I became an executive producer over 20 years ago and happily joined a small group of upper-level female TV writer/producers who would meet every few years over brunch. We’d unload stories about the unfairness we’d encountered. I’d tell my story about the time I was renegotiating to stay on a show and the executive producer stopped by my office to check on the deal.

“Did your agents call business affairs?” he asked.

“Yep, they’re on it.”

“And you don’t care about money, right?”

I looked at my boss, incredulous. “Yeah, I’m just here for the salty snacks,” I said.

My favorite stories are ones where the sexism is blatant. As Co-EP on a show, I was asked to rewrite the script of a low-level writer. I did a big pass over the weekend and then sent the new draft to the EP on Sunday night for a polish. The next morning, the EP pulled me aside.

“Great job, Nell,” he said. “But if you don’t mind, I think it’s better if I tell Mike that I did the rewrite. I don’t want him to feel emasculated.”

The women at the brunch would gasp at these anecdotes before telling their own gasp-inducing tales. And the stories would keep coming. And coming. By the time the frittata was served, the relief of realizing the bias wasn’t personal was replaced by the horror of knowing it was so pervasive.

Around 2010, I finally started hearing some positive news about late night staffing. Jay Leno added a female writer to The Tonight Show staff and Late Show with David Letterman added one, too. And although there’d been hundreds of dads writing comedy for late night, I believe Laurie Kilmartin holds the distinction of being the first mom when she joined Conan’s staff in 2010.

Over the years, I’ve seen how women advocating for other women in late night can make a difference. When Jimmy Kimmel Live! moved from 12:30 a.m. to 11:30 p.m., ABC Entertainment President Anne Sweeney took an interest in adding more women to the staff. Head writer Molly McNearney, the only female writer on Kimmel at the time, reached out to me to get names of women who might want to submit packets. I compiled a list and encouraged Bess Kalb, a sly and hilarious writer at Wired magazine, to give it a shot. Dozens of other funny women applied. Standup Nikki Glaser was on my list but passed to focus on her performance career. The night before submissions were due, Nikki emailed me.

Nell,

I mentioned to a writer friend of mine last week that I was considering getting a packet together for you guy [sic]. She said that she was going to try to put something together as well have some manager who is hip-pocketing her submit her. Now that guy is playing dumb and saying he can’t get it to the right people.

I know it wasn’t my place to spread the word about this – and that wasn’t my intention in this case – but she just emailed to ask if I could help in any way. She worked really hard on it and I think she’s a very talented wrier. So I’m including it in this email and of course you can do what you like with it, but I just wanted to at least do my best as her friend to get it to the right people.

Thank you and I’m truly sorry if this breached any confidentiality!

Nikki

If women who don’t help women get a special circle in hell, I think women who do help women should get a special cloud in heaven. Thanks to Nikki, Joelle Boucai’s packet made it to the show. And thanks to Anne and Molly, both Joelle and Bess were hired and have worked at Jimmy Kimmel Live! for more than five years.

In 2013, Laurie Kilmartin suggested I check out the Twitter feed of Jill Twiss, who made quirky observations like, “I’m just going to say it. Bananas are cliquey” and “Pretty worried for gluten-free pigeons.” I messaged Jill to learn more about her. During the day, she tutored kids for standardized tests and moonlit as a standup comedian and actress. When Last Week Tonight began staffing up, Tim Carvell asked for names and I mentioned Jill. That show reads submissions “blind,” removing any identifying details about the writer. Out of about a hundred submissions, Jill was one of eight people hired. She now has more Emmys than I do. (Although to be fair, anyone with a single Emmy has more Emmys than I do.) Unfortunately, my system for tracking down funny female writers isn’t methodical. It’s mainly based on word-of-mouth, which can cast a limited net. I always wish that I could help more women, and especially women of color.

In an ideal world, awareness would lead to action, which would lead to change. But in the real world, awareness more often leads to defensiveness, which leads to excuses. Emboldened by the forward motion in late night, I called a showrunner who ran a popular sitcom with a huge staff and only one female writer. We knew each other socially so I thought he’d be open to a discussion. I got as far as my observation that his staff had a gender imbalance before hitting a nerve.

“How dare you accuse me of being sexist,” he said. “My mother was the breadwinner in our family and my wife is one of the strongest women on the planet.”

I tried to salvage the phone call. “I didn’t call you sexist. But just look at the numbers on your staff—”

“You think I don’t notice?” he said, ire rising. “I look around the room and notice it every . . . single . . . day.”

This showrunner bringing up his breadwinner mother and strong wife is a perfect example of “moral licensing.” Everyone — male and female — is biased. But no one wants to admit it, so our brains search for examples that disprove the accusation.

Moral licensing comes into play when people rely on past behavior to dismiss current prejudiced behavior. This is better known as the “Some of my best friends are . . .” defense. People who believe they are unbiased turn out to be more biased so it’s not enough to be aware that there’s a lack of women in a room; you must also be aware that your knee-jerk defensiveness is part of the problem.

“When you’re used to privilege,” the saying goes, “equality feels like oppression.” My showrunner friend felt under attack and our call ended on a sour note. I was angry with myself for coming on too strong. On the plus side, it taught me what not to do. It would be so helpful if blurting out, “Obviously, there’s a problem so just fix it!” worked. It doesn’t. Ask anyone fighting climate change or gun violence.

People insist the lack of women and people of color in Hollywood is “a pipeline problem.” Instead, I think it’s “a broken doorbell” problem. Competent and talented women are right there on the doorstep, leaning on the buzzer, but no one is answering the door. This fault lies in our culture’s misperceptions. Studies show that employers routinely perceive men as more competent leaders than women even when the data doesn’t support the claim. For example, software code written by women is routinely rated as higher quality by male engineers — unless the raters know who wrote it. Once gender is identified, the raters devalue the female-generated work. Men applying for jobs also benefit from being able to openly acknowledge their success. Too often women are taught to downplay their success with statements like, “I got lucky,” or, “I had help.” Guess what? The men got lucky and had help, too.

The numbers for female writers in the top late-night shows were just under 20% as recently as 2016, and mothers — who represent a truly essential point of view — remain in short supply. Some in the business still view being maternal as the antithesis of funny, since moms are associated with nurturing, gentleness and safety, while comedy wants to be twisted, dangerous and mean. But attitudes are evolving. I cheered in 2009 when a very-pregnant Amy Poehler rapped a boisterous tribute to Sarah Palin on Weekend Update. Ali Wong filmed her 2016 standup special Baby Cobra while seven months pregnant. Samantha Bee did stellar work as a correspondent for The Daily Show while pregnant and, in a New York magazine interview, urged others to try. “It’ll add to your comedy in ways that you never expected,” Bee said.

All these women are both hilarious and tough — or what I call, “maternal.”

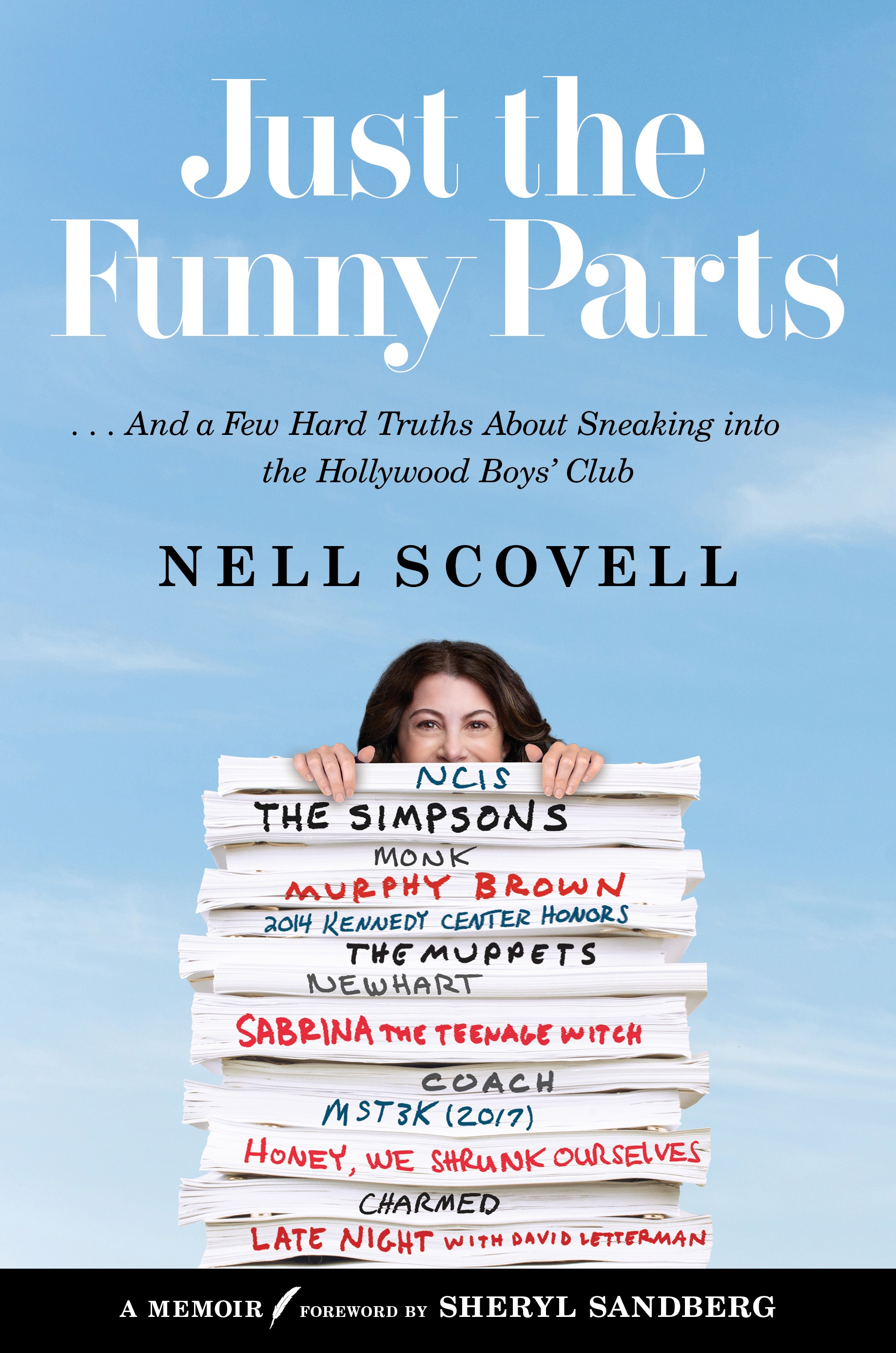

Excerpted from JUST THE FUNNY PARTS:…And a Few Hard Truths About Sneaking into the Hollywood Boys’ Club by Nell Scovell. Copyright© 2018 by Nell Scovell. Reprinted by permission of Dey Street Books, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Biden Dropped Out

- Ukraine’s Plan to Survive Trump

- The Rise of a New Kind of Parenting Guru

- The Chaos and Commotion of the RNC in Photos

- Why We All Have a Stake in Twisters’ Success

- 8 Eating Habits That Actually Improve Your Sleep

- Welcome to the Noah Lyles Olympics

- Get Our Paris Olympics Newsletter in Your Inbox

Contact us at letters@time.com