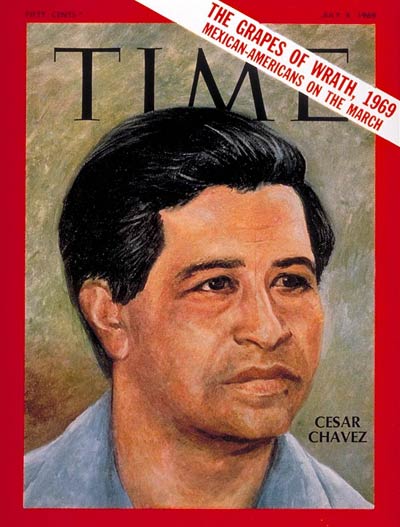

When TIME Magazine ran a cover story in 1969 about the then-ongoing grape boycott, organized in part by the United Farm Workers in an effort to address working conditions among the laborers who picked those grapes in California, Dolores Huerta was there — sort of.

She was described in the story as the “tiny, tough assistant” of UFW leader Cesar Chavez. In reality, however, while Chavez was the head of the organization, Huerta was far more than an assistant. She and Chavez worked together in laying the groundwork for the union in the late 1950s and early 1960s. She worked directly with the farmworkers for whom the group advocated, and also in the state capital as their legislative advocate. She risked her life for her activism, is credited with coining the slogan “Yes, we can,” and along the way raised 11 children, many of whom have become activists in their own rights. In 2012, she received the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

The question of how such an important figure in 20th century history could be seen as a mere assistant is a central theme of the documentary Dolores, which has its PBS premiere on Tuesday night. With the film’s Independent Lens debut on the horizon, the 87-year-old activist spoke to TIME about what it was like to be a woman leading a labor movement in the 1960s, and what comes next.

One of the main theses of this film is that you didn’t get credit for the work you did to organize the farmworkers. What did you think of that as the focus of the movie? Did you feel overlooked at the time?

I never felt overlooked because I didn’t expect any kind of recognition. I think that’s very typical of women. I had been acculturated to be supportive, to be accommodating, to support men in the work they do. We never think of getting credit or recognition or even taking the power. We didn’t think it those terms. Of course I think that’s changing now and there’s a surge of women who are not only running for office, but getting elected. That could make an incredible amount of difference in our world. We will never have peace in the world until feminists take power.

How would you define what it means to be a feminist?

To me, a feminist is a person who supports a woman’s reproductive rights, who supports a woman’s right to an abortion, who supports LGBT rights, who supports workers and labor unions, somebody who cares about the environment, who cares about civil rights and equality and equity in terms of our economic system. That is a feminist. And of course we know that there are many men who are feminists as well as women.

The film covers a little bit of the moment where you see the link between what you’re working on with the farmworkers and the feminist movement of the time, and the question of whether there was room in the feminism of the 1960s for the women for whom you advocated. Were there any particular moments that made you feel excluded or included?

I have never felt excluded. My mother was a feminist. She was a business woman. She was a dominant force in our family. But when I went to work with the farmworker’s union as an organizer, I kind of had to subdue my feminist tendencies in that respect. Women of color have always been in the forefront, of the civil rights movement and of the labor movement, but when you think about the feminist movement, it was originally organized by middle-class women. That’s why a lot of people have that narrative that feminism is for white women. Lots has been made out of that, but I think sometimes that’s not really fair. That’s the way that it was. But I don’t think the feminist movement was meant to exclude any people of color.

When TIME selected the people speaking out about sexual harassment and assault to be 2017’s Person of the Year, there was a line in the story about farmworkers marching in solidarity with Hollywood actors. When did you first become aware of sexual harassment as an issue affecting farmworkers?

Farmworker women have always been subjected to sexual harassment and rape. The women would have to have sex with the foremen to make sure that they kept their jobs. It was their form of job security to have children by these guys. The thing is, a lot of time you have farmworkers who work as families, so there’s a lot of fear, because if the woman reports sexual harassment from the foreman, then maybe the whole family will get fired. There’s also a threat of violence because her partner could feel that she was responsible for the come-ons, and she could then face violence at home. Also they work out in the fields and they’re kind of isolated. In California, because of the work we did with the farmworkers’ union, the Agricultural Labor Relations Board has included training on sexual harassment as part of the work that they do.

Was that something people were talking about early in this work, or was it hush-hush?

I think people talked about it amongst themselves, and of course we did a lot of work when I worked with the farmworkers’ union to get women to come out and report sexual harassment. Luckily in California, women are able to report sexual harassment and they don’t have to do it openly, they can do it privately.

Both in the new interviews conducted for this movie and also in older footage of you, there’s a lot of discussion of the ways you balanced motherhood and your work—but Cesar Chavez had children too and you don’t see people asking him about that.

Cesar’s wife Helen did work for a credit union, but she didn’t have to travel like I did, like with the grape boycott, so Cesar’s kids had a kind of happy-mom-at-home-all-the-time experience.

Did anyone ask him or other men you worked with about their choice to focus on their work rather than spending that time with their families?

Probably not. The thing about that is that every single mother in every single working family has that question every single day. Who am I going to leave my children with? Are they going to be safe? Are they going to be protected? That’s something women have to deal with all the time. Watching the movie I thought to myself, wait a minute, this is something we have to advocate for. We have to make sure that the children are not only safe while the families are working, but also that they’re getting a good education. In the movie, they made a big deal out of [how my work affected my children], but what they didn’t say in the movie was that we had a daycare center in the union hall for the mothers on the picket line. We had the first farmworker daycare in the state of California.

I went back and looked at the cover story in TIME about the grape boycott in 1969 and it makes the interesting point that the grape growers saw a labor dispute, but the workers saw it as a cultural cause about pride and identity. How did the farmworkers’ cause first become linked to the larger issue of Latino identity?

I think it was inherent in the way the farmworkers were left out of the National Labor Relations Board to begin with. When they [created] the NLRB back in the 1930s, the farmworkers and domestic workers were left out of the law. They were people of color. They were Mexicans and African-Americans. So right at the instant of that it became a civil rights movement. When you think of the fact that they denied the farmworkers toilets in the field, it was the worst kind of brutal discrimination. A lot of this is very racial, about the way the workers were treated. Remember in the South, even as recently as the ‘60s when we organized in Florida, the majority of the farm workers there were African-Americans and people from the islands.

At the time, how did you make that connection for the workers, between their labor rights and their identities?

That’s something that they lived every day of their lives out in the fields. When I came to work with farmworkers — just the fact that I was with them — I was treated differently than when I came forward as a middle-class schoolteacher. When I was in Sacramento as the political director for the United Farm Workers and for the Community Service Organization, you’d have the representatives of the [grape] growers in front of a legislative committee, and they would say, ‘We do these people a favor because they’re a bunch of winos, alcoholics, and nobody will hire them.’ This is the picture that they gave of the farmworkers. I remember going up to this one guy and saying, ‘If you ever say that about farmworkers again I will go out there and talk about how you are a bunch of racists,’ so he changed his tune.

Where do you see American activism going next?

I think we’re in a critical moment. We have all of these tools that are accessible to us now. All this knowledge we have, they can’t hide to truth from us. But at the same time, I’ve been following the movie around this country this last year just to get across this notion that we have to end racism, we have to end misogyny, we have to end homophobia, we have to end bigotry and looking down on our working people. We have to do it through our educational system. We’ve got to include, from pre-K, the contributions of people of color in our schools today, beginning with Native Americans, whose land we took and have never compensated them for, to the African slaves who built the White House and Congress, and then the immigrants who came from Mexico and tilled the land and built the railroads and then the Japanese, the Chinese, people from India, the Latinos, all these people who built the infrastructure of our country. And the contributions of the labor movement! How many people know how we got to eight-hour days? This should all be included in our educational system, so we can get a big giant eraser and erase the ignorance that we have right now in the United States of America.

This interview has been edited and condensed.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Inside Elon Musk’s War on Washington

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Cecily Strong on Goober the Clown

- Column: The Rise of America’s Broligarchy

Write to Lily Rothman at lily.rothman@time.com