When I was a little girl, I used to dream as a man, because I wanted to do things that women didn’t do back then such as traveling to Africa, living with wild animals and writing books. I didn’t have any female explorers or scientists to look up to but I was inspired by Dr. Dolittle, Tarzan and Mowgli in The Jungle Book — all male characters. It was only my mother who supported my dream: “You’ll have to work hard, take advantage of opportunities and never give up,” she’d tell me. I’ve shared that message with young people around the world, and so many have thanked me, and said, “You taught me that because you did it, I can do it too.” I wish mum was around to hear the way her message to me has touched so many lives.

I remember a very funny time in my life just before I got to Africa. My paternal uncle was Sir Michael Spens, son of Lord Patrick Spens. Michael was keen to present me at court as a debutante — in those days society girls had a season of dances and balls — a kind of marriage market. Obviously to me, this was completely absurd but I had to humor Michael, and so I lined up in Buckingham Palace to shake hands with the Queen. I remember being surrounded by girls who said to me, “Don’t you dream of being a lady-in-waiting?” I replied, “Absolutely not – I want to live among wild animals.” They recoiled in horror. They thought I was very weird, but then I thought they were very weird, too.

I couldn’t afford to go to university so I got a secretarial job in London. Opportunity came with a letter from a school friend inviting me for a holiday to Kenya. (I worked as a waitress to save enough money to go.) And it was in Kenya that I met the eminent paleontologist, Dr Louis Leakey. He was impressed by my knowledge of African animals (I had read every book I could find) and sent me to observe chimpanzees in what was then Tanganyika. He felt that a knowledge of the primate most like us would help him to better understand the probable behavior of our Stone Age ancestors whose fossilized remains he was excavating. He took me despite my lack of academic credentials — or even because of them as he wanted someone with a mind uncluttered by the reductionist scientific thinking of the time.

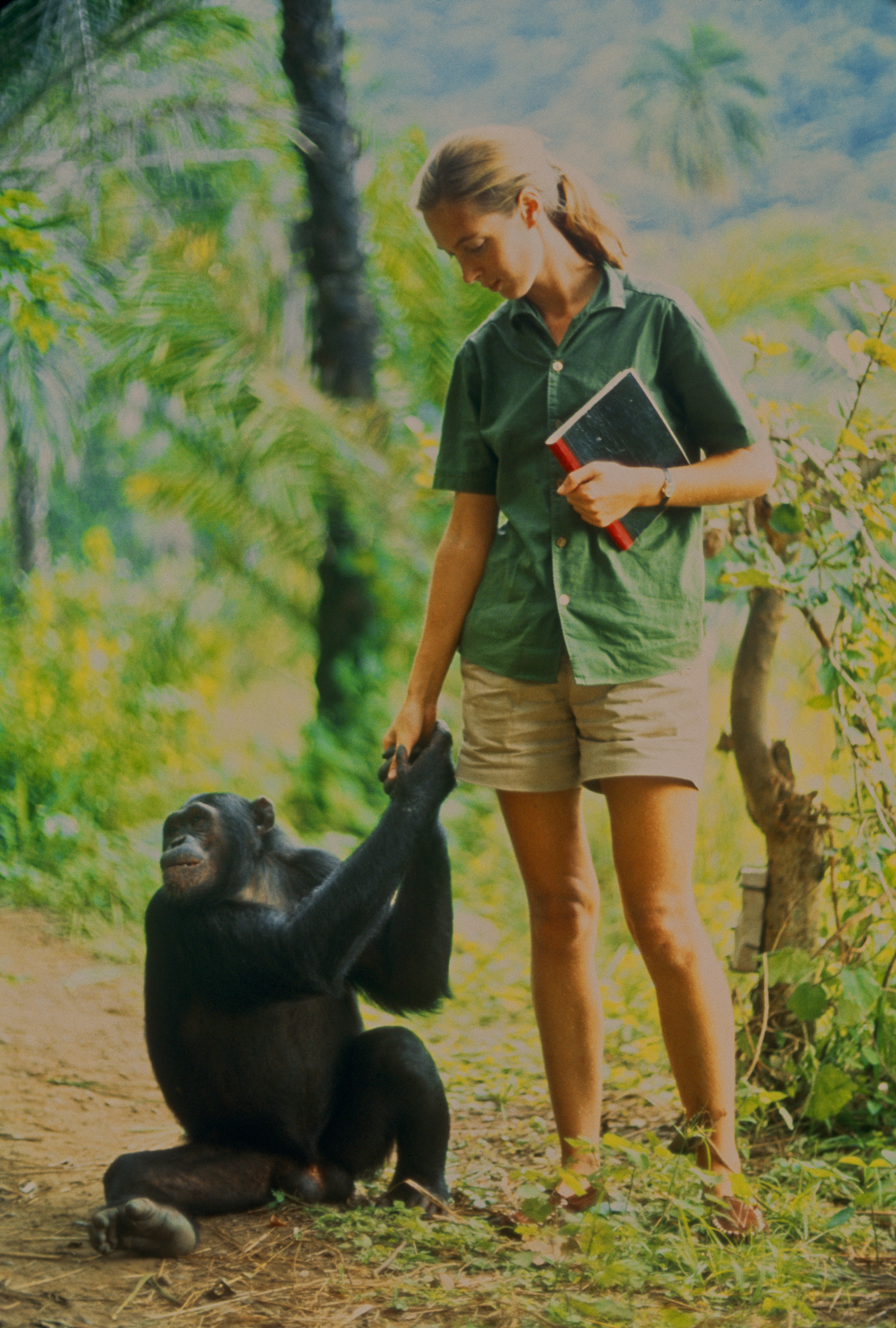

What an amazing opportunity. At first the chimpanzees ran away as soon as they saw me, but once I gained their trust I soon realized just how similar they are to us. It was an exciting day when I observed, for the first time, a chimpanzee using and making tools to “fish” termites from their nests. At that point, National Geographic offered to continue funding my research, and sent Hugo van Lawick, a talented film maker, to document the chimps’ behaviors. A year later Geographic wanted me to write an article for their magazine. And soon after that they made a documentary from Hugo’s film footage, narrated by Orson Welles.

I had to go to America, attend a press conference and give a few talks. The media produced some rather sensational articles, emphasizing my blond hair and referring to my legs. Some scientists discredited my observations because of this — but that did not bother me so long as I got the funding to return to Gombe and continue my work. I had never wanted to be a scientist anyway, as women didn’t have such careers in those days. I just wanted to be a naturalist. If my legs helped me get publicity for the chimps, that was useful.

After this Louis arranged for me to go to Cambridge University where I became the eighth person in their history to be admitted to work for a PhD without a BA. But to my dismay, I was quickly told that I had done my study all wrong. I should have numbered the chimps rather than given them names, and I could not talk about their personalities, minds or emotions as those features were unique to humans. I was told there is a difference between humans and all other animals. That way of thinking, of course, makes it easier to treat animals as things rather than sentient and sapient beings able to experience joy, fear, despair and pain. Easier to work in a factory farm or medical research laboratory and for us to enjoy the sport of trophy hunting.

But I understood the true nature of animals from my childhood teacher — my dog, Rusty. So I knew that in this respect the Cambridge professors were wrong — as does everyone who has shared their life in a meaningful way with a dog or a horse or a hamster or a bird. I stuck to my convictions and because the chimpanzees are so like us biologically as well as behaviorally, gradually scientists have become less reductionist. Indeed, animal personalities and emotions are now subjects for serious study, and there is a huge amount of research being conducted on the intelligence of animals ranging from chimpanzees, elephants and dolphins, to birds, octopuses and even some insects.

I was also told that scientists must be coldly objective and never show empathy for their “subjects.” But you can make observations that are absolutely scientifically accurate even while having empathy for the being you are studying. In fact, it can sometimes provide an intuition about the meaning of a certain behavior. You can then test your intuition with scientific rigor.

In chimp society there are good and bad mothers, and looking back over the years, we know that the offspring of mothers who were affectionate, protective but not over protective and, above all, supportive, tend to do better and to have more self-confidence. The males tend to rise to a higher position in their hierarchy and females are more successful as mothers – which is their main job. And throughout evolution this was important for the human female too – they needed to be patient, quick to understand the wants and needs of their infants before they could speak and good at keeping the peace between family members. If these qualities are, to some extent, handed down in our female genes, this may explain why women, so often, make good observers. This helped me, for Louis Leakey firmly believed that women made better field workers than men. Being a woman helped me in practical ways, too. Africa was just moving into independence and white males were still perceived as something of a threat, whereas I as a mere woman was not.

Because I succeeded in a scientific world largely dominated by men, I’ve been described as a feminist role model, but I never think of myself in that way. Although the feminist movement today is different, many women who have succeeded have done so by emphasizing their masculine characteristics. But we need feminine qualities to be both accepted and respected and in many countries this is beginning to happen. I love that the new movement involves women joining their voices together on social media, thus giving a sense of solidarity.

There are indigenous people in Latin America who have a saying that their tribe is like an eagle: one wing is male and one wing is female, and only when the wings are equally strong will their tribe fly high. And this, indeed, is worth fighting for.

JANE, premiering on National Geographic on Monday, March 12 at 8 p.m., documents how Dr. Goodall’s chimpanzee research challenged the male-dominated scientific consensus of her time and revolutionized our understanding of the natural world.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Introducing the 2024 TIME100 Next

- The Reinvention of J.D. Vance

- How to Survive Election Season Without Losing Your Mind

- Welcome to the Golden Age of Scams

- Did the Pandemic Break Our Brains?

- The Many Lives of Jack Antonoff

- 33 True Crime Documentaries That Shaped the Genre

- Why Gut Health Issues Are More Common in Women

Contact us at letters@time.com