The Lara Croft digging up treasure in the new Tomb Raider film may surprise those who aren’t familiar with video games. Played by ballerina-turned-Oscar-winner Alicia Vikander, the rebooted character bears little resemblance — in her physicality or emotional makeup — to the version portrayed by Angelina Jolie in the early 2000s films. She is more muscular than buxom. She wears cargo pants instead of spandex shorts. She’s naïve and determined instead of hardened and blithe. And she’s too busy raiding an island’s worth of tombs to bother with romance.

“We wanted to make her more relatable, which we maybe leaned into a little more than the Angelina Jolie movies of the past,” says screenwriter Geneva Robertson-Dworet. “She’s tough on the outside but in a bit over her head. We wanted to give her an internal journey, not just an outward adventure.”

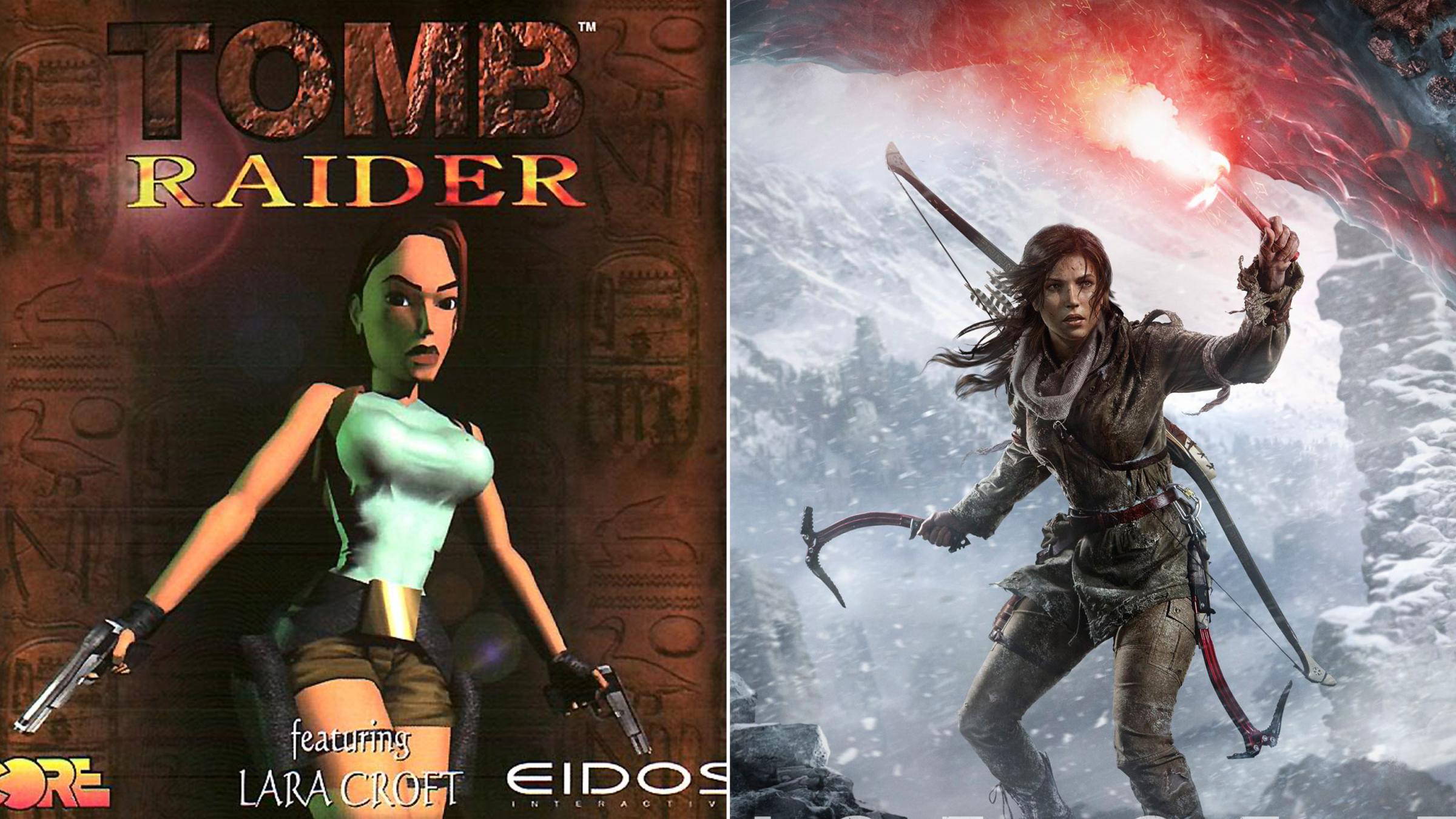

The new Tomb Raider movie — largely based on the 2013 rebooted video game series — also attempts to contend with the complicated history of the video game character. First introduced in 1996, she became one of video game’s most popular characters, simultaneously a feminist icon and sexist stereotype. Female gamers clung to her as one of the few playable female characters in video games, aside from Ms. Pac-Man. Yet the original Lara Croft character was created in 1996 by men in with men in mind, the original cyberbabe.

When gamers play as a character, they see things from their perspective. Lara Croft remains one of the few popular female video game characters that players can actually control, so how men feel when they step into Lara’s combat boots matters. “For men to say ‘I did this’ about a female avatar is a big deal in a society that teaches men not to value women’s experiences,” says Jessica Hammer, a Carnegie Melon professor who researches gender in gaming.

Lara Croft has had to carry the burden of representing the perspective of all women. “Her superpower is that she’s smart. At the same time, she’s conventionally sexy,” says Hammer. “So she becomes a flashpoint for people to talk about gender in games and gender in society.” That means Robertson-Dworet had to contend with more than just telling a good story when bringing Lara to the big screen: it also mattered how both men and women experienced this unique heroine.

The first Tomb Raider game was released just two months after the Spice Girls dropped their first single, “Wannabe.” Like her fellow Brits, Lara Croft earned fans for both her independent spirit and her sexy outfits. But unlike the Spice Girls, she was designed for a primarily male audience. In fact, her creators have admitted they were surprised when women wanted to buy the game, too.

Not only did Lara’s creators endow her with a Barbie doll figure, but the mechanics of the game encouraged objectification — already a problem in the male-dominated gaming space. The camera often focused on her rear end. (As cultural critic Anita Sarkeesian once pointed out, game makers usually cover male avatars with capes or make it impossible for the camera to zoom in on their behinds.) A rumor spread that a certain line of coding could remove Lara’s clothes. An ad campaign for the games suggested men were abandoning strip clubs to play the game and fantasize about Lara. In 1997’s Lara Croft 2, Lara climbs into a shower before turning toward the player and saying, “Don’t you think you’ve seen enough?”

Lara is far from the only sexy female avatar in video games: female heroes as well as damsels are first and foremost sexy, often fighting in heels and lingerie instead of flats and armor. “Sexiness is often used in gaming as an excuse for men to play and enjoy playing a female character,” says Hammer. “On the one hand, it gives these men a socially acceptable way to identify with a woman. On the other hand, it reinforces this notion that only women who are sexually attractive are valuable.”

By the time Angelina Jolie took on the role of Lara in two Tomb Raider films in 2001, the girl power moment had largely faded from popular culture. Jolie wore the same tight shorts sported by Lara in the game, a padded bra and even ventured into a frozen tundra in a spandex outfit. But she also exuded an untouchable cool that felt aspirational, if not relatable, to female audience members. The Croft character launched Jolie’s career as a bona fide action star at a time when few women got to star in more than one action franchise: After Tomb Raider came a sequel, Mr. and Mrs. Smith, Wanted and Salt.

Still, the Lara Croft character remained better known for her figure than for her adventures, one of the few fictional characters to be featured in Playboy magazine. After the Jolie films, video game sales slumped. So in 2013 SqaureEnix rewrote the Lara story. They changed Lara’s physical appearance, aged her down and added new depth to the character. Lara had long been infallible. The new version was cocky but vulnerable and had plenty to learn about slinging arrows and scaling mountains. Though some gamers whined about the alterations, the changes actually boosted sales. Tomb Raider (2013) became the best-selling game of the Lara Croft franchise. Together, the reboot and sequel Rise of the Tomb Raider (2016) have sold an impressive 18 million copies.

That’s not to say that SquareEnix became the model of woke gaming. The 2013 game seemed to take sadistic pleasure in Lara’s injuries and moans of pain. And before the reboot’s release in 2013, one of the creators said there would be an attempted rape scene. SquareEnix quickly walked back the language, but the actual scene remains an uncomfortable play-through: A kidnapper touches Lara’s cheek inappropriately and then chases her as she tries to escape. Make a misstep as a player, and Lara is choked to death. The scene communicates the very real threat of rape and gender violence. If Lara escapes, she learns to craft fire arrows and returns to kill the kidnappers with righteous fury. But gamers still debate whether playing through a triggering scene was worth it for the moment of empowerment.

Perhaps wisely, the creators of the new Tomb Raider film omitted this scene from the movie. They also gave Lara more of a background story: She can shoot arrows because she was once a champion archer; she can fight because she’s trained in a boxing ring; she can sprint because she’s spent months as a bike messenger.

The writer and director also decided not to give Lara a love interest. (Daniel Craig played Jolie’s in the original films.) In fact, every time any man tries to work up the courage to ask Lara out in the movie, she’s already biking away on to another adventure. “The temptation in a lot of these movies is to have a full-blown romance plot,” says Robertson-Dworet. “We wanted to explore other parts of her character.”

Small script decisions like this have begun to upend years of sexist tropes in popular culture. And the way action movies depict their heroines is beginning to change as more women have the opportunity to write empowered, realistic women: Robertson-Dworet is currently working on several other female action films, including Marvel’s first female-led superhero movie, Captain Marvel, and a Black Cat and Silver Sable film.

Gaming is beginning to change too. As video games have evolved into narrative endeavors, creators have imbued characters with new depth. At the same time, they have begun to invest in more female characters with real flaws and more clothing. Aloy, the futuristic female hunter at the center of last year’s Horizon Zero Dawn is ferocious and complex. Better yet, she’s not sexualized at all. In the much-hyped sequel to the critically-acclaimed game Last of Us, players will play not as Joel, the man who shepherded teenage Ellie across a zombie apocalypse in the original game, but as an older Ellie, a queer character who is primarily a haunted survivor, not the object of fantasy. Sports games like FIFA have recently begun featuring women’s teams alongside the men’s.

Still, there are few female characters of color or older female characters in video games. And every time a new female character crops up, some gamers bemoan the fact that there are any un-sexualized female characters in gaming at all on Reddit threads or in YouTube videos. “We could have had a #metoo moment in gaming. Instead we got #GamerGate,” says Hammer, referencing the sexist movement in the video game industry to harass female gamers and female critics. “We still have a long way to go.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Eliana Dockterman at eliana.dockterman@time.com