On July 27, 1967, President Lyndon Johnson stood before a national television audience to announce the creation of the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders (NACCD). The speech followed deadly and destructive riots in Newark and Detroit, which marked the culmination of four consecutive summers of racial unrest in American cities.

Creating a presidential commission seemed like the ideal option: it allowed him to demonstrate leadership without committing his administration to a specific course of action. He planned to kick the issue of urban violence down the road in hopes that by the time his commission issued its report, the crisis would have already passed. It was a strategy many postwar American presidents used to handle vexing political issues. Between 1945 and 1955, there was an average of one and a half presidential commissions appointed every year. Johnson would appoint twenty such commissions during his tenure as president. As the burdens on the presidency increased in postwar America, commissions became a convenient way for presidents to fill the gap between what they could deliver and what was expected of them. The popularity of presidential commissions also reflected the postwar fascination with experts and the belief that social scientists could offer objective solutions to complicated social problems.

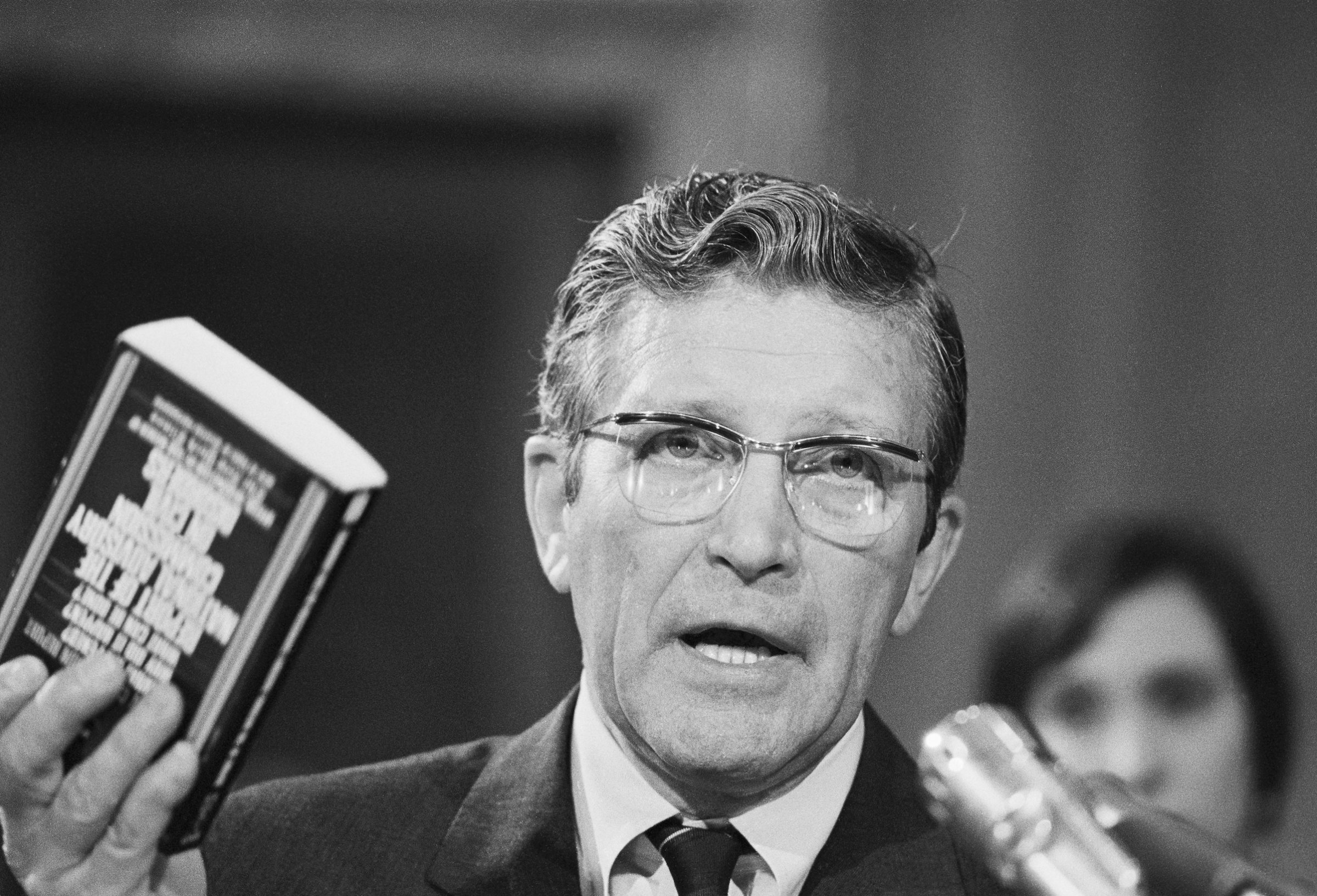

Johnson filled the eleven-member commission that he announced that evening with mainstream bipartisan figures. For chairman, he selected Illinois Democratic governor Otto Kerner. Although Kerner would not play a major role, his name would become synonymous with the commission and its work. New York’s liberal Republican mayor John Lindsay served as vice chairman. There were two African Americans, two Republican and two Democratic members of Congress, representatives from both business and labor, and one woman. There were no radicals or young people, and there was no spokesman for the black nationalist movement. Johnson assumed that his mainstream commission would produce a mainstream report that would endorse the broad outlines of his existing domestic agenda and insulate him from attacks both from the right and from the left.

The new commission, however, failed to follow the White House script. Determined to assert their independence, commissioners hired a team of investigators, visited riot-torn areas, and held hearings with activists and public officials. Their final report, released in March 1968, used stark language to conclude that the riots occurred because white society had denied opportunity to African Americans living in poor urban areas. The report offered dire warnings that only aggressive federal action could prevent future unrest. It proposed a long list of specific recommendations, including the construction of six million new housing units, greater federal spending on education, and more generous welfare payments to those in need. The report stopped short of what many activists and some liberals might have liked, though. At the same time, the cost of funding the report’s proposals was far more than President Lyndon Johnson could afford to spend while fighting a billion-dollar war in Vietnam.

Most observers focused on two lines in the summary of the report. Borrowing language from the landmark Supreme Court decision in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka (1954), which declared that “separate educational facilities are inherently unequal,” the Kerner Commission concluded, “Our nation is moving toward two societies, one black, and one white—separate and unequal.” It also placed blame for urban ills on “white racism.” The report asserted, “What white Americans have never fully understood—but what the Negro can never forget—is that white society is deeply implicated in the ghetto,” adding, “White institutions created it, white institutions maintain it, and white society condones it.”

In many ways, it was remarkable that this group of establishment figures would point an accusatory finger at white racism. Before joining the commission, most members had only an abstract awareness of the conditions in poor urban areas. They were shocked by what they witnessed in their trips to riot-ravaged neighborhoods and by the willful neglect exhibited by white officials and public institutions. They saw firsthand that African Americans attended poorly funded schools and lacked access to jobs and even to decent sanitation. At the same time, the commission’s field teams, sent to conduct intensive research in the riot cities, sent back damning reports that underscored the wretched conditions in many areas and documented a history of discrimination and white indifference to black concerns. As a result, a broad consensus emerged among the commissioners that they needed to use the report to educate the public and to do so by using provocative language that would shake white America from its indifference.

Had the report been written a few years earlier, LBJ might have embraced it and its recommendations. But the commission’s independence and ambition came at an inconvenient time for the White House. LBJ’s coalition was crumbling, the federal budget was tighter, and the president faced stiff opposition for his party’s nomination. Fearing that he had created what domestic policy adviser Joseph Califano called “a Frankenstein monster,” Johnson soured on his commission within weeks of announcing its creation and worked behind the scenes to sabotage its investigation. Privately, he had promised to fund most of the commission’s work with a December supplemental spending request to Congress. He reneged on that pledge, hoping that cutting the commission’s financial lifeline would force it out of business before it could issue a final report. But the gambit failed. In the end, a resentful and angry LBJ refused to accept a copy of the final report, and, in a fit of childish pique, he did not even sign customary letters thanking the commissioners for their service.

The tensions between the commission and the president were dramatic, but the commissioners and their staff were also deeply divided, despite the unanimous report they eventually produced. The debates on the commission exposed the fault lines that were emerging in American society. Generational and ideological differences split the young field team members, many of whom had been radicalized by their service in the Peace Corps or their time spent in the civil rights movement in the South, from the mainstream liberals, who dominated the senior positions on the commission. Deep ideological conflicts among the commissioners themselves reflected the larger public debate over race and riots. The commissioners could not agree on what caused the riots or on what solutions they should offer for preventing future violence. Largely because of John Lindsay’s efforts, the final document managed to speak with one voice and to push liberalism to its limits. At just the time that the administration was trimming its sails, the commission issued a report that held LBJ accountable for the bold goals he had set in the early days of his administration.

Although the final report was unanimous, the commissioners had failed to reach consensus on many of their specific recommendations. In fact, the commission serves as a microcosm of the unraveling of postwar American liberalism. LBJ had chosen the commissioners because they each represented a constituency that made up his broad coalition. Their work on the commission, however, pushed members in very different directions and exposed the fragile nature of LBJ’s consensus. Lindsay and Oklahoma senator Fred Harris would become increasingly skeptical that the nation could solve problems of race and poverty without fundamental changes that went beyond conventional politics. Within a few years, they would redefine themselves as nonpartisan populists, campaigning against a corrupt political system. Although he lost many of the votes on the commission, businessman Charles “Tex” Thornton’s advocacy of law and order, and his professed fears of a white backlash, anticipated the conservative revival building on the horizon of American politics.

The Kerner Report represented the last gasp of 1960s liberalism— the last full-throated declaration that the federal government should play a leading role in solving deeply embedded problems such as racism and poverty. A Democratic Congress would continue to pass progressive legislation for the next decade, but none of it came close to the ambition and scope of the Kerner Commission recommendations.

Nevertheless, the Kerner Commission’s legacy is enduring, and its haunting prediction about America becoming two societies, separate and unequal, is as relevant today as it was five decades ago.

Adapted from Separate and Unequal: The Kerner Commission and the Unraveling of American Liberalism by Steven M. Gillon. Copyright © 2018 by Steven M. Gillon. Available from Basic Books, an imprint of Perseus Books, a division of PBG Publishing, LLC, a subsidiary of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com