The 10-car motorcade carrying the body of America’s most famous evangelist wound its way 130 miles through North Carolina. Down mountain roads and interstates, the cortege passed thousands of men and women who raised Bibles and American flags in tribute. Pallbearers carried the pine plywood casket into his family library in Charlotte, where former Presidents George W. Bush and Bill Clinton arrived to pay their respects. Then Billy Graham flew one last time to Washington, to lie in honor in the U.S. Capitol’s Rotunda, a recognition usually reserved for Presidents.

Graham’s final journey befitted his legend. A humble, golden-haired farm boy once felt a call from heaven, and left home to tell the world. He became one of the most charismatic figures of the 20th century, a confidant to Democratic and Republican Presidents alike. More than 215 million people over six decades flocked to hear him preach forgiveness in person. Rulers sought his counsel. He made evangelicalism relevant in the halls of power and around the world.

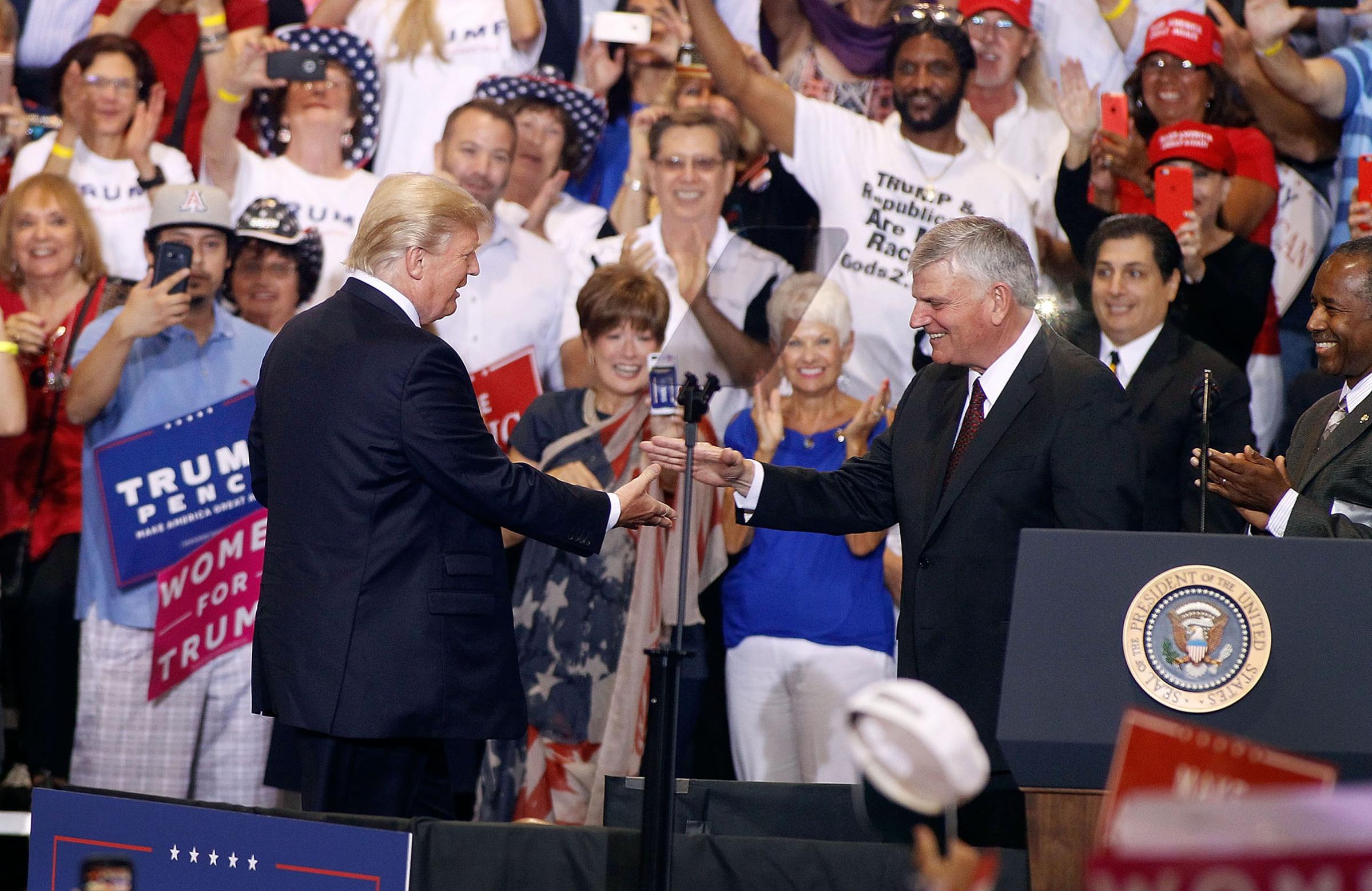

But in the wake of Graham’s death at age 99 on Feb. 21 comes discord. His prodigal firstborn son has risen as heir to his religious empire. And yet it is difficult to imagine most anything that Franklin Graham says coming from the mouth of his father. The elder Graham rose to the heights of religious power in America by uniting evangelicals after a fundamentalist crisis in the early 20th century. His son has risen to prominence by embracing the divisions of our time. He defends President Donald Trump amid allegations of affairs and hush-money payments. He rails against the Supreme Court’s ruling to legalize same-sex-marriage. He says Muslims have “hijacked Abraham,” the patriarch shared by Judaism, Christianity and Islam.

It is not just outsiders who know that the house of Graham has entered a new era of division. The difference between father and son is impossible to ignore, even for those who love Franklin most. “Daddy’s style was so gentle, maybe not in the beginning, but loving and warm,” Franklin’s sister Anne Graham Lotz told TIME in 2016. “You think of Daddy speaking at the National Cathedral after 9/11,” she said. “That is Daddy, and Franklin is just not that.” Lotz, whom Billy once called the “best preacher in the family,” has at times tried to temper Franklin’s firebrand approach but remains largely offstage as head of her own small ministry in Raleigh, N.C.

The fractured Graham legacy is about more than just the first family of American Christianity. The Grahams represent the state of evangelicalism in the U.S., pulled apart by the extremism of the day. Without their unifying senior statesman, American evangelicals today are fighting over politics, the President, Islam, women’s leadership, same-sex marriage and what the very basics of Christian witness should be. “There won’t be another Billy Graham,” says Rick Warren, pastor of Saddleback Church in Lake Forest, Calif. “The world has changed.”

Franklin, called by his father’s middle name, has long been the heir apparent to the family’s religious empire. As a young man, he was a college dropout with a taste for whiskey. When he was finally ordained at age 29, his father called the occasion “a culmination of my life’s work.” In recent years, Franklin, now 65, has run the Billy Graham Evangelistic Association (BGEA) as well as his own international Christian humanitarian organization, Samaritan’s Purse, while his father lived quietly with caretakers at his mountain home in Montreat, N.C.

Unlike his father, Franklin gravitates to the edge. During the 2016 presidential campaign, he launched a vote-your-values bus tour to all 50 states to push evangelicals to the polls. Technically, he wasn’t affiliated with the GOP, but he made his political allegiances known. In an interview with TIME on the tour, Franklin voluntarily brought up Trump more than any other Republican candidate. He called for a ban on Muslim immigration six months before Trump did and criticized people who “demonized” the police in protests over racial bias.

Franklin’s voter-mobilization efforts worked: more than 80% of white evangelicals voted for Trump. Franklin believes that God put Trump in office. He darkly declares that the U.S. has deteriorated since his father’s day, and he sees that fact as license to say what he wants. “People don’t want to be told they are sinning,” he told TIME in 2016. “I just don’t care.”

Not all of Billy’s followers respond to such rhetoric. Lotz said during the campaign that she did not think her father would have done her brother’s get-out-the-vote tour, and she raised her concerns to both Franklin and the BGEA board, on which she also serves. But like her father, Lotz is diplomatic, and she believes God is using her brother. “As my mother would say, He goes where angels fear to tread,” she said. “One of the issues we have today is that so many of the political issues are moral issues, and you have to take a stand.”

Lotz, 69, has never been her family’s public protagonist. She leads her own Christian organization, AnGeL Ministries, headquartered in an unassuming building near a Raleigh strip mall. Like Franklin, Lotz worries about abortion and same-sex marriage. But she rarely mentions culture-war issues. Even talking about evangelicals as a voting bloc concerns her. When pressed, she says she would have voted for Carly Fiorina had she survived the primaries. “Politics is not our message,” she said in 2016. “If evangelicals are all aligned with ‘this,’ then how can we reach the people over there, on the other side of the aisle, with our message?”

Lotz prefers to follow the model of a biblical prophet who wept and prayed over society’s sins instead of losing his temper and pointing fingers. But that leaves her, and those like her, wandering in the wilderness of today’s American evangelical landscape, far removed from the movement’s fiery leaders, including her brother. Her organization takes in a mere $1 million a year, a fraction of the BGEA’s annual revenue of about $100 million. Even if she had a wider cultural following, most evangelical churches do not let women preach.

![Billy Graham [& Family] Billy Graham family franklin graham](https://api.time.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/billy-graham-death-franklin-graham-presidents-family-1.jpg?quality=75&w=2400)

The difference between father, son and daughter says as much about the changing nature of the U.S. as it does about the Graham family. Both Billy and Franklin are creatures of their generations. Billy rose to greatness by giving evangelicals a vision beyond the fundamentalism that had taken hold during the evolution and creation debates and the Scopes trial of 1925. He navigated a path through the civil rights era, holding racially integrated crusades across the South but stopping short of marching with Martin Luther King Jr. in Selma. He was no saint–tapes secretly recorded by Richard Nixon revealed Billy making anti-Semitic remarks with the famously bigoted Republican President. But Graham’s light touch gave his followers a way to embrace traditional American revivalism outside of the hot political issues of the day.

The American religious landscape was changing in Billy’s final decade. More than a third of millennials identify as religiously unaffiliated, more than any previous generation, according to the Pew Research Center. Only 41% of millennials say religion is very important to them, compared with 72% of the Greatest Generation. The youngest evangelicals are increasingly diverse and more open to same-sex marriage than their elders. At the same time, and perhaps in response, their elders have dug in. Billy’s alma mater, the evangelical Wheaton College in Illinois, made national headlines in recent years not for spiritual revival but for opposition to the Affordable Care Act’s contraception mandate and for the racial tensions driven by the contentious departure of its only black tenured female professor in 2016.

Nothing has revealed evangelicalism’s divisions more than Trump’s rise. If the white evangelical base that for decades looked to Billy for inspiration began to fracture as he aged, it flat out splintered in the 2016 presidential primaries. Some of the faithful opted for more traditional representatives of the conservative social agenda, like Ted Cruz, Jeb Bush or Marco Rubio. But a large contingent of white, blue collar, non-college-educated evangelicals united around Trump. And once atop the GOP ticket, Trump attracted new fundamentalist forces into an alliance with more traditional evangelicals. Prosperity gospel and Pentecostal pastors found political power attaching themselves to a thrice-married, foulmouthed businessman.

In this environment, Franklin’s way found success. His hard-edged politics earned him the President’s ear. His Facebook following has roughly doubled since his 2016 tour, from 3.4 million to 6.5 million. His daily, often controversial posts earn tens of thousands of likes and shares, evangelizing a new, different audience from that of his father. At the same time, Billy’s passing leaves many less strident evangelicals without a leader. Lotz has chosen prayer amid the rancor. Warren hopes to find a way for evangelicalism to rebuild “credibility and trust.”

And so Billy Graham’s journey, ironically, ends amid the divisions he once healed. His burial makes that clear. Even a decade ago, when people imagined Billy’s funeral, it was a given that all living former Presidents would attend. Now, when Franklin eulogizes his father on March 2, the only Commander in Chief expected in the audience is Trump.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- TIME’s Top 10 Photos of 2024

- Why Gen Z Is Drinking Less

- The Best Movies About Cooking

- Why Is Anxiety Worse at Night?

- A Head-to-Toe Guide to Treating Dry Skin

- Why Street Cats Are Taking Over Urban Neighborhoods

- Column: Jimmy Carter’s Global Legacy Was Moral Clarity

Contact us at letters@time.com