The second time I got sober, I started praying with a sense of purpose. It was impossible to picture the clear outline of any god, but praying regularly was a way to separate my second sobriety from my first one. Back then I’d only prayed haphazardly — when I wanted something, basically. This time around, I understood arranging my body into a certain position twice a day as a way to articulate commitment rather than a bodily lie, a false pretense. I prayed in the bathroom — by the toilet, under the dirty skylight over our shower — where my boyfriend, Dave, wouldn’t see me. He wasn’t judgmental; I was just embarrassed. It was easier to be alone with my fumbling faith, and it felt good to kneel on the bathroom floor for different reasons than I’d knelt on them before: not throwing up or getting ready to throw up, but closing my eyes and asking to be useful. I’d been told to pray for people I resented, so I prayed for Dave and for every girl he’d ever flirted with, for every man I’d ever hated for not wanting me. I even liked the physical residue of these morning prayers, the tangled red pattern on my knees from the bath mat we didn’t clean enough.

When I was younger, I’d gone — reluctantly — to a regal Episcopal church in Inglewood. My mother had started going to church after she and my father divorced, and she’d asked me to come with her. The church was stunning, with massive copper lanterns hanging from the wooden beams, and jeweled light stilled by the stained glass windows on Sunday mornings: angels with red-tipped fiery wings. The golden altar held a pale statue of Jesus with a sculpted triangular beard and ruthlessly serene eyes, his finger raised as if he were just about to say something. But what? Going to church meant sensing something just out of reach — a sense of connection to this pale man, or the sermon, or the songs — the ecstatic faith that seemed to swell inside everyone else. I wasn’t sure I believed in God, so wouldn’t it be lying if I prayed to him? The premise of the miracle at the heart of everything, that impossible resurrection, made me feel miserly with disbelief, like my heart was a locked storefront shuttered against sublimity. I was shy and uncomfortable in my own body, kneecaps bruised by wooden kneelers, afraid of the vulnerabilities of belief — afraid to find anything too beautiful, or fall for it.

Because I wasn’t baptized, I couldn’t take communion, so I either sat alone in my pew while everyone else walked up to the altar, or else I went forward and knelt on the velvet cushion, arms crossed over my chest, while the priest placed his palm on my head and said: “I bless you in the name of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit.” But I didn’t believe in any of them, and it seemed dishonest to take a blessing in their name. The more you had to make yourself believe, I was sure, the more false your belief was.

Years later, recovery turned this notion upside-down — it made me start to believe that I could do things until I believed in them, that intentionality was just as authentic as unwilled desire. Action could coax belief rather than testifying to it. “I used to think you had to believe to pray,” David Foster Wallace once heard at a meeting. “Now I know I had it ass-backwards.” For a long time, I’d believed that sincerity was all about actions lining up with belief: knowing myself and acting accordingly. But when it came to drinking, I’d parsed my motivations in a thousand sincere conversations — with friends, with therapists, with my mother, with my boyfriends — and all my self-understanding hadn’t granted me any release from compulsion.

This ruptured syllogism — If I understand myself, I’ll get better — made me question the way I’d come to worship self-awareness itself, a brand of secular humanism: Know thyself, and act accordingly. What if you reversed this? Act, and know thyself differently. Showing up for a meeting, for a ritual, for a conversation — this was an act that could be true no matter what you felt as you were doing it. Doing something without knowing if you believed it — that was proof of sincerity, rather than its absence.

I didn’t know what I believed, and prayed anyway. I called my sponsor even when I didn’t want to, showed up to meetings even when I didn’t want to. I sat in the circle and held hands with everyone, opened myself to clichés I felt ashamed to be described by, got down on my knees to pray even though I wasn’t sure what I was praying to, only what I was praying for: don’t drink, don’t drink, don’t drink. The desire to believe that there was something out there, something that wasn’t me, that could make not-drinking seem like anything other than punishment — this desire was strong enough to dissolve the rigid border I’d drawn between faith and its absence. When I looked back on my early days in church, I started to realize how silly it had been to think that I’d had a monopoly on doubt, or that wanting faith was so categorically different from having it.

When people in the program talked about a Higher Power, they sometimes simply said “H.P.,” which seemed expansive and open, a pair of letters you could fill with whatever you needed: the sky, other people in meetings, an old woman who wore loose flowing skirts like my grandmother had worn. Whatever it was, I needed to believe in something stronger than my willpower. This willpower was a fine-tuned machine, fierce and humming, and it had done plenty of things — gotten me straight A’s, gotten my papers written, gotten me through cross-country training runs — but when I’d applied it to drinking, the only thing I felt was that I was turning my life into a small, joyless clenched fist. The Higher Power that turned sobriety into more than deprivation was simply not me. That was all I knew. It was a force animating the world in all of its particular glories: jellyfish, the clean turn of line breaks, pineapple upside-down-cake, my friend Rachel’s laughter. Perhaps I’d been looking for it — for whatever it was — for years, bent over the toilet on all those other nights, retching and heaving.

When Charles Jackson reread The Lost Weekend, years into his inconstant sobriety, he “was most of all impressed by the sense that, in spite of the hero’s utter self-absorption, it is a picture of a man groping for God, or at least trying to find out who he is.” He understood the old patterns as driven by the same hungers: the hunger for booze as the hunger for God, all this groping as part of the same journey.

At times, it seemed my relationship wasn’t to a Higher Power but to the act of prayer itself — a ritualized cry of longing and insufficiency — as if my faith were a catalogue of places I’d gotten on my knees, a hundred bathrooms where I’d knelt on cold tiles with thin ribbons of grout under my shins; or crouched on a foot-worn bathmat, facing the eye-level skyline of my mother’s bubble bath, jars of pearly peach and vanilla. In those bathrooms, God wasn’t faceless omnipotence but proximate particulars, grout and soap — the things that had always been there, right in front of me.

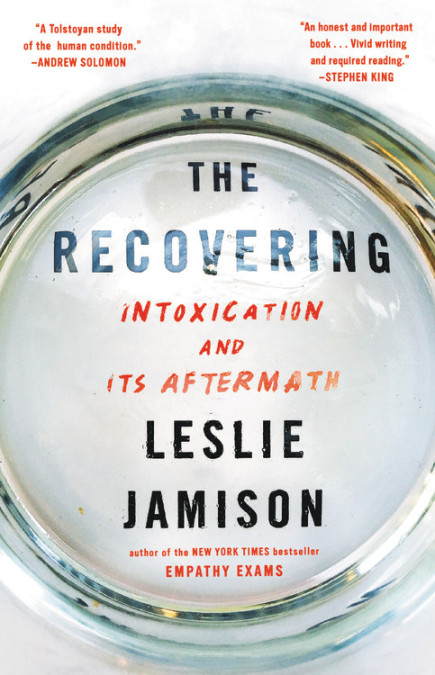

Excerpted from The Recovering: Intoxication and Its Aftermath. Copyright © 2018 by Leslie Jamison. Reprinted with permission of Little, Brown and Company. All rights reserved.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com