In the corner of a Baghdad living room sits an unusual piece of decor—a sizable bust of Saddam Hussein’s head, staring implacably out with a military beret on his head. Its owner, politician Mowaffak al-Rubaie, has placed a length of rope around its neck. It’s the same rope that was used to hang Saddam on Dec. 30, 2006, according to al-Rubaie, who claims that he was charged with pulling the lever that night.

There’s no way to verify his story. Other accounts have a guard pulling the lever, and it’s impossible to prove this is the rope that hanged the dictator. Nonetheless, al-Rubaie—a neurologist and surgeon who had been imprisoned and tortured three times under the dictator who ruled Iraq for 24 years—knew how he wanted to display it. “It seemed the best place to put the rope was around his neck,” he says.

Al-Rubaie was in exile in London until shortly after March 20, 2003, the date exactly 15 years ago when U.S. aircraft pummeled Baghdad, marking the first moments of the Iraq War. Within weeks, Saddam Hussein’s 24-year dictatorship collapsed, and the U.S. military occupied the country, beginning what would be America’s deadliest intervention since the Vietnam War. Nearly 4,500 Americans have died in Iraq in the years since, and hundreds of thousands of Iraqi lives have been lost.

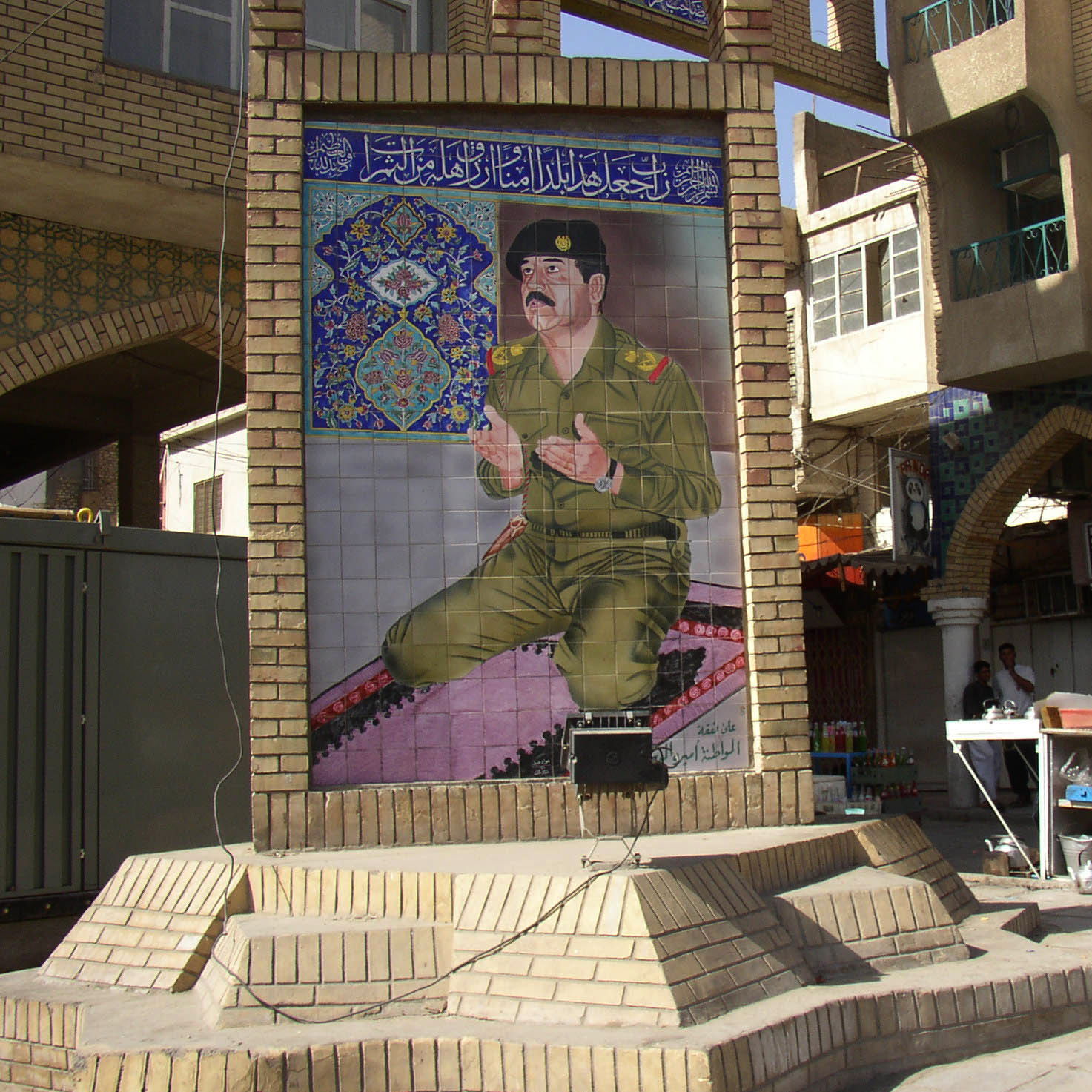

Something else was lost in the chaotic war: The countless statues, murals, paintings, mosaics and artifacts that featured Saddam, whose image had for years peered down from every office wall, building, and town square across Iraq, reminding citizens not to dare challenge his iron rule. Within days of the U.S. invasion, Iraqis had smashed and sliced those statues and paintings, in an explosion of fury against the ruthless autocrat. When U.S. Marines reached central Baghdad on April 9, 2003, they toppled the giant Saddam statue in the city’s Firdos Square.

I was deeply familiar with those Saddam paintings, having reported in Iraq several times during his suffocating presidency. Perhaps sensing that the dictatorship was heading for collapse, I snapped dozens of photos of Saddam. Among them are artworks that are now destroyed, including a giant tiled mural of a smiling, waving Saddam in his home town of Tikrit, on the day he won 100% approval in a bogus referendum in October, 2002. Another scene shows the marble entryway of the Al Rasheed Hotel in Baghdad, which until the U.S. invasion in 2003 featured former U.S. President George H.W. Bush with the words “Bush is criminal;” visitors would wipe their feet on his face.

It was simply impossible to destroy all the Saddam paintings, however. And amid the chaos, both U.S. soldiers and Iraqis squirreled away Saddam statues and paintings—some for possible monetary gain, and others as war souvenirs or as historical artifacts.

As U.S. forces rolled into Iraq and Saddam’s forces collapsed, I drove into Iraq from Jordan, and found in the trashed VIP lounge of the border post an oil painting lying amid the detritus on the floor, showing Saddam, resplendent in desert robes; I pried it off its frame, and stuck the rolled up canvas in my bag—an act, I thought, of saving history from being entirely obliterated.

Al-Rubaie, who today has become a high-ranking politician in Baghdad, is doing much the same thing in Iraq. He began his collection, which includes one of Saddam’s gold-plated Kalashnikov rifles, soon after the invasion, when a high-ranking U.S. military officer called him from the U.S. base in Kuwait with news that a bust of Saddam from a giant statue in a Baghdad square was being loaded on to a C-130 transport plane. It had been smuggled out of Iraq by an American soldier and was now bound for the U.S. Central Command headquarters in Tampa, Florida. “He asked me, ‘would you clear it?'” al-Rubaie says. “I said ‘no, we want it back. It belongs to Iraq.'” The bust, which weighs about 200 pounds, was flown back to Baghdad, where it was stored in the fortified Green Zone for two years, before al-Rubaie brought it home.

After Saddam’s execution in 2006, al-Rubaie added the length of rope around the bust’s neck—a stark reminder of a night in which he says he played a key role. The hanging took place just a few blocks from al-Rubaie’s home in the Baghdad neighborhood of Khadamiyah.

Al-Rubaie says he hoped to detect some remorse from Saddam, who was handed a Koran minutes before dying, but he remained outwardly unmoved. Al-Rubaie says he still has complicated feelings about that night. “Imagine me, a doctor since 1971,” he says. “I took the Hippocratic oath to save lives.”

Not even Al-Rubaie can be sure his rope is the one used to hang Saddam that night; he says he had asked for a length of the rope to be brought to him after the event. Nevertheless, he estimates it could be worth millions. In 2015, the al-Araby al-Jadeed news site said al-Rubaie had received offers of up to $7 million for the rope.

Al-Rubaie says he has other plans in mind. “One of my missions is to establish a museum of everything from that era,” he says, adding that he believes it is necessary to preserve the history of Saddam for future generations as a lesson in how the Iraqis lived under dictatorship. “I want to keep all things relating to Saddam,” he says. “They are all over.”

In fact, during the years after the U.S. invasion, displaying Saddam—even in jest—was a risky act. One day in 2003, an enterprising Iraqi began selling Saddam dolls in full military uniform, which danced to pop music when switched on. I bought two for $20 each, before the man was warned by locals that he could be targeted by Saddam loyalists if he failed to destroy his supply. The dolls now sit in my office in Paris, along with a supply of Iraqi dinars with Saddam’s face on them.

And somewhere in Baghdad sits the oil painting I lifted from the VIP lounge on the Jordanian border in March, 2003, during the U.S. invasion. Not knowing what to do with it, I left the painting for safekeeping in the home of an Iraqi friend, who subsequently moved to the U.S. as a refugee. That painting, along with many others hidden in corners of Iraq and abroad, might be displayed publicly again in the future—if al-Rubaie manages to someday open his museum.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Introducing the 2024 TIME100 Next

- The Reinvention of J.D. Vance

- How to Survive Election Season Without Losing Your Mind

- Welcome to the Golden Age of Scams

- Did the Pandemic Break Our Brains?

- The Many Lives of Jack Antonoff

- 33 True Crime Documentaries That Shaped the Genre

- Why Gut Health Issues Are More Common in Women

Contact us at letters@time.com