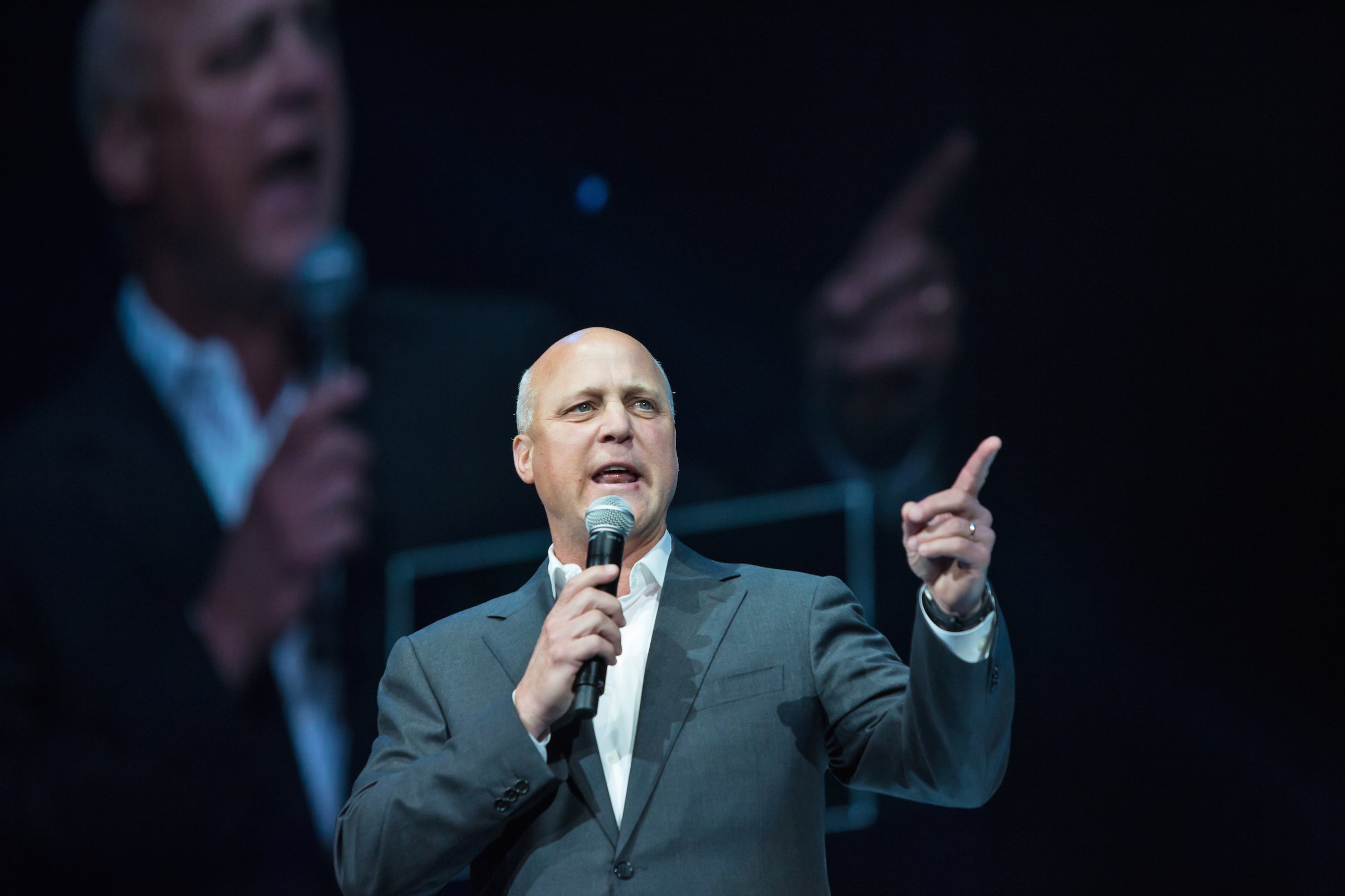

Mitch Landrieu was a child when he learned that race could be a problem in New Orleans. As the son of Mayor Moon Landrieu, who worked to integrate city government in the 1970s, he saw how deeply etched the lines of color could be. But it would take decades for the younger Landrieu to realize that the true impact of racism was deeper than he had previously imagined. In his new book, he describes one of the city’s monuments to a Confederate leader as being “there-but-not-there” in his youth; later, he would realize that many of his neighbors not only noticed the statue, but were haunted by it. In the intervening years, he became a state legislator, Lieutenant Governor and then, as the first white person to hold that job since his father had, the Mayor of New Orleans.

On May 19 of last year, Landrieu delivered a speech explaining his decision to remove four Confederate monuments from the city. His words quickly gained viral status. That topic provides the framework for the book, In the Shadow of Statues: A White Southerner Confronts History, out March 20. Part memoir and part manifesto, the book follows Landrieu’s political path as well as the evolution of his thoughts on race and history. Landrieu spoke to TIME about why the wounds of the Civil War and slavery remain unhealed, and what he thinks Americans need to do to address that problem.

You trace a lot of the problem with the statues specifically, and race in America in general, to the idea that many Americans were taught incorrect information about the past. Tell me the short-story version of the history of the Civil War as you learned it in school growing up.

It was a war between the states, fighting for all that was great about the South, that had more to do with the economy than it had to do with anything else. That was basically the story we learned.

What are kids in New Orleans schools today taught about the Civil War?

I think they’re getting a much more robust version of it. This debate about the monuments has piqued everybody’s interest in going back and looking at what’s actually in the textbooks and what is being taught. One of the reasons why I wanted to give the speech is because I wanted to, at least from a Southerner’s perspective, speak very clearly about the verdict that history has now rendered. It’s clear and it’s unequivocal. The war was fought to protect slavery, as a consequence of destroying the union. And not everybody in the South was in favor of the confederacy. I think that’s pretty clear too. It just needed to be stated.

It just seems to me that we’re far away from [the Civil War and slavery] now, where we could take a mature view of our past and try to have reconciliation in a thoughtful way, but it really can’t be done if we’re not going to tell the truth about our history. My mama, for example, said to me, ‘That’s just what I was taught. How was I supposed to know anything different?’ She was a passive recipient of bad information. You have to believe that people have the capacity, if they learn more and they know better, to grow into a different space than they have been in. Most of this stuff is taught. And if it was taught one way, it can be unlearned and taught another way.

I read in the Washington Post recently that a survey found a growing partisan divide in feelings about the teaching of black history — that about two-third of Democrats thought schools should be teaching more black history, compared with just 10% of Republicans. What do you read into that?

First of all, polls really depend on the question that’s asked. If you ask the question ‘Do you think we should teach all of our history and not just some of it?’ I bet you 95% of the people say yes. It’s important for all of us to know where we came from and how we got here. For example, if you ate a great bowl of gumbo you would want to know what the ingredients are. If somebody said, well, it’s just a certain kind of meat or it’s a certain kind of roux, and they leave out half the ingredients, it’s not going to come out as well. This is really curious to those of us who live in multicultural environments, why anybody would ignore any ingredient to any final product, whether it’s an educational product, a historical product, a food. That’s what makes us rich, that’s what makes us better, that’s what leads us to the notion that diversity is actually a strength for us rather than a weakness.

Readers may be surprised to be reminded that your battle over the monuments started not after the Charleston church shooting but earlier, when you began planning for the city’s tricentennial and Wynton Marsalis suggested you remove them. How do think that timeline affects the story, if at all?

It was important to me to make sure that the people of the country knew that some of us have been trying to work through the issue of racial reconciliation for a long time. This is not a new thing nor is it a reaction to anything that happened anywhere else. What happened with Dylann Roof, what happened in Charlottesville, what happened in other areas is symptomatic of a much larger problem that evidently the entire country is still going through.

Read an excerpt from In the Shadow of Statues here on TIME.com

Do you see the problem of reckoning with slavery as a Southern issue?

Look, I am a proud Southerner. I love the South. There are so many wonderful things about this part of the country, and as a Southerner I do feel the sting of judgment from the rest of the country that has historically been leveled against the South, as though we’re not as well educated or not as sophisticated, that somehow our commitment to faith, family and country is kind of a weird thing. That’s been an undercurrent forever. As a proud Southerner I would say that as I’ve traveled the country, that racism and prejudice is not relegated just to the South and that all of us in the country can do better over time.

You write about how you’ve been thinking about how we reckon with the past since you visited Auschwitz when you were in college, and you saw how starkly that history was acknowledged. Do you have a theory about what makes one nation confront its past head-on and another nation avoid doing so?

I do not have a theory about it but I do have an observation that I think is historically correct. It’s very hard to compare tragedies. So, apartheid in South Africa was awful and cannot be compared in any way to the deaths of six million Jews and other individuals in and around Auschwitz, nor to slavery. All three of them were catastrophically bad manifestations of human nature run afoul, and they’re all awful. I think it is fair to observe that the people of Germany and the people of South Africa have done a more constructive job of recognizing the evil for what it was, recognizing that they never wanted to repeat it and taking steps toward reconciliation. We have not done that as a country. One of the things that I was very interested in — as a legislator, as Lieutenant Governor, just a citizen of the South — is starting that discussion of reconciliation. I’ve always said that you can’t go over it, you can’t go under it, you have to go through it.

The most important six words are “I am sorry” and “I forgive you.” It’s hard to get to the next thing — and the next thing is how we unify ourselves as a country — unless and until we can recognize and confront that what was done was wrong. Some people feel assaulted by that, [as if people are saying] ‘What was done that was wrong was something you did and it was your fault.’ I mean, it can’t be anybody’s fault that exists today. You don’t have to receive the blame. I do think that you have to accept the responsibility, all of us, of fixing it — but you can’t do that until you recognize that what happened back then was just wrong. And in order to do that you have to know what the truth is, what it is that occurred.

What do you think about reparations?

Well, you know, Ta-Nehisi Coates is the one who raised that issue recently. The idea of reparations is a volatile idea. People hear that and go, Oh my gosh, why am I having to pay for something that somebody else might have done? I don’t really foresee, politically, the United States government writing a check. But there is an argument to be made, and it was made by the Kerner Commission in the ’60s and it’s been made throughout time, that one of the ways that we can begin to reconcile is to make sure that we break down the institutional barriers that have been created over time. If what they mean by reparations is recognition that we did something wrong, fixing the institutions that were broken, investing in them so that we can actually create opportunities for jobs and health care and education and generational wealth, then I don’t know that there are that many people that would disagree that that’s probably a good pathway for the country to take.

You’ve just recently announced the process for replacing the Robert E. Lee monument, which includes asking citizens what an appropriate monument to New Orleans would be. Do you have an idea of your own about how to answer that question?

I had a lot of ideas about it. It’s an opportunity for a beautiful public piece of art that not only reflects our history but also the future, and it would be wonderful if we could raise the money and get a world-class designer, maybe somebody from New Orleans, to put something there that speaks to what the essence and the soul of New Orleans really is, in totality. The problem with the Lee monument is that, besides the fact that that monument was offensive to African-Americans and didn’t really tell the whole truth, that monument in that space did not really reflect anything about the true soul and authenticity and richness of our history in New Orleans, and it’s just a bad idea to waste the most prominent space in the city. I’m obviously not going to have enough time to do that [before my term as mayor ends], and that’s okay. It’s really okay to take time with these things. Two years is a nanosecond in a 300-year history, so it’s okay. It’s also okay to leave [the space] with nothing there so people can imagine.

You write a lot about parallels between battles your father fought when he was mayor and some of those you fought. Obviously a lot has changed between then and now, but much hasn’t. Do you have strategies to avoid frustration over that?

John Lewis speaks to this issue more powerfully than any of us, and of course he’s one of my heroes. When people bemoan the fact that we haven’t made much progress, he reminds us how far we actually have come. The only way to deal with it is to continue to deal with it forthrightly and give ourselves opportunities to get better. My father reminds me that when he was a young lawyer in 1960, some years after Brown v. Board of Education had been handed down by the Supreme Court, that the language in the opinion says “with all deliberate speed,” and as a young lawyer he was sure that that meant four or five years and it was going to be over. And he now looks back at that and says, you know, “with all deliberate speed” has now lasted a long, long time and is not yet where we want it to be. Which just goes to the issue of having to keep your shoulder to the wheel. People can make a good argument that after President Obama stepped down from office, that for the last two years we’ve actually taken a step backward on the issue of race. I would have to agree in a narrow sense that that is true. That is why I spoke forcefully in the book about how, whether you’re a conservative or a liberal, whether you’re white or black, whether you believe in free markets or whether you believe in whatever, that the one thing we all have to agree on is that we cannot become a white nationalist, white supremacist nation.

How do you think being more progressive, and from a progressive political family, in a generally conservative state affects your view of things?

I don’t know the answer to that question. You kind of don’t think about it like that, you just live. When you’re living your life and just being who you’re going to be, you’re not really thinking about it from a policy point of view. I tried to explain my personal experience as a young boy growing up with a lot of African-American friends who were just like my brothers and sisters and the weird juxtaposition between what I saw and what I experienced with them, and then when I was with white people either personally or politically and I heard them say things about black people that were wrong. I just want to attest to that, which is why I say so strongly and so forcefully that I know this like I know my name is Mitchell. That our diversity is a strength, it is not a weakness. That we are a mosaic. That what we ought to be doing is asking people to teach us about the differences that they have from us, because we learn from it and we’re better for it. Not because it’s challenging to us or it’s going to take our jobs or make us less. It’s going to make us more, it’s going to make us better, and from my reflection that’s a much more American spirit than this notion that we were great once when we were white and there was some kind of mythical community that we lived in. That’s not true. That’s never been true. It’s just a falsehood. And if you try to go back and recreate something that never was, you will never, ever create a future that works for us. You just won’t. That’s not a theory or a philosophy, it’s just a fact.

You only have about two months left in office. What’s next for you? Are you running for something else?

I don’t have any plans to do anything in the future, at the moment. I haven’t really thought much about it. I’ve got to land this plane. I’m focused on that, and then I will start thinking about what if anything I’m going to do next. I don’t have any intentions to run for anything.

I saved the hardest question for last. You considered a career on the stage before you went into politics — do you have a favorite show tune?

Oh my God, yeah. “Bring Him Home” from Les Mis. I have my degree in American musical theater so I have a lot of really good ones, but that’s my favorite.

This interview has been edited and condensed.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How Donald Trump Won

- The Best Inventions of 2024

- Why Sleep Is the Key to Living Longer

- Robert Zemeckis Just Wants to Move You

- How to Break 8 Toxic Communication Habits

- Nicola Coughlan Bet on Herself—And Won

- Why Vinegar Is So Good for You

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Write to Lily Rothman at lily.rothman@time.com