Sisterhood is powerful: That’s a fortune-cookie-venerable now. Like chicken soup and reruns of the very earliest Sex and the City episodes, we take comfort in that trope. We feminists like to think that we’re sisterly across age barriers — it’s a happy idealism. So when a crack appears, it’s fret-inducing. Or, at least, question-begging.

The other day I shared my opinion on Facebook that Aly Raisman — the gymnast, six-time Olympic medalist and heroic testifer against convicted sexual predator Larry Nassar — might have been more self-protective not to have posed nude in Sports Illustrated, even though she had feminist slogans like TRUST YOURSELF and ABUSE IS NEVER OKAY written all over her body. Young women castigated me. “Her body, her decision.” “She’s got a beautiful body!” “Stop matronizing her.” I got the message: Not only was I wrong; I was old.

I’m an older Boomer, and I remember once, at 22 (my face is reddening as I type this), being “flattered” into posing nude for a photographer who probably sold the pictures to some random porn magazine. There was no term “sexual harassment” or even the concept of exploitation, only the naivete of I must be cute if he’s asking me to do this. Much more recently, an executive who was one of the first females in a male-dominated industry in the ‘80s, told me that a room in her office building was covered with girlie mag centerfolds, a low-rent machismo that would have been tacky even ten years ago.

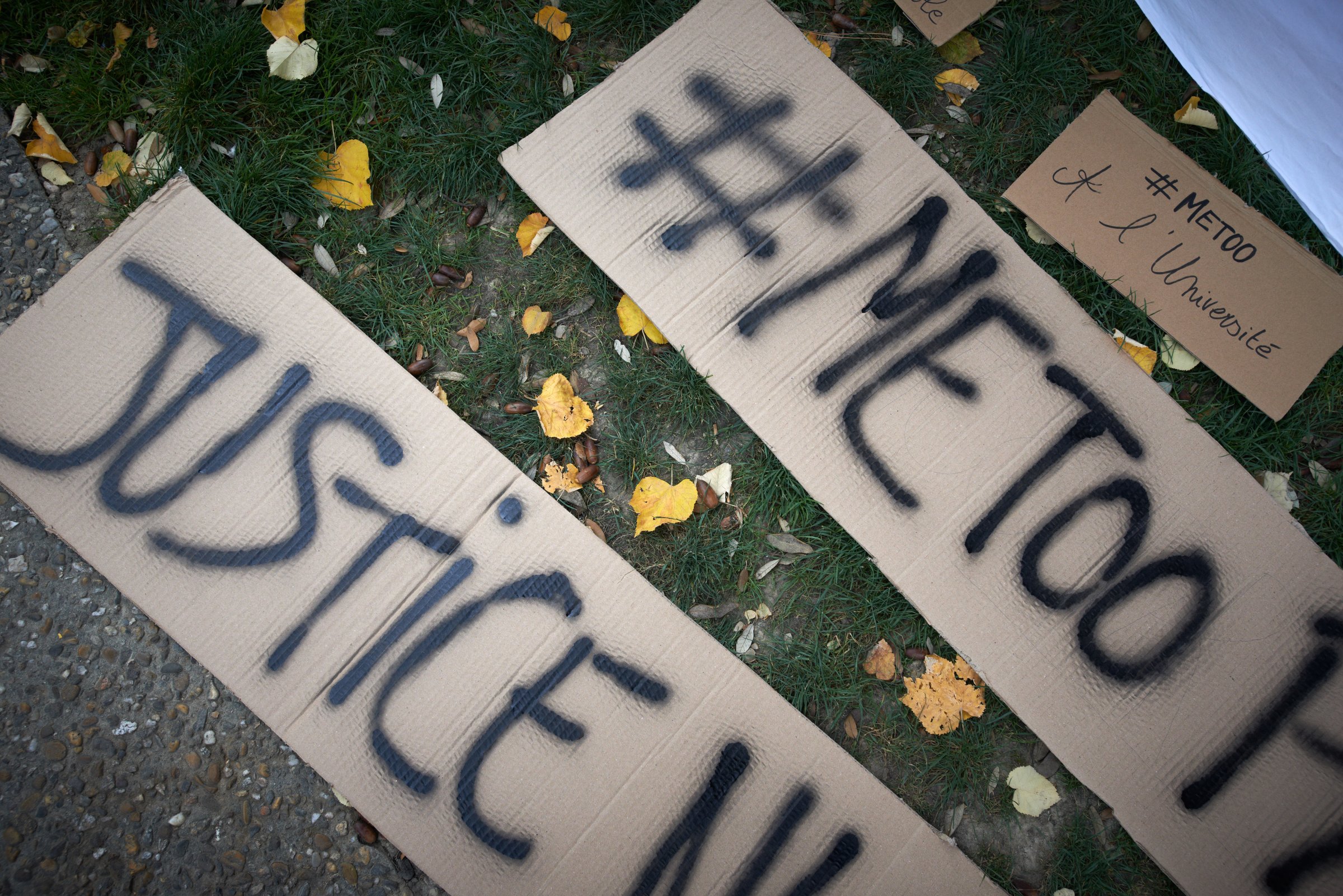

When we talk about #MeToo and sexual harassment and assault, there’s often a generational divide. Millennial women are, in their frequent own words, “zero tolerance.” Most seem to agree with the young woman, “Grace,” who compared her date with the actor Aziz Ansari to sexual assault. (Ansari has denied the accusation.) I disagreed, as did a number of other women who came to maturity before the new politics arrived with such gusto.

Communications executive Dini von Mueffling argued with her 22-year-old daughter on the Grace and Ansari incident. Von Mueffling thinks Grace had options she didn’t exercise such as telling Ansari that she didn’t want to be intimate with him and leaving. “I don’t agree that Grace’s nonverbal cues should have been enough to make Ansari stop,”von Mueffling says. But von Mueffling’s daughter is in the zero-tolerance camp, which is not uncommon.

“The women in my generation have been drawing a much harsher line for anything they consider even slightly inappropriate,” says Liz Desio, a 25-year-old executive recruiter. Desio’s mother, writer Melanie Howard says, “I feel Liz and her peers are losing the high ground and allies through their absolutism. A sloppy kiss in a bar is not the same thing as locking someone in a hotel room and forcing her to perform oral sex.”

Desio is “sad” about her mom’s generation’s belief that “a victim’s behavior” — like too much to drink — “is what in any way causes assault.” She continues, “The only problem is the action of the man. My generation grew up wanting to change our moms’ narratives.”

Similarly, women now in their 50s will remember when date and acquaintance rape was new, and paved the way for a handsome Connecticut prep kid named Alex Kelly to be convicted of raping a woman he met at a party. Until that time, “rapist” meant: a stranger who jumps out of a dark alley, period. “Acquaintance rape” convictions were progress in that power-suit, big-haired decade of the ’80s.

For older Gen-Xers, “Take Back the Night!” rallies on campuses meant: Safety and aggressiveness! We’ll get you before you get us! By 2008, the rules of that recently-enlightened game – No Means No – had flipped to Yes Means Yes, which is now the legal standard at colleges in California and New York, with many other schools across the nation embracing the policy too.

With the exception of racial politics and same-sex relationships, we’ve rarely seen social expectations and legal definitions change as full-circle as they have for sexual assault. It’s in a woman’s experiential DNA what it felt like to be young in the world of peer men, wanting to be liked and hip and fun and sexy. Millennials have done something important: They’ve made being respected and vigilant against any line-crossing as cool as being “hip and fun and sexy.” With Raisman’s feminist-statement adorned nude photo, the onus is on the leering guy, not on the proud woman. To feel otherwise, younger women believe, is to buy into creepy sexists’ low standards. I get it now.

“Our generation of women have been victims of constant name calling on social media, fat-shaming and cyber-bullying,” an 18-year old Ithaca College student named Elizabeth Adams says. I admit, this is something that my generation never had to deal with.

Adams continues, “I will not sit silent while a man accused multiple times of sexual harassment is president. #MeToo is my strong message to send.”

That’s persuasive. But I would also like young women to keep in mind what the renowned feminist Amy Richards says she knows from her years of experience, “Younger women always feel power. They think once the problem is out of the woodwork, it can be solved. Women who have been working at feminist policy for decades longer know it’s more complicated. Sexual assault rates haven’t changed in seventeen years. It takes a lot of strategy and hard work to go from different attitudes and laws to different results.”

We can be zero-tolerance, but we can’t forget Richards’ experience-based warning.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com