When Jeff Sessions was a boy of 7 or 8, he had a dog that followed him everywhere. But one day, the dog got him in trouble. Sessions had run with the mutt into the woods of rural Alabama, figuring it knew where it was going. By the time he realized he was wrong, the two of them were hopelessly lost. “They closed all the stores and everyone had to go looking for me,” Sessions recalled with a chuckle. “My excuse was, I was just following him.”

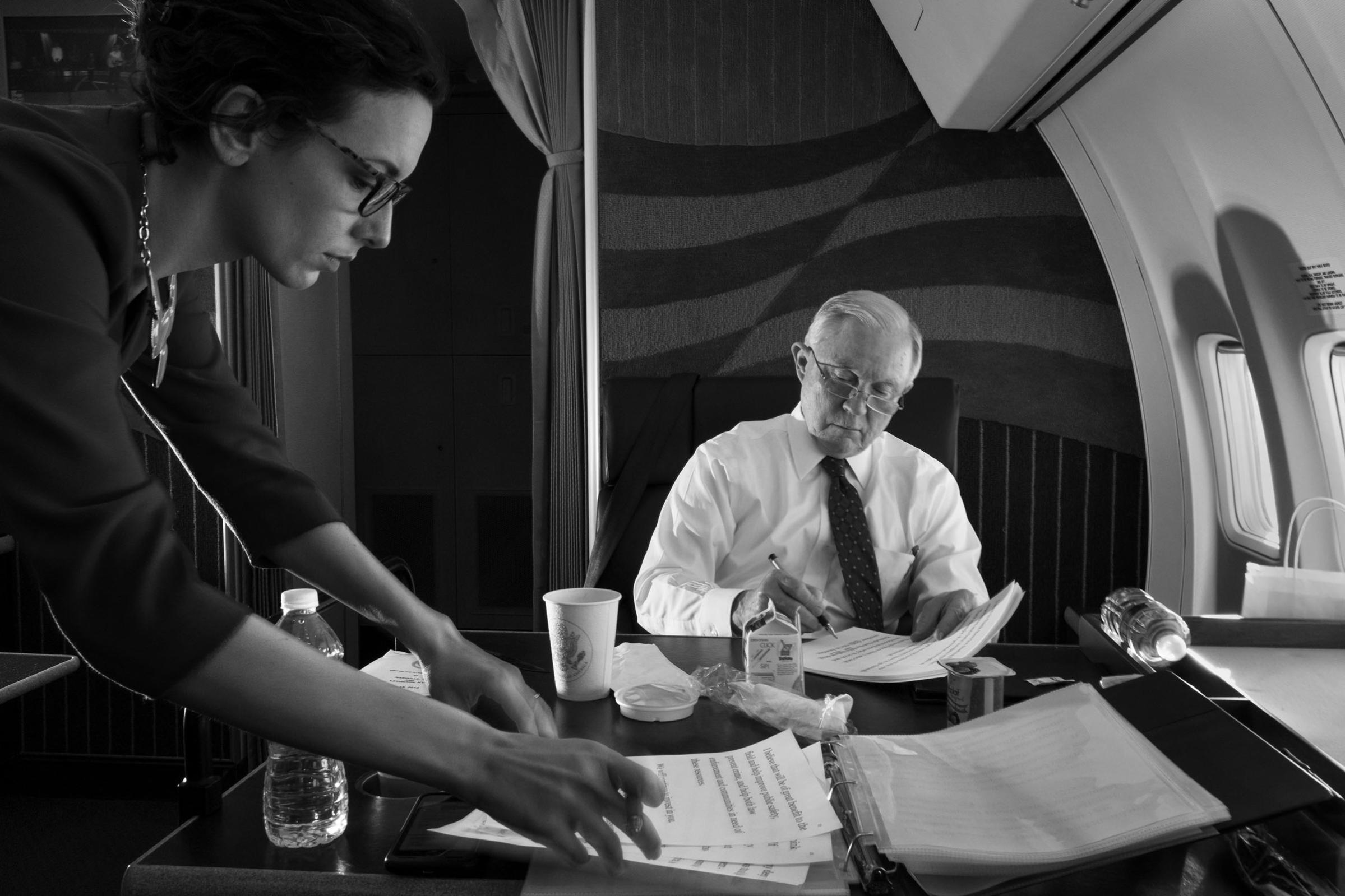

Sessions told me this story on March 15–the day before he fired former deputy FBI director Andrew McCabe–from his blue vinyl club chair on the military jet that had whisked the U.S. Attorney General away from Washington. It had the ring of a parable: beware those who seem the most loyal to you; it is they who will lead you astray.

Donald Trump once followed Sessions’ lead, promising as a candidate the crackdowns on crime, immigration and trade for which Sessions crusaded in the Senate. The first Senator to endorse Trump, Sessions gave him credibility with the far right and provided the intellectual framework for his law-and-order sloganeering. And as Attorney General, he has turned Trump’s rhetoric into reality, emerging as the most effective enforcer of the President’s agenda.

But if the fixation on law and order brought Sessions and Trump together, it is also what has rent them asunder. When Sessions recused himself a year ago from the investigation into Russian meddling in the 2016 U.S. presidential election, he set in motion the chain of events that culminated in the appointment of special counsel Robert Mueller. Trump has never forgiven him. In public and private, the President has denigrated the proud former Senator, calling him an “idiot,” “beleaguered” and “disgraceful.”

The broken relationship has turned the job of a lifetime into an exercise in humiliation. Rumors that Sessions’ neck is on the chopping block are constant, and Environmental Protection Agency chief Scott Pruitt has been angling to replace him. As Sessions and I spoke on the plane, he was headed to Nashville to give a speech to a police chiefs’ convention, followed by a stop in Lexington, Ky., to meet with prosecutors, police and families affected by the opioid crisis. All the while, Fox News played on mute above his head, its chyrons questioning whether Sessions was about to be fired.

Even if his tenure ends tomorrow, Sessions would leave a legacy that will affect millions of Americans. He has dramatically shifted the orientation of the Justice Department, pulling back from police oversight and civil rights enforcement and pushing a hard-line approach to drugs, gangs and immigration violations. He has cast aside his predecessors’ attempts to rectify inequities in the criminal-justice system in favor of a maximalist approach to prosecuting and jailing criminals. He has rescinded the Obama Administration’s Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program and reversed its stances on voting rights and transgender rights. “I am thrilled to be able to advance an agenda that I believe in,” he told a group of federal prosecutors in Lexington later that day. “I believed in it before I came here, and I’ll believe in it when I’m gone.”

Sessions’ liberal critics agree that he’s been remarkably effective. That’s why they find him so frightening. He has, they charge, put the full force of law behind Trump’s racially coded rhetoric. “The Justice Department is supposed to be protecting people, keeping people safe and affirming our basic rights,” says Senator Cory Booker of New Jersey, a Democrat who took the extraordinary step of testifying against a fellow Senator during Sessions’ confirmation hearings last year. “But he has rolled back the Justice Department’s efforts to do that.” The irony of Sessions’ position is that the same critics who despise his policy initiatives are adamant that Trump should not remove him. “Jeff Sessions is not acting in defense of the rights of Americans. He should not be in that job,” Booker told me. “But I do not think he should be fired for the reasons Donald Trump would fire him.”

As the chaos in the White House rages and threatens to consume him, Sessions professes to pay it no heed. “I want to do what the President wants me to do,” he said in his slow, drawling voice, his blue-green eyes peering over the top of his glasses. A wry smirk lifted a corner of his lips. “But I do feel like we’re advancing the agenda that he believes in. And what’s good for me is it’s what I believe in too.”

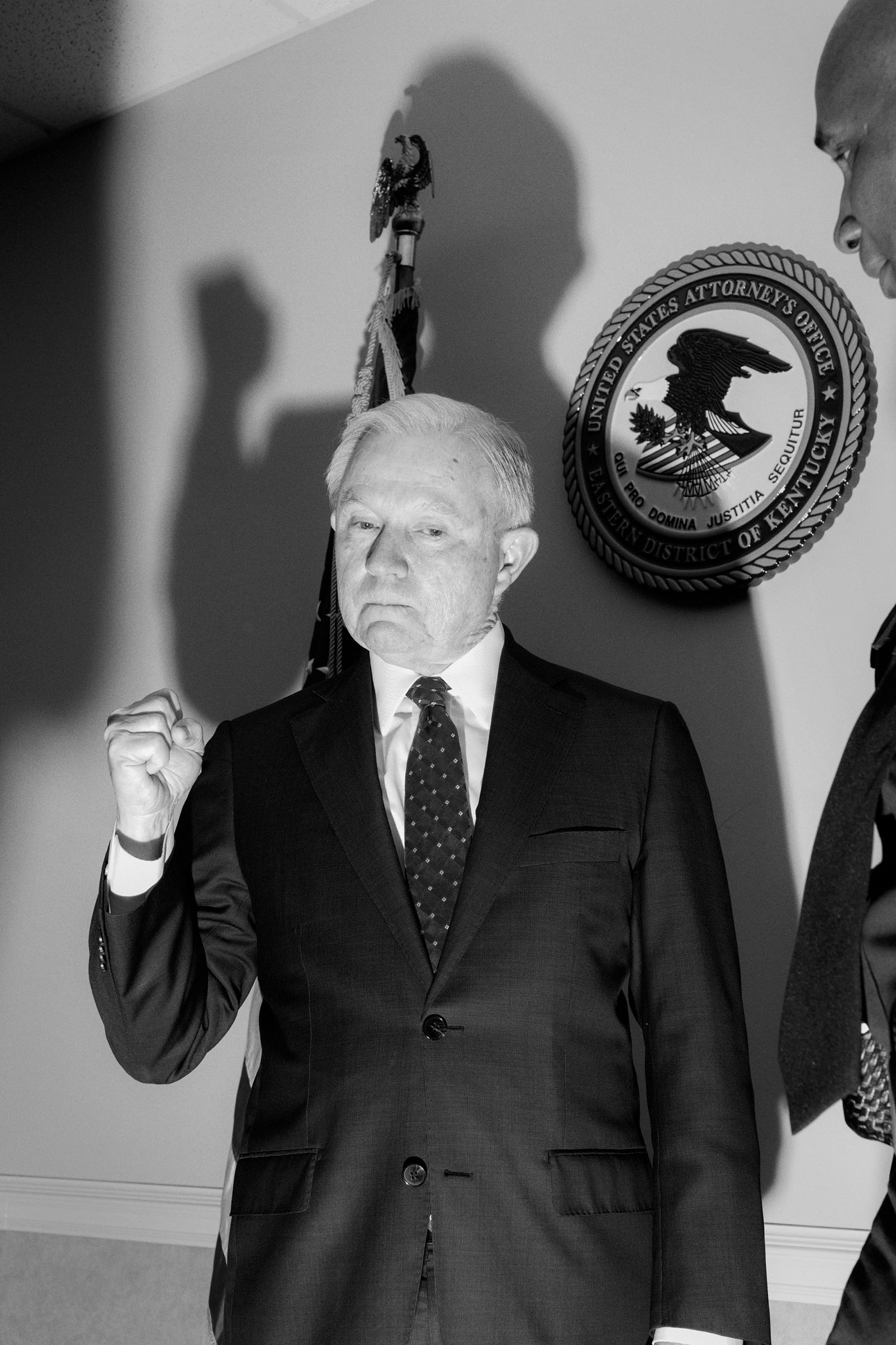

It was a brisk, sunny day in Lexington, with dirty clumps of snow still clinging to the ground. Sessions marched across the tarmac into the waiting motorcade. At 71, he is full of energy, and his slight stature and elfin ears give him a buoyancy that belies his severe views. His bright eyes and upturned mouth make him look like he’s smiling even when he’s delivering a jeremiad against criminals or foreigners.

In an upstairs room in the building housing the U.S. Attorney’s office, a group of white people sat in a semicircle, surrounded by framed photographs of their dead loved ones. Sessions sat before them, listening to their pleas for more help from the federal government. “‘Just say no,’ it won’t work with this drug,” said a stocky man named Dennis, whose 24-year-old daughter died of a fentanyl overdose.

After hearing the stories, Sessions had a question. “How many of your children had treatment before they died?” Seeing nearly all the hands raised, he nodded grimly. “Well, we need treatment,” he said, “but it is true that a lot of people it doesn’t work for.”

What does work, according to Sessions, is arresting people and locking them up. He has stuck to this stance, forged by his work as a prosecutor in the 1970s and ’80s, even as the mainstream consensus has shifted. In recent years, most experts have come to view the war on drugs as a counterproductive failure, and a bipartisan movement for criminal-justice reform seeks to soften the harsh and unequal penalties it imposed.

The reformers have made considerable headway at the state level. Texas has closed eight prisons and saved millions of dollars without seeing crime rise. In the ’80s and ’90s, “we put a lot of people in prison, but there’s no evidence that made us any safer,” says Koch Industries’ Mark Holden, who has led the conservative Koch brothers’ push on the issue. (Koch Industries, through a subsidiary, is an investor in Meredith Corporation, TIME’s parent company.)

Under Obama, the Justice Department investigated local police departments, exposing systematic mistreatment of minorities, and secured agreements, known as “consent decrees,” to reform their practices. Attorney General Eric Holder launched a “smart on crime” initiative urging federal prosecutors to use discretion in seeking harsh sentences. Reform efforts have helped reduce the federal prison population from 220,000 to 180,000 in the past five years. To Obama’s progressive supporters, these changes were among his greatest strokes of racial progress.

But in the view of Sessions and his supporters, including many in law enforcement, the reformers have it backward. Under Obama, Sessions believes, the DOJ sent all the wrong signals, demoralizing police officers and soft-pedaling the dangers of drugs. In speeches, he cites the shrinking prison population not as a breakthrough but as a worrisome trend. “We’ve got some space to put some people!” he told the chiefs in Nashville. Sessions believes today’s low crime rates are a direct result of “proactive policing” and harsh sentences, and that dialing them back is causing crime to rise. According to the FBI, the violent crime rate rose 7% between 2014 and 2016, and the murder rate rose 20%, following years of decline.

Sessions has moved swiftly to unwind the Obama Justice Department’s policies. He canceled the “smart on crime” initiative and replaced it with a directive to pursue maximal charging and sentencing. He pulled out of the consent decrees and rescinded Holder’s hands-off marijuana-enforcement policy. He announced the end of DACA, stepped up deportation orders and sued California over sanctuary cities. He has embraced Trump’s call to impose the death penalty on some drug dealers, which some legal scholars consider unconstitutional. Emphasizing treatment for drug addicts isn’t just ineffective, according to Sessions–it’s dangerous. “The extraordinary surge in addiction and drug death is a product of a popular misunderstanding of the dangers of drugs,” he told me. “Because all too often, all we get in the media is how anybody who’s against drugs is goofy, and we just ought to chill out.”

In February, Sessions sent a letter warning the Senate that a bill to reduce federal sentences risked “putting the very worst criminals back into our communities.” (An outraged Chuck Grassley, the Republican Senator from Iowa, told reporters that if Sessions wanted to keep making laws, he should go back to elected office.) Sessions believes his erstwhile colleagues have been misled. “This whole mentality that there’s another solution other than incarceration,” he told me, “all I will say to you is, people today don’t know that every one of these things has been tried over the last 40 years.”

Sessions seemed exasperated when I asked him to address the disproportionate impact of harsh policing and incarceration on black families and communities. He cited the work of Heather Mac Donald, the controversial conservative scholar who argues that racial bias in the criminal-justice system is a myth and that the real problem is a “war on cops.” Mac Donald popularized the concept of the “Ferguson effect,” an unproven theory that crime rises when police feel hamstrung by political oversight. Sessions embraces this notion. In cities like Baltimore and Chicago, he told me, politicians “spend all that time attacking the police department instead of the criminals.”

To critics, all these theories are no more than window dressing for a racist system that intimidates, imprisons and kills black people indiscriminately in order to make white people feel safe. Since the 1960s, “law and order” has been a coded political slogan, a fear-based appeal to galvanize white voters. “There is a consensus that the war on drugs of the 1980s and ’90s destroyed communities, disproportionately impacted people of color, ballooned the criminal-justice system and the prisons, and exacerbated poverty and inequality in our country,” says Todd Cox, director of policy for the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund. By turning the Justice Department away from civil rights and toward harsh enforcement, Sessions embodies what many see as the institutional racism of the Trump Administration. He has taken the racially coded messages that served as dog whistles during the campaign and operationalized them into policy.

The conviction among his critics that Sessions is racist has sometimes led them to overreach. In February, a Democratic Senator and the American Civil Liberties Union blasted him for referring to the “Anglo-American heritage of law enforcement” in a speech. It was a factual description, one Obama had used on many occasions. But in explaining it to me, Sessions couldn’t resist a detour into cultural stereotypes. “I believe the American legal system, which clearly developed out of England, is a wonder of the world, and it’s based on the fact that lady justice is blindfolded,” he said. “When you go and travel like I have–to Kosovo, to Afghanistan, to Iraq–where we’ve invested huge amounts of money and effort to export our legal system to a culture that’s totally unfamiliar with it, it doesn’t work. It’s because it requires a degree of trust and respect, education and maybe even a cultural predisposition.”

Sessions contends that the policies he champions help minority communities by cleaning up their neighborhoods. “If you do the map of your city and you’ve got five times the murders in a minority neighborhood, do you just go away?” he asked me, eyes narrowed. “Or do you prosecute the criminals who are committing the murders? That’s the fundamental answer. And the other thing is, you think the mothers who’ve got children, the older people who are afraid to walk to the grocery store–shouldn’t they be free just like they are in the elite part of town?”

Sessions leaned over the plastic airplane table. “Whose side are you on?” he asked. “I’m on the victims’ side, and overwhelmingly the victims are minorities. The prosecution of certain minorities for murder, the victim is overwhelmingly another African American or Hispanic. It occurs within their own communities.” (Law-enforcement statistics show white criminals also tend to target white victims.)

His eyes gleamed as he sat back. “We are protecting minority citizens,” he concluded. “The fundamental question is, Who rules the streets? The government, or the outlaws?”

Jefferson Beauregard Sessions III grew up in Hybart, a small town in rural southwestern Alabama, where his father owned a country store. He was raised to follow the rules. “I was always persnickety about integrity and all that,” he said. The troubled history of race in America runs through his family. His grandfather, the original J.B. Sessions, was named after two icons of the Confederacy, Jefferson Davis and P.G.T. Beauregard, and was 2 when his own father died at Antietam. Sessions’ ancestors migrated south in the 1830s, when President Andrew Jackson forcibly removed Native Americans from the land that is now Alabama to accommodate the growing white population. Like many white Southerners of long lineage, he is descended from numerous slave owners, including his mother’s great-grandfather Oliver Powe, who the 1860 Census records as having owned 25 slaves.

Sessions attended segregated schools and an all-white university. After earning his law degree from the University of Alabama, he joined the U.S. Attorney’s office in Mobile, and in 1986, then President Reagan nominated him for a federal judgeship. Sessions’ confirmation turned contentious when the Senate Judiciary Committee confronted him with charges of racism. A black assistant U.S. Attorney testified that Sessions had addressed him as “boy” and had said that he thought the Ku Klux Klan was all right until he found out they smoked pot. (Sessions said he was joking.) Just as disturbing to liberals on the committee was a voter-fraud case Sessions had brought against a group of civil rights activists who were helping black voters cast their ballots. (The activists were acquitted.) Sessions protested that he was not a racist, and had allowed civil rights cases to move through his office. His nomination was rejected with a combination of Democratic and Republican votes.

Elected to the Senate in 1996, Sessions became known as a dogmatic outlier. As many Republicans called for increases in legal immigration and clemency for the undocumented, Sessions gave fiery floor speeches denouncing those ideas. He also jibed with Trump on trade, having come to view big global agreements as a raw deal for the American worker. With less immigration and fewer imported goods, he reasoned, companies would be forced to produce their wares in America, using American workers paid a substantial wage. Most economists disagree, arguing that even if these policies were feasible, they would raise prices and lower living standards.

Another crucial element of Sessions’ worldview was his sense of resentment against elites. He saw what he called “Wall Street geniuses” and “masters of the universe” as out of touch with his working-class constituents’ lives. “He was extraordinarily consistent,” says Josh Holmes, a former chief of staff to Senate majority leader Mitch McConnell, and “sort of the opposite of a chamber of commerce Republican.”

Although his crusades were often lonely, Sessions could be effective. In 2013, when a bill providing a pathway to citizenship for undocumented immigrants had support from powerful advocates across the political spectrum, Sessions was its loudest critic. He couldn’t keep it from passing the Senate but successfully led the charge to stop it in the House. The conservative National Review dubbed him “Amnesty’s worst enemy.”

If many of Sessions’ colleagues regarded him as a gadfly, a growing faction of the hard right came to see him as a hero. The nationalist views he espoused attracted the attention of Breitbart.com and its then chairman, Stephen Bannon. At a time when many Republicans thought only a message of moderation could win back the White House, Bannon, who would go on to become Trump’s chief campaign and White House strategist, was inspired by Sessions’ insistence that restricting immigration and trade could be a political winner. As Sessions wrote in a 2012 memo to his colleagues: “This humble and honest populism–in contrast to the [Obama] Administration’s cheap demagoguery–would open the ears of millions who have turned away from our party.”

In 2013, Bannon tried to convince Sessions to run for President; he demurred. But Sessions was pleasantly surprised when Trump began campaigning on his old themes. Sessions’ aide Stephen Miller went to work for Trump’s campaign, helping shape his policy platform on immigration, trade and other issues. Just before Super Tuesday, Sessions became the first and only Senator to endorse Trump in the primary, dealing a blow to then rival Ted Cruz. Accepting the endorsement at a massive rally in Madison, Trump called Sessions “a great man.”

Sessions became a close and trusted adviser to the campaign. He was thrilled that Trump had become the pitchman for his positions. “Here he comes on all of it, boom boom boom,” Sessions told me. “Nobody else was saying that.”

As the sun set outside the plane window, Sessions began to wax philosophical about the rule of law. The Attorney General’s job, he said, is to tell the executive what he can and can’t do legally. Tenting his fingers beneath his chin, Sessions said he stands by his recusal from the Russia investigation: “I think I did the right thing. I don’t think the Attorney General can ask everybody else in the department to follow the rules if the Attorney General doesn’t follow them.”

Trump appears to see it differently; he has reportedly griped that Sessions has failed to “protect” him. “He does get frustrated,” Sessions concedes. “He’s trying to run this country, and he’s got to spend his time dealing with certain issues.”

Like so many Republicans, Sessions has accommodated himself to Trump in ways that seem to contravene his principles. The day after I interviewed him, Sessions–acting on a recommendation from the inspector general and FBI disciplinary officials–fired the FBI’s McCabe two days before he was set to retire. McCabe decried the act as politically motivated retaliation, an impression Trump bolstered with a set of gloating morning-after tweets. It was subsequently reported that McCabe had previously investigated Sessions over his Russian contacts.

Still, when it comes to the Russia investigation, Sessions has held the line against Trump’s interference. Shortly before our trip, he had dinner at a Washington restaurant with Solicitor General Noel Francisco and Deputy Attorney General Rod Rosenstein, the official overseeing the Mueller probe. The tiniest of symbolic protests, it nonetheless reportedly sent Trump into a rage. Sessions declined to comment on the dinner conversation, but he did say he ordered the fried chicken–a house specialty–and a banana split that was too big to finish.

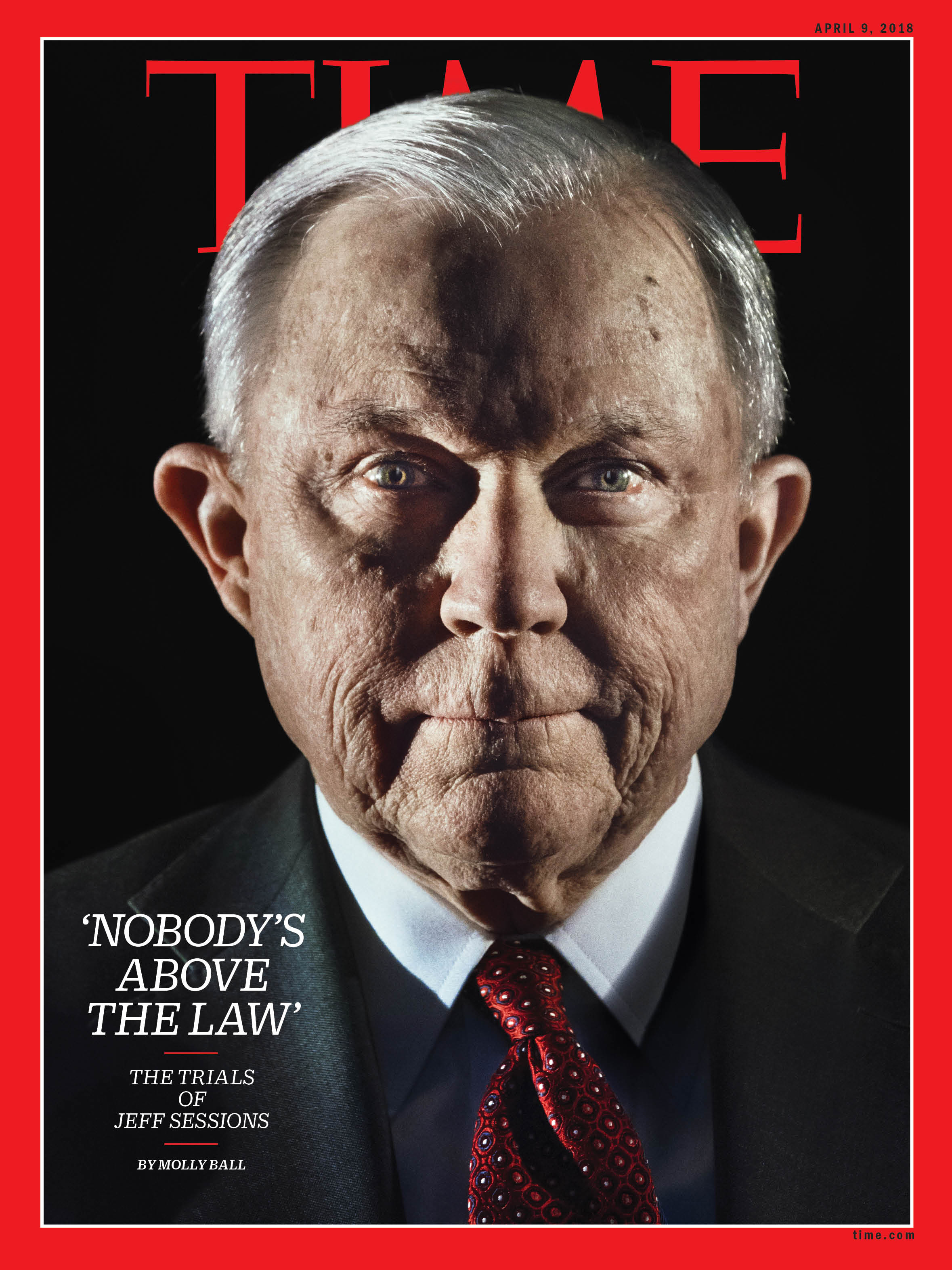

Sessions’ ultimate loyalty, he told me, is not to any man but to a principle. “Congress passes a law, judges follow the law, and nobody’s above the law, including the judges, and including the President,” he said. Yet every person of conviction makes a bargain by going to work for Trump: to wield the levers of power, to make changes you believe are for the better, you will have to make certain compromises. As many others can attest–and as Sessions may soon discover–following Trump can lead you astray.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Molly Ball at molly.ball@time.com