good reason, she admitted, given that she preceded many conversations with the warning, “Don’t tell George I told you this but…”

She became a co-equal partner again in 1981 when, after losing the Republican nomination for president, Bush became Ronald Reagan’s vice president, a prelude to winning the White House in 1988. Tranquility, Bush’s Secret Service name, hardly described her. Every morning began with papers, coffee, and pointed advice in bed, She tried to get Bush to give up the cowboy boots (partly successful), and embrace broccoli for the sake of children everywhere, (unsuccessful).

Her husband hates to quarrel; she didn’t mind, especially on his behalf. She promised to “retire as poet laureate” but never took back her swipe at former Democratic Vice Presidential candidate Geraldine Ferraro, whom she called a word that rhymed with “rich.” She hated the elitist rap, which is why she was so furious when reporters overplayed George’s polite inquisitiveness about a grocery scanner in his losing race for a second term as if he’d never been inside a store. In full patrician mode, she often referred to Bush’s opponent as “that woman” (Ann Richards) or “that man” (Bill Clinton) as if they weren’t in the same league as her husband.

As First Lady, as predicted, she didn’t keep getting away with murder. As offhand as she could be about being the Mom in sweat clothes, she could take offense. “Your husband is a man of the ’80s, and you’re a woman of the ’40s,” NBC Today host Jane Pauley once asked, following up, “What do you say to that?” She said nothing then but later wrote, “Why didn’t she just slap me in the face?” But mostly she turned criticism of her frumpy looks, low heels, and wearing her bathrobe to walk the dog to her advantage. Every morning in the White House, she said, she got up and started a new diet. During the Bushes’ post-election vacation, photos appeared of her swimming in a matronly bathing suit from the ’50s until she asked photographers to cap their lenses to stop her children “complaining all over the country.” Women of every political stripe were grateful that she made light of aging and the hopelessness of trying to hide it.

That didn’t mean there wouldn’t be controversy in 1990 when Wellesley College invited her to speak at its commencement. One-hundred-and-fifty students at the all women’s school signed a petition opposing her selection on the grounds that her life story did not exemplify the kind of career woman that Wellesley was graduating. She said she took their point, gave a rousing “vive la difference,” and showed up as planned, part of her pledge to be herself, but a little bit nicer.

If Bush didn’t have a career to call her own, she did have a cause she brought passion and dogged hard work to, establishing the Barbara Bush Foundation for Family Literacy in 1989. She went full bore on it after leaving the White House, giving speeches at programs around the country. People wept as she told the stories of parents, once unable to fill out school forms or follow directions, able to read Runaway Bunny to their children. Over the years she’s raised an estimated $100 million.

Read more: Inside Barbara Bush’s Quiet Yet Forceful Influence on American Politics

The annual picture taken on Walker’s Point in Kennebunkport shows a life well spent. It looks like the brochure for summer camp, albeit one run with military rules of conduct posted on every floor of the stone and shingle house earning her the nickname The Enforcer. She boasts that they all turned out pretty well, five children and their spouses, 17 grandchildren, and seven great grandchildren bunking all over as they came every June to celebrate her birthday. She’s catalogued their history in more than 60 carefully documented scrapbooks. She could have run a cabinet department, or two.

Instead, she ran a family. Her last contribution came as she lay dying. Most public figures prefer to be seen as “battling” a disease, and “fighting” to the death, not willing to shine a light on the more passive palliative care. But among the many paying jobs Bush didn’t have was as a volunteer in the 1960s at the Washington Home for the critically ill. As a congressional spouse, she helped found a hospice center there, a model of its time for those who wanted to opt out of the end-of-life heroic, but futile, medical treatment in favor of “comfort care.” Last weekend, she left the hospital for home where she died without the clamor of machines or the presence of strangers. By her example, she let the rest of us know it’s all right to go gently into the dark night.

No First Lady escapes microscopic scrutiny. She bears all of America’s conflicting notions about women as wives, mothers, lovers, colleagues, and co-presidents. Bush’s informality, no-nonsense style, her perceived noblesse oblige offended some. To many more, she was a welcome antidote to appearances over substance and to the flash and the greed of the ’80s. Barbara Bush’s unspoken message may be as important as anything she did: the proposition that there is honor in “just being” a wife and mother. It’s O.K. to be a plus size. A lined face is the price of living. There’s great joy to be found in serving others.

Bush summed up her life as the luckiest imaginable, one where she never got over meeting and marrying the dashing, lanky Yale first baseman, a scion of the Walker and Bush clans, who was taken by the chubby girl whose mother wouldn’t serve her dessert in hopes she would slim down. She didn’t need him to give her class — she had a President Pierce in her lineage — but he did need her to tease him and make him laugh, point out the phonies, and have his back. It’s facile to say he wouldn’t have been president without her, but it’s a fact that of all the Ivy League graduates who become Congressmen and see a president in the mirror looking back, he was one of the few to make it.

The former president once wrote to his wife, “You have given me joy that few men know… I have climbed perhaps the highest mountain in the world, but even that cannot hold a candle to being Barbara’s husband.” As she told those Wellesley students, the ones who wanted her to come and those who didn’t, “At the end of your life, you will never regret not having passed one more test, not winning one more verdict or not closing one more deal. You will regret time not spent with a husband, a child, a friend or a parent.”

From the rest of us, to the girl who sat out the dance, fell in love at 17, gave up a college degree to get married and embark on a journey not of her own making but one that would have been impossible without her, we thank you for your service.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Caitlin Clark Is TIME's 2024 Athlete of the Year

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com