A venerated and hugely bankable actor’s swift stigmatization following a sex scandal. An eleventh-hour casting change and directorial reworking that could earn an actor an Oscar. A fat, glaring case of workplace sexism, capped by a striking act of decency. These are the types of things that are supposed to happen in the movies, not around them.

But this is the new Hollywood. All bets are off. And so this past fall’s All the Money in the World, now an Oscar contender, underwent a near total overhaul in just a few weeks before its scheduled release in late December. The film first hit turbulence after numerous men accused star Kevin Spacey of sexual assault or harassment. All scenes featuring Spacey were then reshot with the actor Christopher Plummer–an unprecedented move that increased the film’s budget by an estimated $10 million. Then, after the film’s release, it was revealed that actor Mark Wahlberg had earned $1.5 million to reshoot his scenes, while his co-lead Michelle Williams had been paid less than $1,000. Following a public uproar, Wahlberg donated his $1.5 million to the Time’s Up Legal Defense Fund, a recently established initiative to provide legal support to those who have been sexually harassed, assaulted or abused in the workplace. Plummer has now been nominated for a Best Supporting Actor Academy Award.

This wild domino chain of events could have taken place only in the wake of Harvey Weinstein’s downfall, which sparked an unprecedented reckoning in Hollywood and changed the way we talk about sex and power in the world at large.

Although Hollywood has long been awash in liberal thinking, it’s also a place steeped in tradition and habit. And let’s hang on to some healthy cynicism: it is absolutely a place where making money takes precedence over just about everything else. Power has always been concentrated in the hands of the few–mostly, historically, men. Connections are valued over merit. Unless you count the stark, simplified good-vs.-evil moralism seen in most comic-book movies–which are among Hollywood’s biggest moneymakers–or the big end-of-year prestige pictures trotted out in hopes of winning an Oscar, Hollywood as a business entity doesn’t give much of a damn if a movie sends out a “positive” message or not.

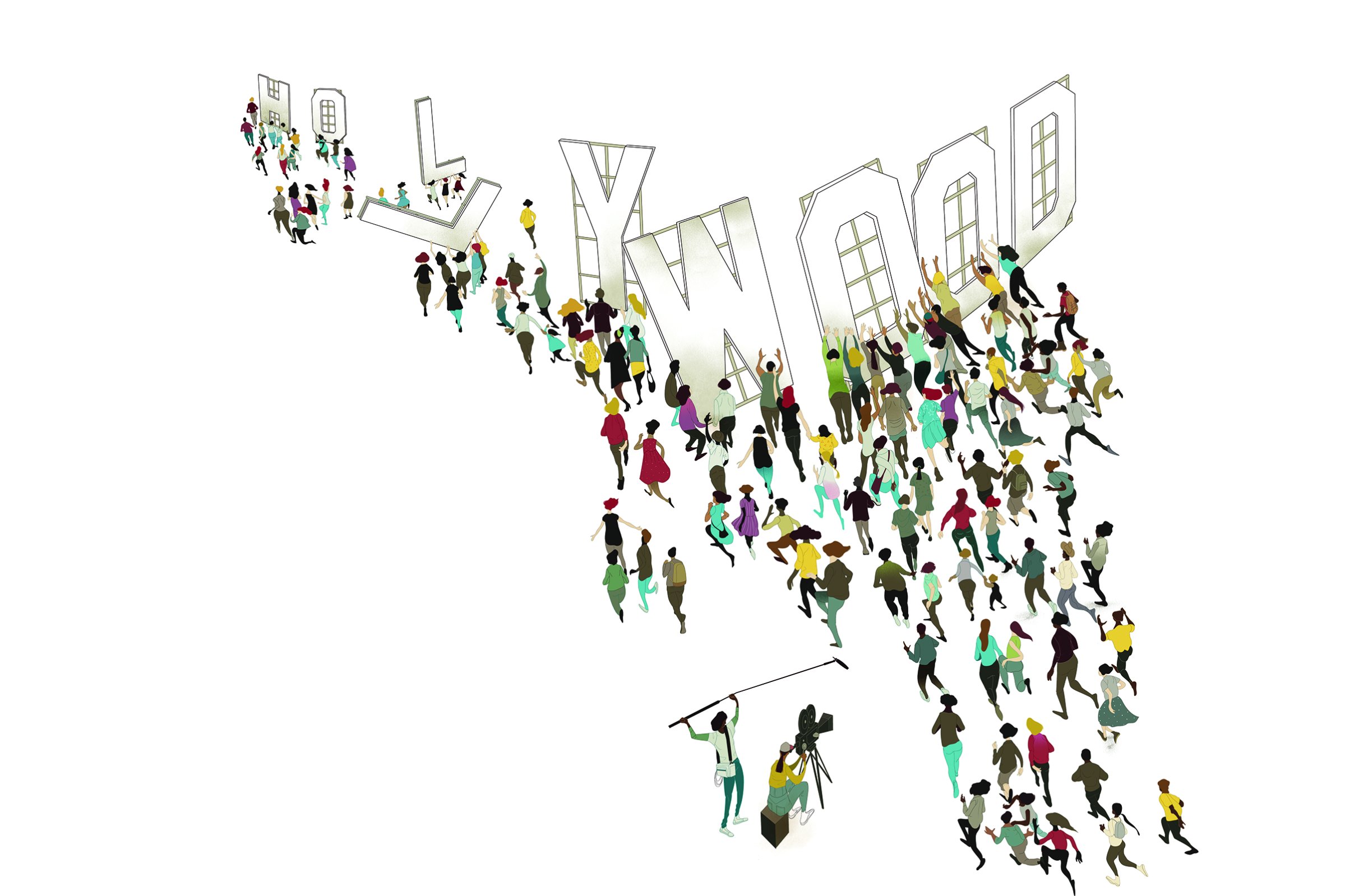

But if America overall seems to have backslid into a darker age, Hollywood is examining everything in a new, more starkly revealing light. Over the past five months alone, Hollywood has moved quickly to right long-established wrongs and to rattle ancient modes of thinking. The revelations about Weinstein crashed like a tidal wave: even though the fallen mogul had plenty of enablers, relatively few people–beyond the women he abused or harassed–grasped the full extent of his manipulative, devious behavior. In our naiveté, we’d always assumed that beautiful, successful female actors just drifted through life, untouched by the travails ordinary women deal with every day; suddenly, we knew differently, as women risked their careers to speak out first about Weinstein and then, in a swell that became bigger and louder by the day, other abusers. The subsequent and swift downfall of other Hollywood players changed everything about how we view women–or anyone who doesn’t hold the big power cards–in the entertainment business. Now Hollywood isn’t just part of the political conversation; it’s actively driving it, motivating its denizens to speak out about certain core American values in a way we’ve never seen before.

What does it mean to be an American? What color is the hat you’re wearing, and what does it say on the front? What rights do you stand up for, and which–or how many–are you willing to let pass by? Hollywood is something that defines us as Americans, for better and worse. Movies are, after all, one of our biggest cultural exports, one of our chief modes of presenting ourselves to the world. But even just watching them means something. What mark do the movies–and, to some extent, the people who make them–leave on us?

The Oscar nominations this year tell the story of Hollywood’s recent evolution. Black Lives Matter, which sprang to life after the 2013 acquittal of George Zimmerman in the killing of Trayvon Martin, not only opened new conversations about racism and the justice system, but also pushed us to think harder about representation of people of color in the movies–and about who was getting to make those movies. In 2015, you would have had to be blind not to see a problem: nearly all the Oscar nominees were white, and that wasn’t even anything new. It was simply that, finally, the world at large had taken notice.

Because movies still take a great deal of time to conceive and produce, Hollywood can’t respond to current events as quickly as the television industry often can. But in 2017, we began to see some evidence of Hollywood’s willingness to change. Jordan Peele’s Get Out–a horror movie that tangles with spiky questions about what it means to be black in a country where white people still hold most of the cards–was a huge box-office success and also earned Oscar accolades, including nominations for Best Picture, Director, Original Screenplay and Actor (for Daniel Kaluuya’s agile, alert performance). Disney/Pixar’s Coco–nominated for Best Animated Feature, as well as for its music–enchanted audiences not just because it’s set in Mexico and features Latino characters, but also because of its openness and sensitivity about death. Dee Rees’ superb multifamily historical drama Mudbound earned four nominations, including one for Rees’ and Virgil Williams’ adapted screenplay. The picture is so good, it should have gotten more. But at least the academy has recognized Mary J. Blige’s sterling, understated supporting performance as well as the song she performs for the movie (which she co-wrote with Raphael Saadiq and Taura Stinson).

Those nominations aren’t the end of change, but they are a beginning. It’s as if an egg has cracked open, and there is no putting its contents back inside. We know that we need to see and hear from more women of color, and that shift will further expand the conversation about race and gender in this country. Accordingly, this year will bring us Ava DuVernay’s eagerly awaited A Wrinkle in Time, a fantasy universe imagined for the big screen by a black woman.

And in terms of the Oscar race, specifically, it’s a year of milestones for women. With Lady Bird, Greta Gerwig becomes the first woman to be nominated in the Best Director category for her solo debut; the film received four other nominations, including one for Gerwig’s screenplay. (She is one of only five women to be nominated for Best Director since the first awards were presented in 1929. Kathryn Bigelow was the first woman to win that category, in 2010, for The Hurt Locker.) And in a field that’s perhaps even less hospitable to women than directing, Rachel Morrison has become the first female director of photography to be nominated for a Best Cinematography award, for her extraordinary work in Mudbound. It will be terrific if she wins. But even if she doesn’t, the nomination alone is a huge step forward for women working below the line in Hollywood, in terms of both visibility and pay equity. It might even inspire young women to step into the more technical fields and help create a web of support for them.

This new Hollywood, far from perfect but changing swiftly in exciting and encouraging ways, is one sign of hope that America can live up to its ideals. Right now, we have a President who communicates via a bizarre language of perpetually shape-shifting Twitter communiqués and a capital in gridlock. But Hollywood–traditionally the first place we’d turn when looking for bad behavior or salacious gossip–has in many ways come to seem more thoughtful, stable and forward-thinking than Washington. Consider a mass-market entertainment like Ryan Coogler’s Black Panther, which, though set largely in Africa, speaks of an America that’s more inclusive rather than less. A movie like Black Panther, with roles for many terrific black actors who have been underserved by mainstream projects, probably couldn’t even have gotten made just five years ago. Yet this well-crafted, thoughtful picture not only exists but also has become a massive worldwide hit. This isn’t just the kind of movie America wants to see; it’s what the world wants to see, and it helps put our best face forward as a nation. If Hollywood is going to continue to thrive as a worldwide economic force, then wouldn’t it be smart to keep telling stories that people of all races, orientations and beliefs can respond to? The best way to do that is to shift the balance of power in Hollywood.

When Oprah Winfrey, accepting the Cecil B. DeMille Award at the Golden Globes in January, made an impassioned, politically tinged speech–defending the press “as we try to navigate these complicated times” and asserting that the major changes of the future will come from women of all colors–both the press and casual viewers wondered if it was a nascent bid for the presidency in 2020. Will she or won’t she? Should she or shouldn’t she? Those questions are beside the point. The crux is that this perfectly constructed and delivered speech, an oratory feat ringing with common sense and generosity, was the kind of dignified, respectful statement that many Americans would generally hope to get from Washington–in at least some form, partisan differences notwithstanding–and which, these days, is nowhere in evidence.

Instead, our nation’s capital has made Tinseltown seem like a role model. Consider the magnitude of this change: Stars speaking out freely about sexual harassment and pay inequality. A hugely popular businesswoman, actor and television personality igniting the hope that Americans can find a way to put their most generous ideals to work. Old ways of doing business falling away, albeit slowly, to make room at the table for men and women of all colors. It would have been unimaginable in another era.

We’ve entered an age in which we can’t afford to look away, or even to blink–for better and for worse. Every choice a studio makes, in terms of its casting or choice of director for a specific movie; every report of inappropriate or outright illegal behavior by a male power player; every time it comes to light that a woman has been paid less than a man for the same work–thanks to social media, almost nothing can be hidden anymore. This new era in Hollywood is largely about self-scrutiny. Men are asking, Have I ever done–or am I currently doing–anything that could be construed as abusive or inappropriate? Men and women are asking if they’ve done all that they can to widen opportunities for people of color. Suddenly, everyone is nervous about practically everything, asking questions about what needs to change. This degree of scrutiny is a double-edged sword: while, say, having more women and people of color as filmmakers and screenwriters means that a wider range of stories will be told, the notion that every idea needs to be run through a filter to make sure it’s completely fair and inoffensive to everyone isn’t the best way to make art.

But this new era demands that we feel uncomfortable–it’s the only way to change all the things we’ve become too comfortable with–and thank God that Hollywood at least recognizes that it has reached a crossroads. Changes in Hollywood thinking have the potential to change American thinking. Decisions that get made in the coming year will affect not just the movies we see in 2019 and ’20 but also how movies get made for decades to come. Right now, at least some of the plainspokenness and human compassion that so many people in this country are wishing for and not getting in Washington is coming from Hollywood. The “new” Hollywood that today’s progressive thinkers are driving toward–a place where the voices of women and minorities are heard and valued, where white men don’t hold all the power and make all the money–is a kind of mini utopian America. That by itself is cause for optimism, and as energizing as Oprah’s Golden Globes speech was, she doesn’t have to run for President to foment change. At a point when so many people feel so hopeless about the direction we’re headed in as a country, Hollywood is striving to improve its own governance. Maybe, in leading by example, it can force a shift in America’s.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com