When Stephanie Clifford appears on CBS’ 60 Minutes on Sunday, the woman known in her porn career as Stormy Daniels, will be adding a chapter to a very long history of the American public’s fascination with Presidents’ private lives.

Clifford is not the only woman who says she had an affair with President Donald Trump before he took the office — Anderson Cooper recently interviewed former Playboy model Karen McDougal about something similar — but this story is much older than just a decade or so. In some ways, it goes back more than 200 years.

For about as long as the country has existed, the public and the press have imposed few consequences on Presidents for what they do behind closed doors, even when those actions become public, as long as those actions don’t affect the rest of the government. What has changed is the perception of when that line gets crossed.

Early Scandals

In the nation’s earliest years, newspapers were associated with political parties, so accusations of infidelity were often brought up to slam political opponents but dismissed by loyalists. “The golden age of America’s founding was also the gutter age of American reporting,” as pundit Eric Burns put it in his book Infamous Scribblers: The Founding Fathers and the Rowdy Beginnings of American Journalism.

The most notorious scandalmonger of that period was James Callender, a Federalist newspaper editor, who, for example, spread stories of Thomas Jefferson’s fathering children with Sally Hemings, a woman enslaved at his estate, and also making a move on the wife of his good friend from college. Of the latter accusation, Jefferson wrote in a July 1, 1805, letter to his Secretary of the Navy Robert Smith, “I plead guilty to one of their charges, that when young & single I offered love to a handsome lady. I acknolege it’s incorrectness; it is the only one, founded in truth among all their allegations against me.” (However, Monticello, the museum at the site of his former home, now acknowledges that the charge about Hemings is true too.)

But such claims about Jefferson didn’t seriously damage his career. The times when personal stories like those did make a difference was when there was concern over whether public figures’ personal lives affected their jobs.

The most famous political sex scandal Callender revealed was the extramarital affair that Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton — who wasn’t president, but proves the point — had with Maria Reynolds between 1791 and 1792, details of which Callender published in his anthology The History of the United States for 1796. In that case, it wasn’t the affair that was controversial so much as the concern that Hamilton may have used federal funds to pay hush money to her husband. In a 1797 pamphlet, he attempted to set the record straight, clarifying that while the affair was shady, he didn’t do anything illegal.

Historian David Eisenbach, an author of One Nation Under Sex: How the Private Lives of Presidents, First Ladies and Their Lovers Changed the Course of American History, argues that examining presidents’ personal lives was also a way to judge “how someone would behave in office,” in the absence of other information about their character: “In European countries, politicians came from distinguished families, but in America, you didn’t have the old families to rely upon.”

This was particularly true for candidates who came from humble backgrounds, such as Andrew Jackson. During his rise to power, the media drew conclusions about his fitness for office from speculation on the legality of his marriage. During the 1828 election, John Quincy Adams’ campaign is said to have helped spread speculation about whether he and his wife eloped while she was still married to her first husband, in an attempt to prove that Jackson lacked a moral compass. First-Lady-elect Rachel Jackson died shortly before Jackson’s inauguration, and it’s believed that her stress over the public dissection of their marriage had exacerbated her ailments.

But, again, the charges against Jackson’s marriage didn’t actually keep him from office — and in some cases such uproar could actually help.

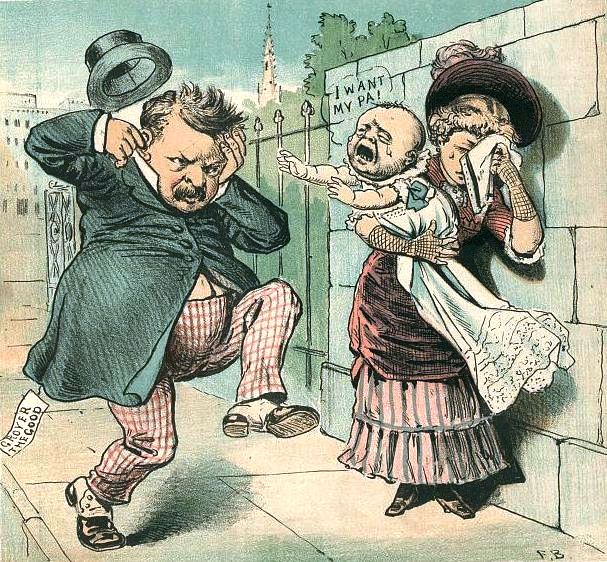

For example, Grover Cleveland is believed to have won the 1884 presidential election in part because of the grace under pressure he exhibited after a Buffalo newspaper revealed that he had fathered a child out of wedlock. The story was made famous by a Sep. 27, 1884, editorial cartoon published about a month before Election Day, which gave rise to the “Ma, Ma, Where’s My Pa?” chant at rallies for his opponent James Blaine. But he was above-board about the issue, and ordered party leaders to tell the truth, including about the child support that he paid. The decision reflected well on him, and he became President.

Turning a Blind Eye

The period around the turn of the 20th century marked a major change in journalism, as it became professionalized — with trade organizations and professional schools — and, in many cases, divorced from outright association with a political party. As part of that reform, journalists backed off their scrutiny of presidents’ personal lives.

In fact, one of Warren Harding’s mistresses couldn’t even find anyone to publish her tell-all about her sexual relationship. It was after his death that Nan Britton published The President’s Daughter, which is considered one of the first graphic tell-all political memoirs. As the title suggests, she claimed she gave birth to a child that was his in 1919 — a claim that DNA testing appeared to confirm in 2015. Evidence of the affair was in a trove of explicit letters that a historian found in the early ’60s. His family, however, successfully sued to keep them sealed until 2014.

The press likewise stayed away from President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s relationship with Lucy Mercer, Eleanor Roosevelt’s social secretary, and President John F. Kennedy was spared scrutiny of his trysts, too — or rather his “extracurricular screwing around” as Ben Bradlee, the Washington Post editor of Pentagon Papers fame, once put it.

The reasons for keeping a lid on presidents’ personal lives were many. For one thing, some of the predominantly male political journalists could be seen as hypocrites if they made a big deal out of presidents’ affairs.

“Many of the men in the White House press corps were carrying on dalliances of their own, so if they went public with the President, there would be blowback, and their wives would find out,” says Barbara Perry, the Director of Presidential Studies at the University of Virginia’s Miller Center of Public Affairs, who spoke to TIME as part of a new presidential-history partnership between TIME History and the Miller Center.

But it’s significant to note that — perhaps not coincidentally, given the lives of those shaping the media narrative — those dalliances weren’t generally seen as affecting the public at all. They were secret, but also trivial.

The writer Marvin Kalb once recalled a night in 1963 when he was covering one of President Kennedy’s New York visits for CBS, and was tackled by a Secret Service agent right outside an entrance to Kennedy’s private elevator at the Carlyle Hotel. While on the floor, he looked up and caught a glimpse of a woman going into the private elevator. He did not even consider pursuing the story. “In those days, the possibility of a presidential affair, while titillating, was not considered ‘news’ by the mainstream press — not when the Cuban missile crisis was still a fresh and frightening memory of the nuclear dangers of the Cold War, not when racial tensions were again clawing at the soul of the nation,” he wrote.

The moral panic of the 19th century had faded, and concerns about the possibility of harassment had not yet come up on a major scale. So the affairs stayed secret — even when, in some cases, they did have implications for government or security. For example, though one of Harding’s mistresses couldn’t find a publisher, it was later revealed that the Republican National Committee had to pay hush money to another mistress of his.

The Public Should Know

In the late 20th century, things changed again. In 1969, after Teddy Kennedy drove a car into the water off Chappaquiddick, leading to the death of his passenger Mary Jo Kopechne, a TIME essay posited that the public was asking about what public figures did in their private lives because those figures had gotten more powerful, so it mattered more. In general, that was true — the office of the President became more powerful in the 20th century than it had previously been — but perhaps the bigger change was in the perception of what truly qualified as private. The things that were secret were no longer seen as quite so meaningless to politics.

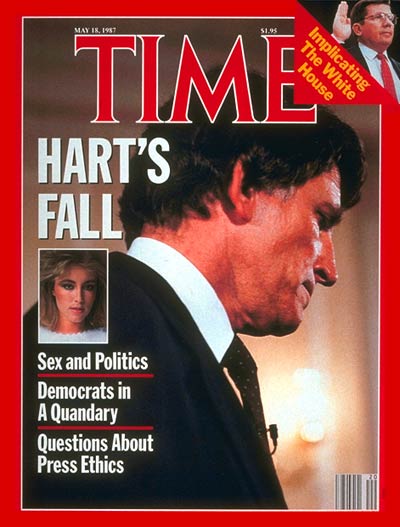

That difference was thrown into relief in 1987, when Colorado Senator Gary Hart was the frontrunner for the 1988 Democratic presidential nomination. He told New York Times reporter E.J. Dionne that he didn’t care if people followed him around, and that anyone who did so would be very bored. So the Miami Herald staked out his Washington townhouse until they got a photo of Hart with Donna Rice, a 29-year-old Miami model who was not his wife. Two days after refusing to answer a Washington Post reporter’s question, “Have you ever committed adultery?” at a televised press conference, he suspended his campaign.

TIME’s cover story on Hart’s fall from grace cited the Herald’s stakeout as “a watershed moment in political journalism.” It wasn’t just a matter of public willingness to talk about sex or the fact that Hart had been caught in hypocrisy, the story pointed out: “[With] the changing status of women, society has grown less tolerant of the macho dalliances of married men.” (It’s worth remembering, as TIME pointed out in that 1969 essay, that when scandal helped bolster Cleveland, women couldn’t even vote.)

That shifting line — the shared feeling that it doesn’t necessarily matter what the President does in private, but that some things that seem private really aren’t — is also illustrated by what is probably the 20th century’s most famous White House sex scandal: President Bill Clinton’s affair with White House intern Monica Lewinsky. With Clinton, it wasn’t the affair itself but rather the attempt to cover it up that would lead to his impeachment, points out political scientist Alison Dagnes, co-editor of Sex Scandals in American Politics. Clinton’s job approval ratings remained consistently high during the scandal, suggesting that the public didn’t think it was affecting the way he did his job. “People felt good about where they were and where America was in the world and gave Clinton credit for that,” Perry explains.

It has been more recently, as public conversations about sex in the workplace have evolved, that some have come to rethink the implication of a relationship between a President and an intern, and the power dynamics entailed.

Throughout, from Jefferson to Clinton, the takeaway is the same: when the public thinks that the President’s private life will get in the way of governing — whether as a matter of 19th-century morals or 20th-century gender dynamics — such a scandal can truly damage a presidency. If there’s no perception that an affair or similar scandal will impact the government, historically the political fallout has been minor. The real change has been that what people do in private has once again, over the last few decades, come to be seen as relevant to a person’s fitness to lead.

So what does that mean for Trump?

He may actually benefit from the fact that — given that a range of sexual misconduct allegations already surfaced during his campaign, and just this past week a judge ruled that Apprentice contestant Summer Zervos, who claims that Trump groped her, can move forward with her defamation suit — claims of consensual affairs may not change public opinion in any significant way, though that could change if campaign-funding laws get drawn in.

“There is a genius in Trump’s run for the presidency in that he starts with the premise that all politicians are crooked, and I’m not one, so you don’t need to judge me the way you judge politicians,” Perry points out.

Historian Thomas A. Foster, author of Sex and The Founding Fathers, suggests looking not at what the President does but how his actions compare to his reputation. Shock and hypocrisy, he argues, are more damaging than adultery. Trump — who has owned beauty pageants and has been married three times — built his brand partially on his virility and what Foster calls an emphasis on “conquests.” Now it remains to be seen how he will conquer these most recent allegations.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Olivia B. Waxman at olivia.waxman@time.com