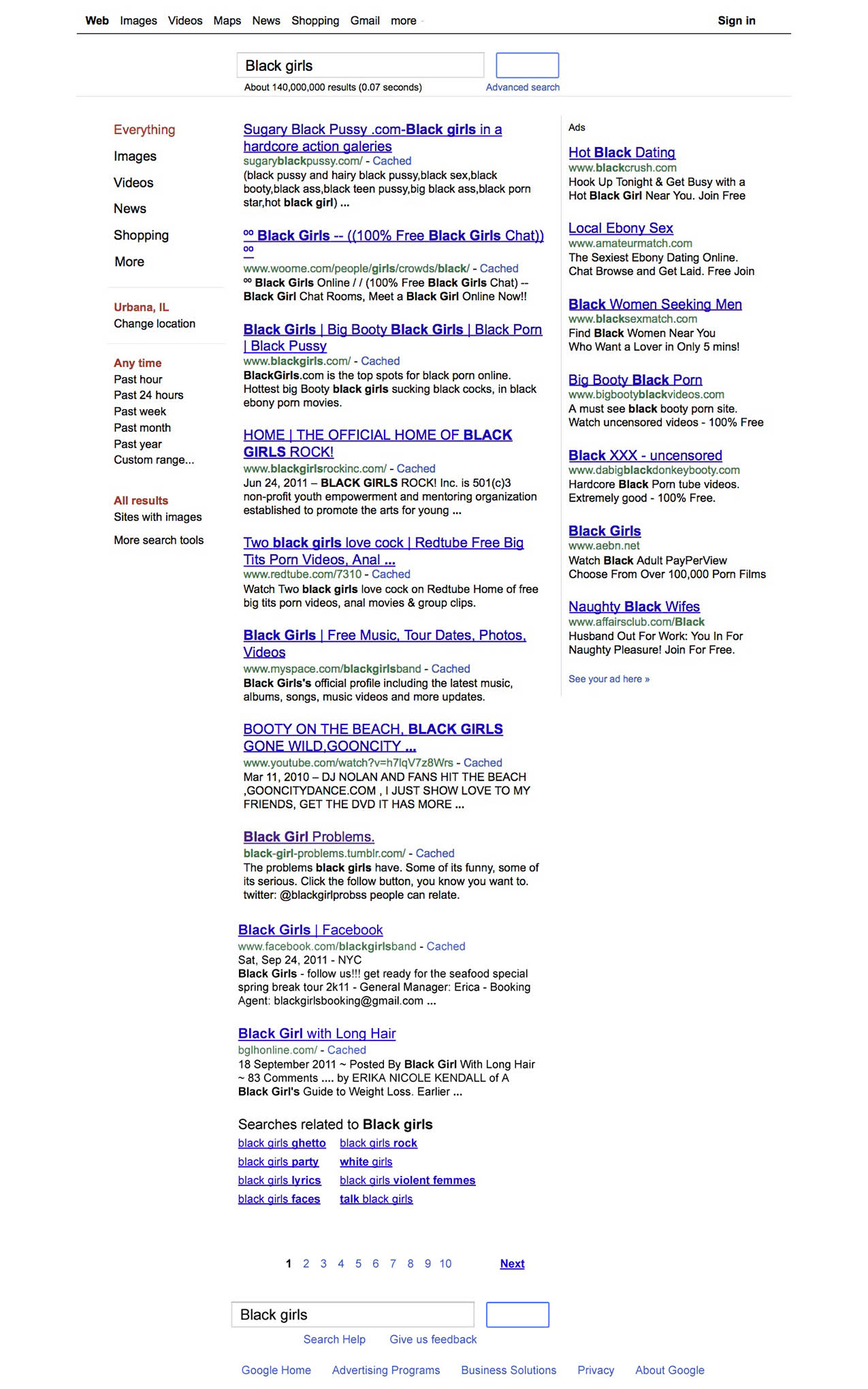

My first encounter with racism in search was in 2009 when I was talking to a friend who causally mentioned one day, “You should see what happens when you Google ‘black girls.’” I did and was stunned.

These are the details of what a search for “black girls” would yield for many years, despite that the words “porn,” “pornography,” or “sex” were not included in the search box. In the text for the first page of results, for example, the word “p-ssy,” as a noun, is used four times to describe black girls. Other words in the lines of text on the first page include “sugary” (two times), “hairy” (one), “sex” (one), “booty/ass” (two), “teen” (one), “big” (one), “porn star” (one), “hot” (one), “hard- core” (one), “action” (one), “galeries [sic]” (one).

It was troubling to realize that I had undoubtedly been confronted with the same type of results before but had learned, or been trained, to somehow become inured to it, to take it as a given that any search I might perform using keywords connected to my physical self and identity could return pornographic and otherwise disturbing results. Why was this the bargain into which I had tacitly entered with digital information tools? And who among us did not have to bargain in this way? As a black woman growing up in the late 20th-century, I also knew that the presentation of black women and girls that I discovered in my search results was not a new development of the digital age. I could see the connection between search results and tropes of African Americans that are as old and endemic to the United States as the history of the country itself. My background as a student and scholar of Black studies and Black history, combined with my doctoral studies in the political economy of digital information, aligned with my righteous indignation for black girls everywhere. That first search in 2009 launched a years-long research process, following offenses and “fixes” through 2016. I had to search on.

Commerce and creators

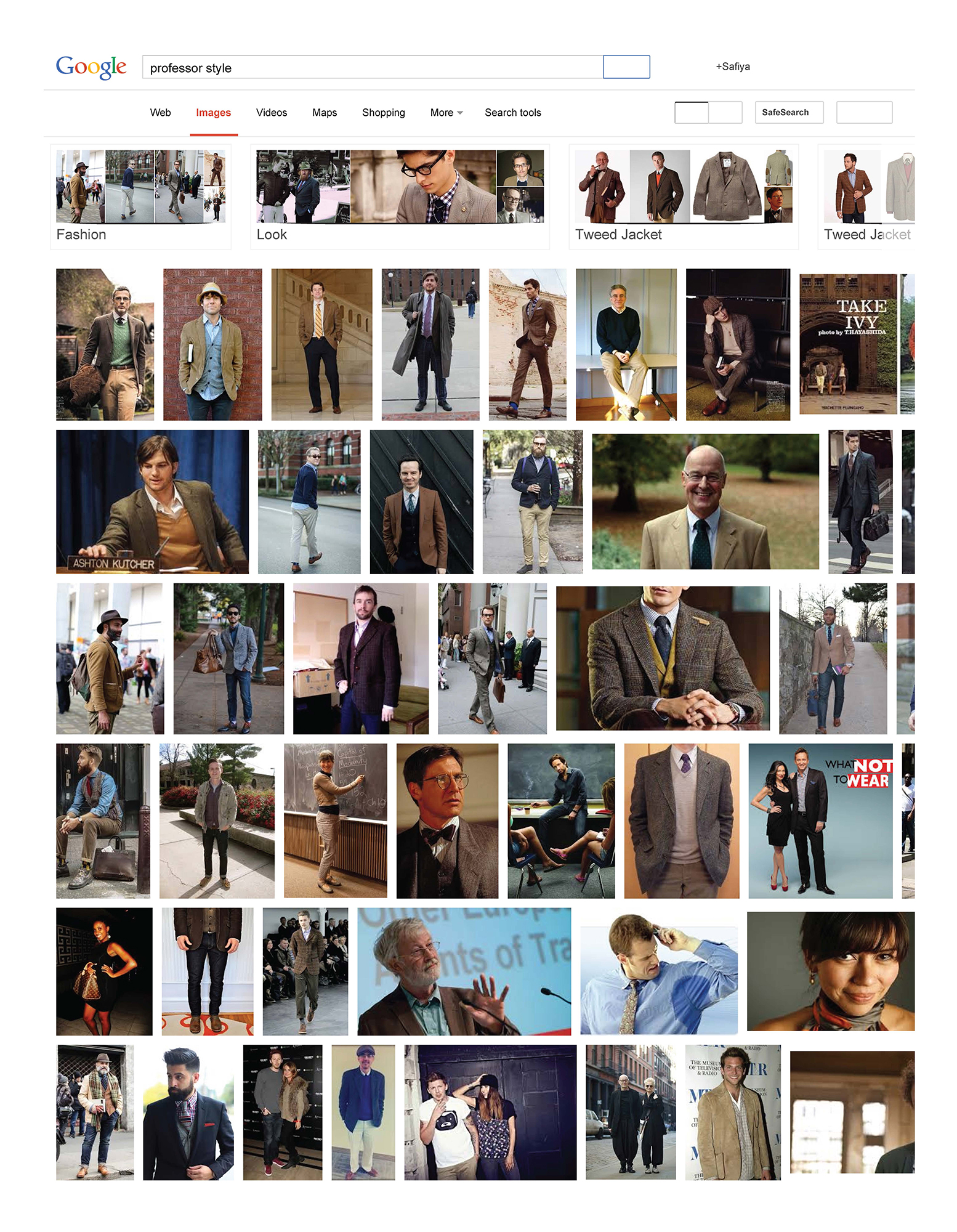

Information monopolies such as Google have the ability to prioritize web search results on the basis of a variety of topics, such as promoting their own business interests over those of competitors or smaller companies that are less profitable advertising clients than larger multinational corporations are. In this case, the clicks of users, coupled with the commercial processes that allow paid advertising to be prioritized in search results, mean that representations of women are ranked on a search engine page in ways that underscore women’s historical and contemporary lack of status in society — a direct mapping of old media traditions into new media architecture. What each search represents is Google’s algorithmic conceptualizations of a variety of people and ideas. Whether looking for autosuggestions or “answers” to various questions or looking for notions about what is beautiful or what a professor may look like (which does not account for people who look like me who are part of the professoriate — so much for “personalization”), Google’s dominant narratives reflect the kinds of hegemonic frameworks and notions that are often resisted by women and people of color. We must interrogate what advertising companies serve up as credible information, rather than have a public instantly gratified with stereotypes in three-hundredths of a second or less.

In the case of that first page of results on “black girls,” I clicked on the link for both the top search result (unpaid) and the first paid result, which is reflected in the right-hand sidebar, where advertisers that are willing and able to spend money through Google AdWords have their content appear in relationship to these search queries. Advertising in relationship to black girls for many years has been hypersexualized and pornographic, even if it purports to be just about dating or social in nature. (Google didn’t block explicit content from AdWords until 2014.)

Published text on the web can have a plethora of meanings, so in my analysis of all of these results, I have focused on the implicit and explicit messages about black women and girls in both the texts of results or hits and the paid ads that accompany them. By comparing these to broader social narratives about black women and girls in dominant U.S. popular culture, we can see the ways in which search engine technology replicates and instantiates these notions. This is no surprise when black women are not employed in any significant numbers at Google. Not only are African Americans underemployed at Google, Facebook, Snapchat and other popular technology companies as computer programmers, but also jobs that could employ the expertise of people who understand the ramifications of racist and sexist stereotyping and misrepresentation and that require undergraduate and advanced degrees in ethnic, Black/African American, women and gender, American Indian, or Asian American studies do not exist.

One cannot know about the history of media stereotyping or the nuances of structural oppression in any formal, scholarly way through the traditional engineering curriculum of the large research universities from which technology companies hire across the United States. Ethics courses are rare, and the possibility of formally learning about the history of black women in relation to a series of stereotypes such as the Jezebel, Sapphire and Mammy does not exist in mainstream engineering programs. I can say that when I taught engineering students at UCLA about the histories of racial stereotyping in the U.S. — and how these are encoded in computer programming projects — my students left the class stunned that no one had ever spoken of these things in their courses. Many were grateful to at least have had 10 weeks of discussion about the politics of technology design, which is not nearly enough to prepare them for a lifelong career in information technology. We need people designing technologies for society to have training and an education on the histories of marginalized people, at a minimum, and we need them working alongside people with rigorous training and preparation from the social sciences and humanities. To design technology for people, without a detailed and rigorous study of people and communities, makes for the many kinds of egregious tech designs we see that come at the expense of people of color and women.

Beyond black girls

Although I focus mainly on the example of black girls to talk about search bias and stereotyping, black girls are not the only girls and women marginalized in search. The results retrieved two years into this study, in 2013, representing Asian girls, Asian Indian girls, Latina girls, white girls, and so forth reveal the ways in which girls’ identities are commercialized, sexualized or made curiosities within the gaze of the search engine. Women and girls do not fare well in Google Search — that is evident.

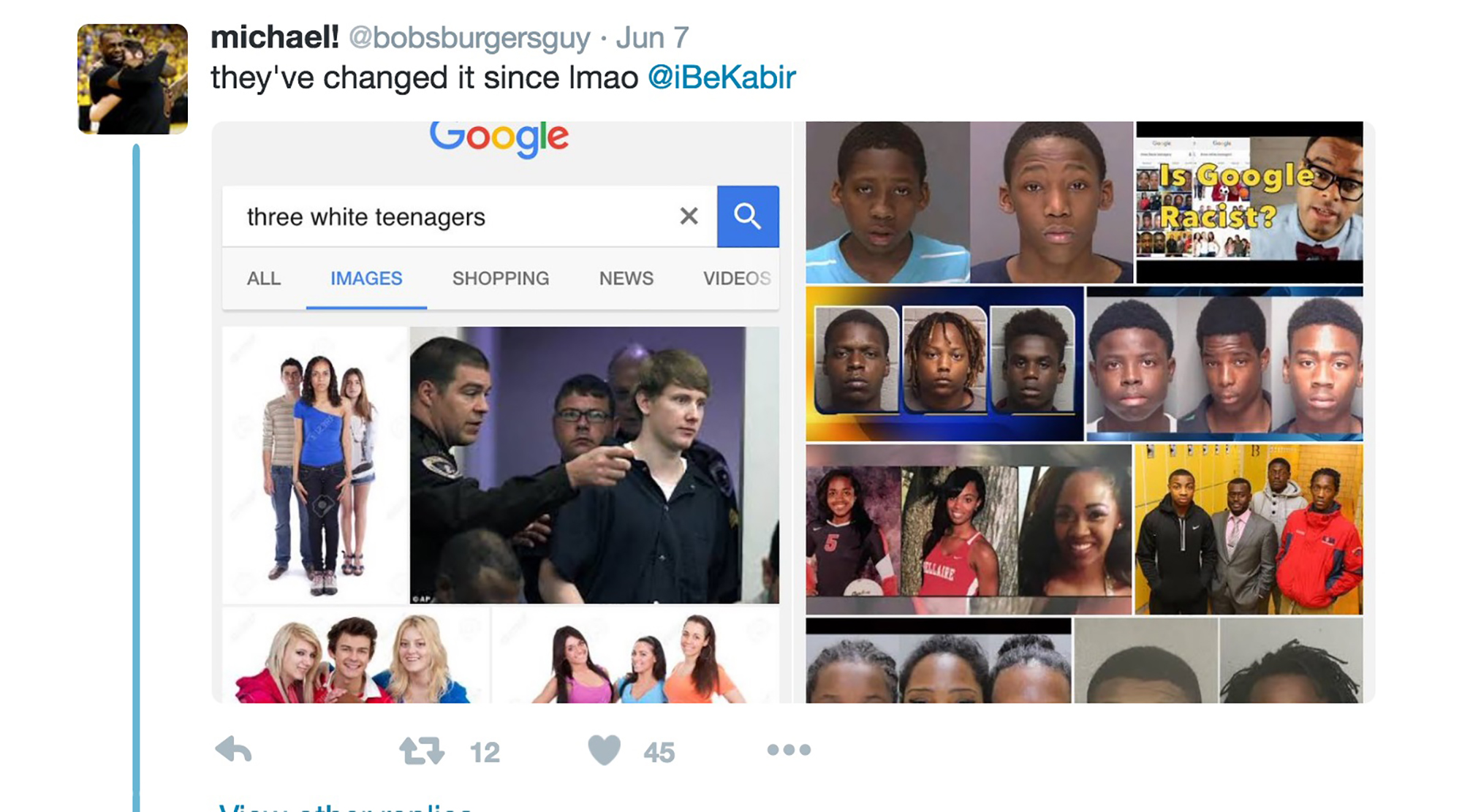

Of course, these problems extend to non-gendered racism, as well. On June 6, 2016, Kabir Ali, an African American teenager from Clover High School in Midlothian, Va., tweeting under the handle @iBeKabir, posted a video to Twitter of his Google Images search on the keywords “three black teenagers.” The results that Google offered were of African American teenagers’ mug shots, insinuating that the image of Black teens is that of criminality. Next, he changed one word — “black” to “white” — with very different results. “Three white teenagers” were represented as wholesome and all-American. The video went viral within 48 hours, and Jessica Guynn, from USA Today, contacted me about the story. In typical fashion, Google reported these search results as an anomaly, beyond its control, to which I responded, “If Google isn’t responsible for its algorithm, then who is?” One of Ali’s Twitter followers later posted a tweak to the algorithm made by Google on a search for “three white teens” that now included a newly introduced “criminal” image of a white teen and more “wholesome” images of black teens.

What we know about Google’s responses to racial stereotyping in its products is that it typically denies responsibility or intent to harm, but then it is able to “tweak” or “fix” these aberrations or “glitches” in its systems.

What we need to ask is why and how we get these stereotypes in the first place and what the attendant consequences of racial and gender stereotyping do in terms of public harm for people who are the targets of such misrepresentation. Images of white Americans are persistently held up in Google’s images and in its results to reinforce the superiority and mainstream acceptability of whiteness as the default “good” to which all others are made invisible. There are many examples of this, where users of Google Search have reported online their shock or dismay at the kinds of representations that consistently occur. Meanwhile, when users search beyond racial identities and occupations to engage concepts such as “professional hairstyles,” they have been met with the kinds of images seen below. The “unprofessional hairstyles for work” image search, like the one for “three black teenagers,” went viral in 2016, with multiple media outlets covering the story, again raising the question, can algorithms be racist?

Where are black girls now?

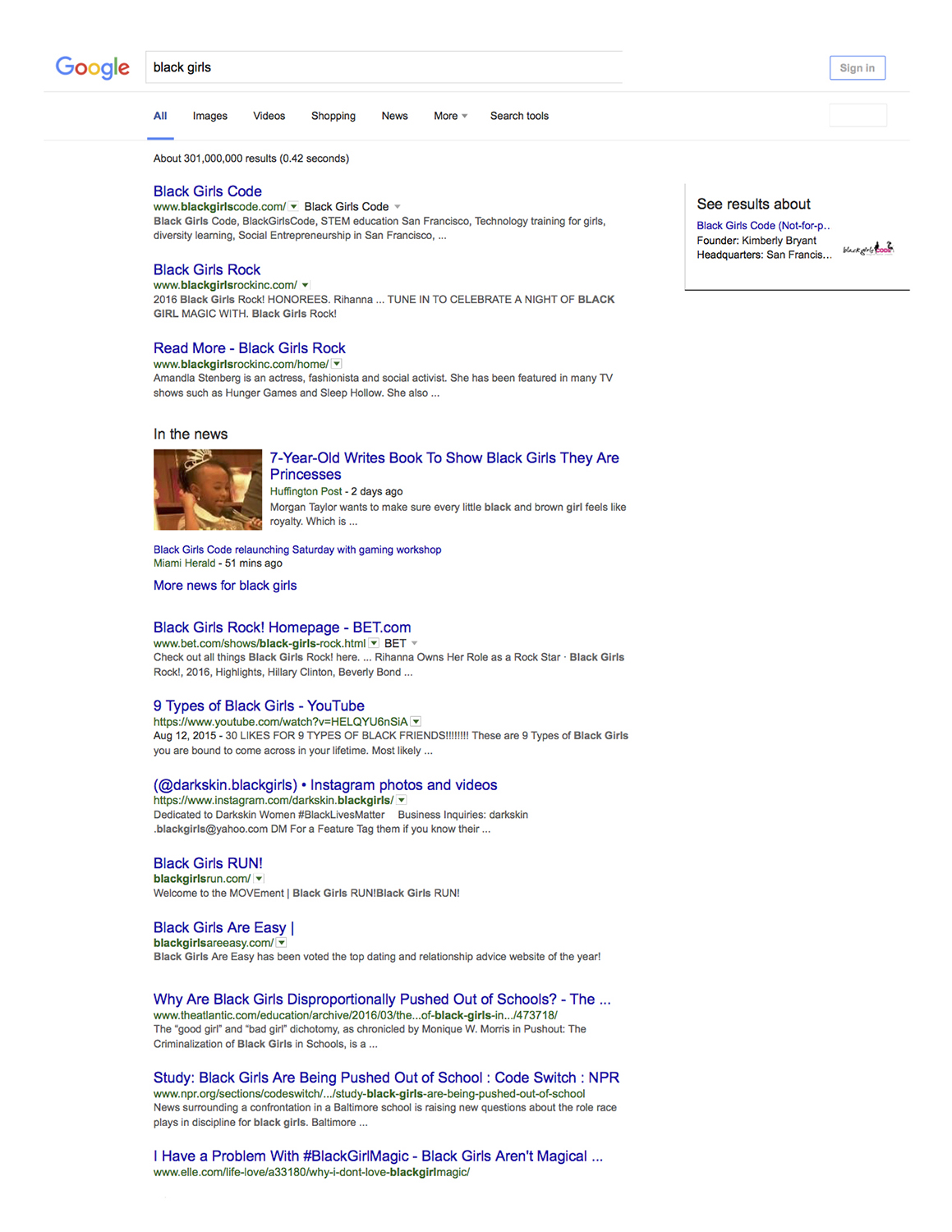

Since I began the pilot study in 2010 and collected data through 2016, some things have changed. In 2012, I wrote an article for Bitch Magazine, which covers popular culture from a feminist perspective, after some convincing from my students that this topic is important to all people — not just black women and girls. I argued that we all want access to credible information that does not foster racist or sexist views of one another. I cannot say that the article had any influence on Google in any definitive way, but I have continued to search for black girls on a regular basis, at least once a month, and I can report that Google had changed its algorithm to some degree about five months after that article was published. After years of featuring pornography as the primary representation of black girls, Google made modifications to its algorithm, and the results as of the conclusion of this research can be seen here:

No doubt, as I speak around the world on this subject, audiences are often furiously doing searches from their smart phones, trying to reconcile these issues with the momentary results. Some days they are horrified, and other times, they are less concerned, because some popular and positive issue or organization has broken through the clutter and moved to a top position on the first page. Indeed, as my book was going into production, news exploded of biased information about the U.S. presidential election flourishing through Google and Facebook, which had significant consequences in the political arena.

I encourage us all to take notice and to reconsider the affordances and the consequences of our hyper-reliance on these technologies as they shift and take on more import over time. What we need now, more than ever, is public policy that advocates protections from the effects of unregulated and unethical artificial intelligence.

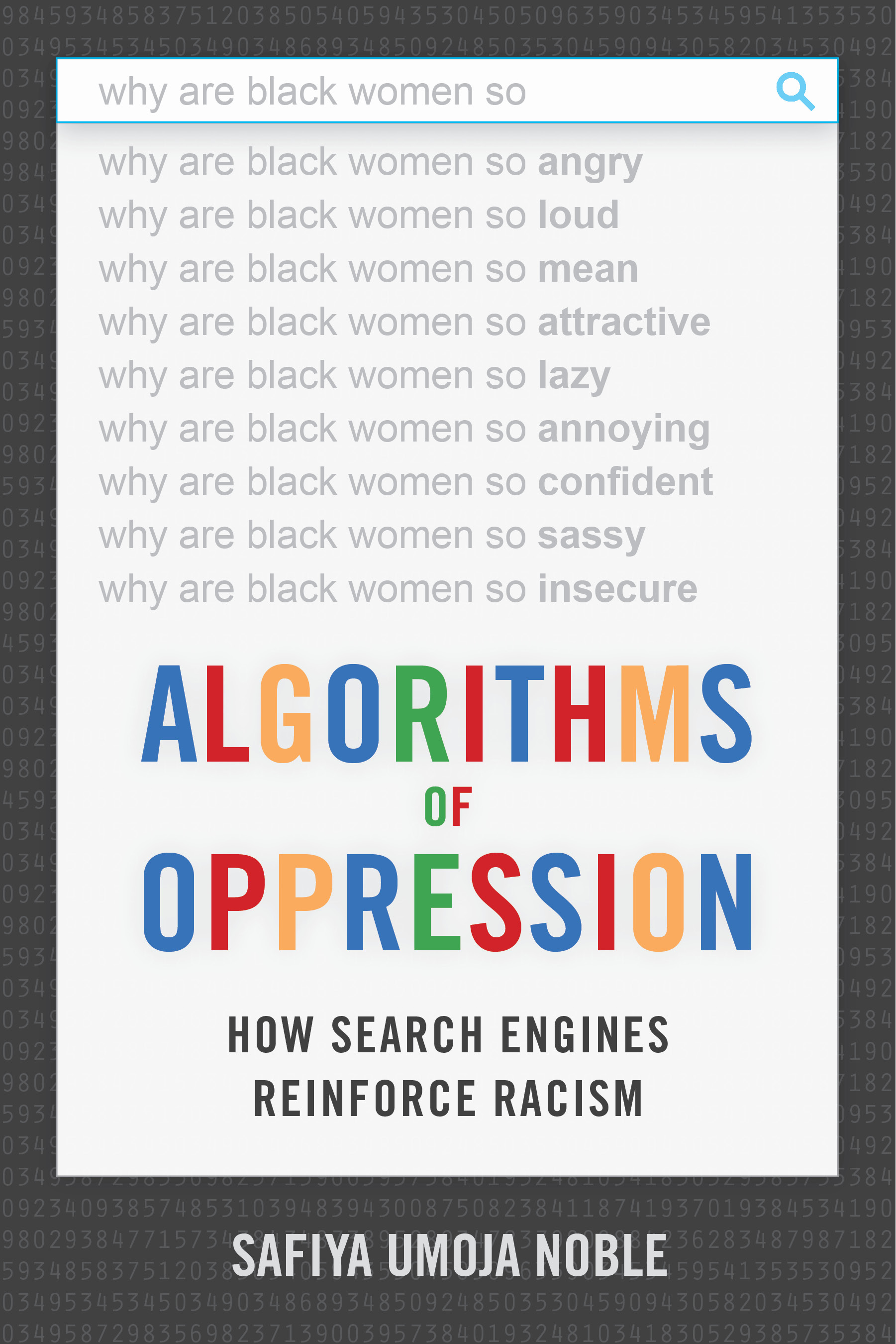

From Algorithms of Oppression: How Search Engines Reinforce Racism by Safiya Umoja Noble. Reprinted with permission by NYU Press (c) 2018.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- How Elon Musk Became a Kingmaker

- The Power—And Limits—of Peer Support

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com