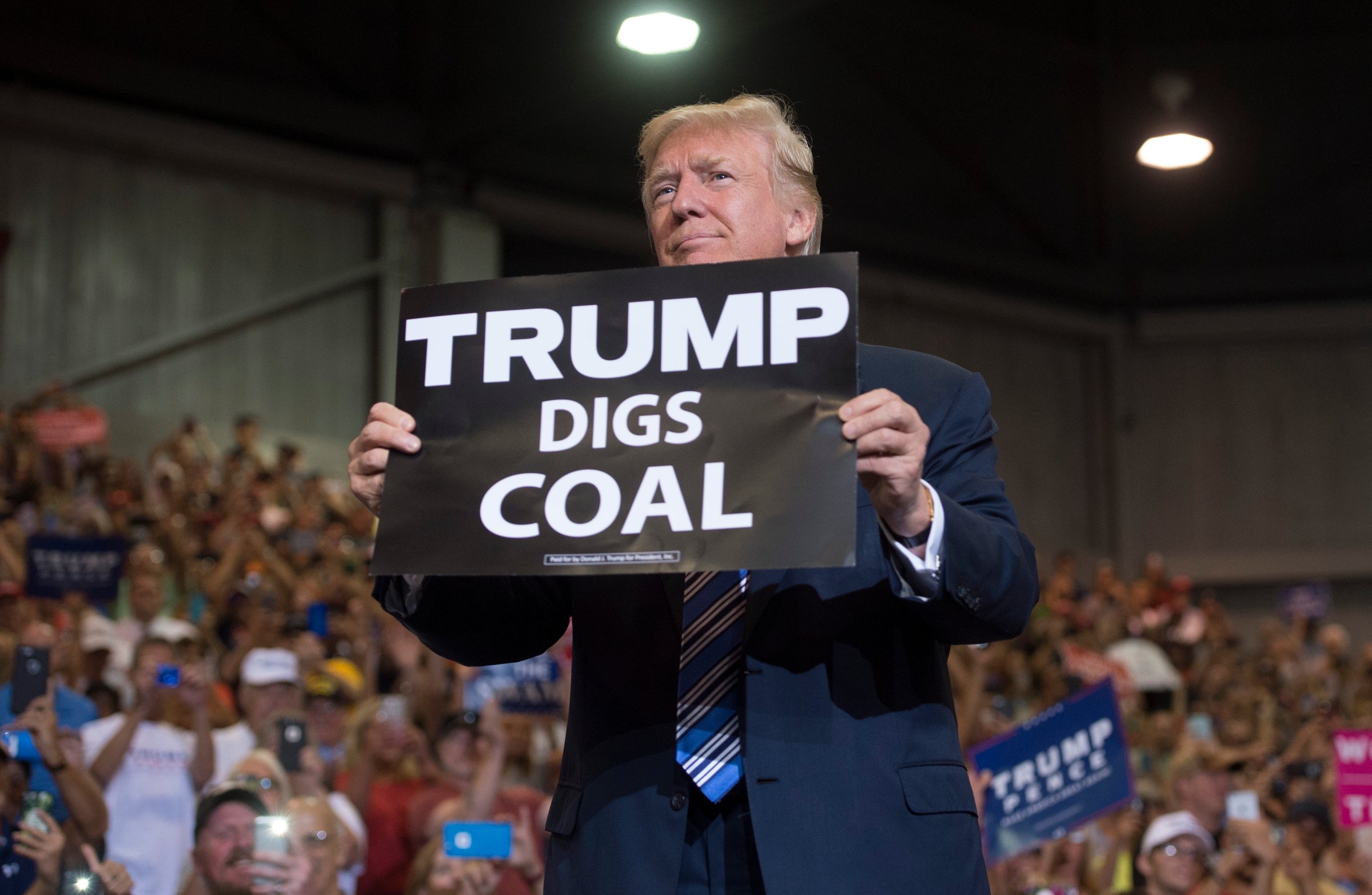

The Trump Administration has taken a number of steps to help the ailing U.S. coal industry, but some think its biggest savior may turn out to be foreign countries in need of energy.

As natural gas, wind and solar power have become more competitive on cost, foreign markets have helped halt the precipitous drop in coal production, at least temporarily, and contributed to forecasts for future production that level off rather than declining.

Most importantly, China largely dictates the global coal market because it uses so much of the fossil fuel, about half of the global total, and the country’s use of coal increased slightly in 2017 after falling in the previous three years. The country also cut production in a type of coal used to produce steel, causing prices of that type of coal to triple. With higher coal demand, the U.S. exported coal around the world, with India, the Netherlands and South Korea ranking as the largest recipients of U.S. coal.

“There’s a need for our coal around the world and they want to burn our coal around the world,” Bob Murray, CEO of Murray Energy, one of the largest domestic coal producers, told TIME last week. “It’s been an offset to a great extent to the loss of domestic coal.”

U.S. coal exports increased more than 60% between 2016 and 2017, according to data from the Energy Information Administration. The spike in exports corresponds to an increase in global prices driven largely by strong demand from China and unanticipated disruptions in other coal-producing countries, such as a cyclone in Australia that disrupted the country’s energy infrastructure.

But analysts say the export boon will not last forever. The temporary disruptions to the market have lifted and China’s demand for coal for power production is expected to level off in the coming years as economic growth slows and the country continues its push to develop renewable energy sources such as wind and solar as a means to reduce air pollution and fight climate change.

Overall, U.S. coal exports are expected to fall slightly in 2018 and 2019, a significant if not game-changing switch in direction. In the longer term, flatlining is the best-case scenario for the industry and further advances in other energy sources could lead to an accelerated decline in the coming decades, according to a 2017 EIA projection.

More significantly for the 50,000 people who still work in the coal mining industry, even a flatlining would likely mean continued job losses as industry managers learn to work more efficiently. Automation and mechanization will also reduce the labor demand, says Trevor Houser, who leads the research company Rhodium Group’s energy and climate team.

“If history is any guide, flat domestic coal consumption is going to mean continued declines in U.S. coal employment,” he says.

The long-term trajectory helps explain why the Trump Administration has been so eager to step in to support the coal industry. The administration has launched a broad-based effort to repeal environmental regulations, including the Environmental Protection Agency’s Clean Power Plan, which pushed states away from operating coal-fired power plants.

More aggressively, Trump’s Department of Energy proposed an emergency plan last year that would have subsidized coal-fired power plants on the grounds that closing them would hurt the resilience of the electric grid. The agency argued that the coal-fired and nuclear power plants are the most reliable source of energy in the event of a disruption like a natural disaster because the fuel source is stored on site. Federal regulators unanimously rejected that plan, but DOE has insisted that it will find a way to stem the industry’s losses.

“We have to spend some money to guarantee the freedom and security of this country,” Energy Secretary Rick Perry said at the Bloomberg New Energy Finance conference in New York last week.

How exactly it plans to do that remains unclear. The agency is currently considering whether to bail out nuclear and coal-fired power plants owned by the Ohio-based company FirstEnergy Solutions, which filed for bankruptcy earlier this month. The reasoning for such a bailout would be similar to the Department of Energy proposal but narrowly tailored to help this specific company.

Ultimately, Trump may be close to exhausting potential avenues to aid the coal industry, whose greatest foe is competition from other fuel sources and not government policy. But that does not mean that coal executives who ardently backed his candidacy will stop asking for help.

In a wideranging interview on the sidelines of a renewable energy conference, Murray claimed, falsely, that there is no scientific consensus on climate change, charged that the controversy surrounding EPA head Scott Pruitt was concocted by liberals to deter the “star” of the Trump administration and insisted that his business was not endanger of going bankrupt.

But Murray, whose company donated at least $1 million to a Trump supporting Super Pac last year alone, reserved his most impassioned remarks when talking about the health of his industry.

“They get it,” Murray said of the Trump Administration. “The options are becoming fewer. That’s correct. But it has to be dealt with.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Breaking Down the 2024 Election Calendar

- How Nayib Bukele’s ‘Iron Fist’ Has Transformed El Salvador

- What if Ultra-Processed Foods Aren’t as Bad as You Think?

- How Ukraine Beat Russia in the Battle of the Black Sea

- Long COVID Looks Different in Kids

- How Project 2025 Would Jeopardize Americans’ Health

- What a $129 Frying Pan Says About America’s Eating Habits

- The 32 Most Anticipated Books of Fall 2024

Write to Justin Worland at justin.worland@time.com