John McCain was a realist. At challenging moments, he often uttered a favorite quip, misattributed to Chairman Mao: “It’s always darkest before it’s totally black.” The accompanying glint in McCain’s eye captured the combination of fatalism, determination and comic relief that defined his distinctly American spirit. Few knew better than the former prisoner of war, veteran legislator and two-time presidential contender that life is cruel, the fates are fickle and the situation can always get worse. Best to call it like you see it, crack wise and forge ahead.

McCain, an Arizona Republican and steady defense hawk, died Saturday at 81. The Navy pilot survived a five-year stay at the Hanoi Hilton and several bouts of skin cancer before succumbing to an aggressive form of brain cancer, diagnosed in July 2017. On Aug. 24, the McCain family released a statement announcing the Senator would no longer be undergoing medical treatment, all but telegraphing to the country and to the world that the fight was coming to an end.

“Senator John Sidney McCain III died at 4:28pm on August 25, 2018. With the Senator when he passed were his wife Cindy and their family. At his death, he had served the United States of America faithfully for sixty years,” his office said in statement Saturday night.

Even as the darkness closed in on him, McCain continued in his role as America’s elder statesman and independent voice. One of his signature votes in a lifetime of service came shortly after the brain cancer diagnosis, when he defiantly blocked fellow Republicans’ attempts to scrap the Affordable Care Act, a final act of maverick pluck signaled in a late-night vote with a simple thumbs-down. A few weeks later, when Republicans tried to revive their repeal efforts, McCain again was a nay. Despite lobbying efforts from Lindsey Graham, McCain didn’t budge on the September reboot. His death left the GOP, and the country, without a signal voice that rose above party.

McCain was an American original and an icon. His temper was legendary, his warmth remarkable. He swore like the sailor he once was and loved a good night in a casino, occasionally staying well past midnight with friends, lobbyists and fellow lawmakers. He fought with members of both parties, shrugged off his critics and often remarked that while no one would mistake him for Miss Congeniality, no one would accuse him of being a pushover. His political instincts weren’t inerrant, but his principles rarely wavered. The slogan of his unsuccessful 2008 presidential campaign, Country First, rang true until the end.

A PRISONER IN NORTH VIETNAM

John Sidney McCain III was born Aug. 29, 1936 in the Panama Canal Zone, a prince among the Navy elite. His grandfather, known as Slew, helped the Allies win the Pacific campaign during World War II, rising from the head of air command in the South Pacific to the number-two Naval officer at the Pentagon and finally chief of staff for the Third Fleet. When the Japanese surrendered aboard the Missouri, Slew was in the front row of that famous photograph. John McCain Jr. followed in the family business, becoming the top commander for Vietnam from 1968 to 1972. Growing up in Washington, the youngest McCain, nicknamed “McNasty” by his prep school classmates for his disposition, felt the call of duty; he entered the U.S. Naval Academy in 1954.

“I remember simply recognizing my eventual enrollment at the Academy as an immutable fact of life, and accepting it without comment,” McCain wrote in 1999. What he lacked in academic performance he compensated for with demerits, earning more than 100 each year for offenses ranging from un-shined shoes to speaking out of turn to smuggling a television into the dorms. Another favorite go-to line of McCain’s was that he graduated fifth from the bottom of his class. He was not exaggerating.

Despite his poor academic transcript, McCain was commissioned an ensign and spent two years learning to fly planes, first in Florida, then in Texas. By his own account, he enjoyed the life of a bachelor, dating a stripper and driving around Pensacola in a white Corvette convertible. He was not a natural in the cockpit; in 1960 he crashed his single-seat propeller plane into Texas’ Corpus Christi Bay—the first of his four crashes, including the one that made him into one of the nation’s most prominent POWs. Navy officials questioned his judgment, but he continued to fly and became a flight instructor at an airfield named for his grandfather.

In 1965, McCain married his first wife, Carol Shepp, a model. He legally adopted two children from Shepp’s first marriage, and in 1966 the young couple had a daughter, Sidney. A year later, McCain was in the Gulf of Tonkin aboard the U.S.S. Forrestal, off the coast of Vietnam, on an assignment that drew global headlines when a munitions accident killed 134 sailors. McCain remarked days later to The New York Times that seeing the destruction brought by the bombs and napalm gave him second thoughts about dropping them on the North Vietnamese. The Forrestal was so badly damaged that the Navy considered abandoning ship.

But neither that queasiness nor misgivings about the strategies concocted by Washington bureaucrats would stop McCain from flying 23 missions over North Vietnam. His final one came on Oct. 26, 1967. As McCain was dropping bombs on his target, a power plant in central Hanoi that was typically off-limits to American planes, a surface-to-air missile the size of a telephone pole hit the right wing off his Skyhawk dive bomber. McCain, 31, crashed into Truc Bach Lake and nearly drowned. With two broken arms and a broken right leg, he used his left leg to kick to the surface and inflated his life vest through his teeth. Struggling to dry land, he was attacked by the North Vietnamese; his left shoulder was crushed and his stomach lanced by a bayonet. He was in dire condition by the time he arrived at the Hỏa Lò Prison, known to American soldiers as the Hanoi Hilton.

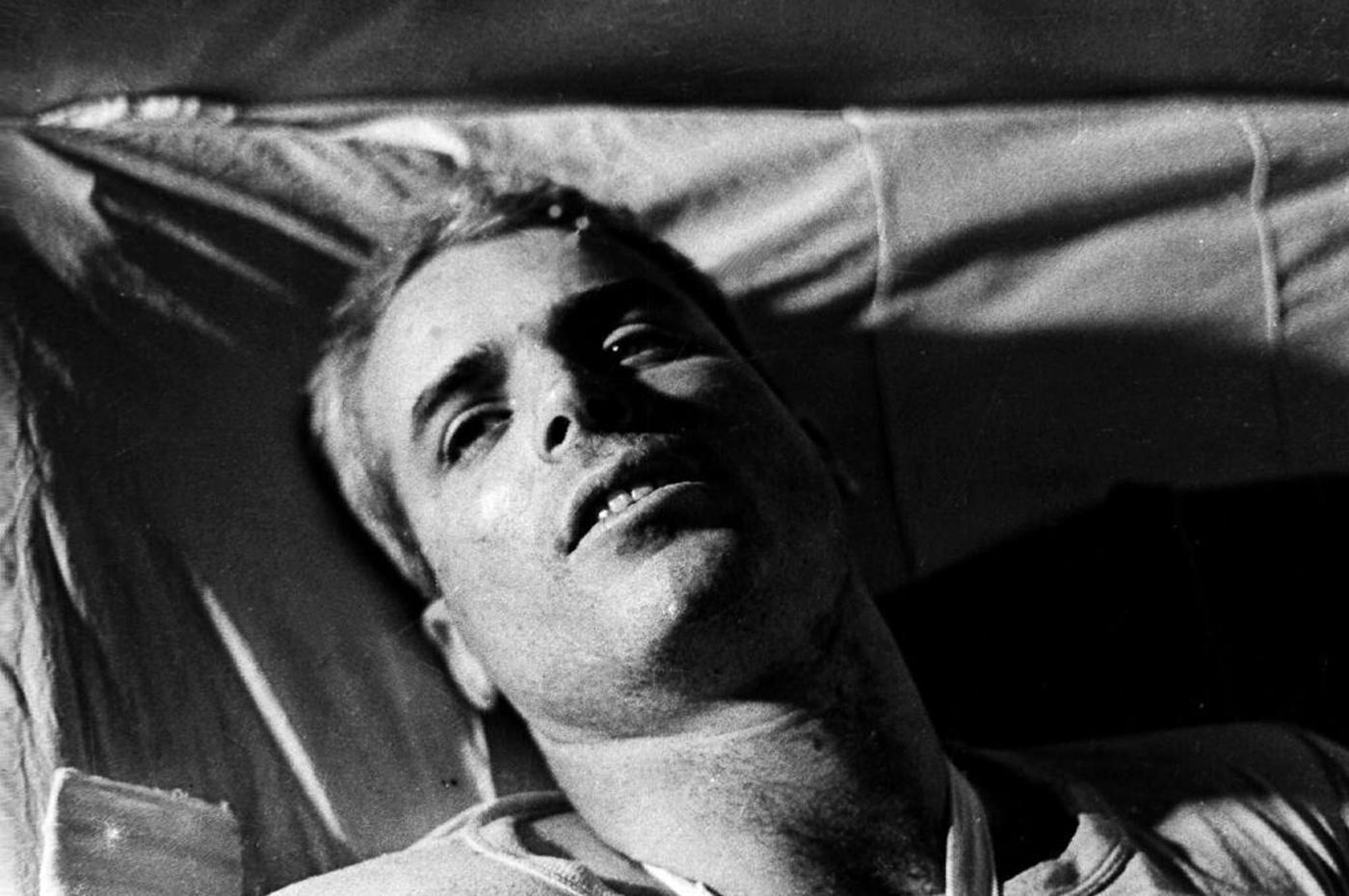

McCain’s captors tortured him in the hopes he would reveal military secrets. He was beaten unconscious repeatedly. Doctors refused him treatment for his broken bones or wounds, expecting death to take him at any time. Only when they realized McCain’s lineage did the North Vietnamese transport him to the hospital, where he picked up the mocking title “The Crown Prince.” When he recovered a bit, the beatings resumed. Propaganda video from this era showed him a gaunt, on-the-verge-of-death ghost.

As McCain’s captors considered his fate, they offered his release. McCain refused, citing U.S. policy that the prisoners who were taken earliest should be the first to be released. He spent another five years as a POW, during which time the cruel treatment continued.

Upon his release on March 14, 1973, McCain wanted to “get on with it,” a frequent phrase he used when confronting tough junctures. He underwent extensive physical therapy, studied the Vietnam War at the National War College and moved to Jacksonville, Fla., where he would command the Navy’s largest aviation squadron. During this time, his marriage began to falter, and McCain acknowledged infidelity. It was another symptom, Carol McCain said, of a man who was in his 40s trying to act 25.

McCain, who toyed with the idea of running for office in Florida, instead moved back to Washington as the Navy’s liaison in the Senate. In 1979, he met Cindy Hensley at a reception for senators in Hawaii. Hensley was an Arizona teacher 18 years his junior, the heiress to a beer distributorship, “as beautiful as she was rich,” one columnist would later write. McCain, who was still married at the time, started making regular trips to visit her in Phoenix. The couple married on May 17, 1980—six weeks after his divorce to Carol was finalized.

Less than a year later, Captain McCain shelved his stalled Navy career and retired with the intention of seeking elected office. With the backing of his new in-laws, who lived across the street to help with what would be four more children, including journalist Meghan McCain, he ran for a U.S. House seat in Arizona in 1982. Rivals attacked him as a carpetbagger. McCain defused the criticism masterfully: “The longest place I ever lived was Hanoi.”

After two terms in the House, McCain ran for the Senate and won, despite clashes with his party leaders, including President Ronald Reagan. But his dizzying political rise came dangerously close to ending in the late 1980s, when it was revealed McCain was among five lawmakers who pressured regulators to back off in their interest in a savings and loan institution based in California. A Senate ethics investigation said five lawmakers leaned over their skis on behalf of donor Charles Keating, but let the good-ol’-boys-system slide. About McCain, they said he exercised “poor judgment” but cleared him of ethical and legal wrongdoing.

McCain got off with a slap on the wrist, and turned his sights to reforming the campaign-finance system, a goal that, in characteristic fashion, put him at odds with GOP orthodoxy. Working across party lines, he partnered with Wisconsin Senator Russ Feingold, a progressive Democrat, on a plan that imposed new limits on soft-money spending. Bipartisan approaches to big intractable problems became a McCain hallmark, presaging his repeated and incomplete attempts to overhaul the nation’s immigration system and his more successful efforts, alongside Democratic Senator and fellow Vietnam veteran John Kerry, to lay the groundwork to normalize relations with Vietnam in the 1990s.

TWO PRESIDENTIAL RUNS

This independent streak was on full display as the nation prepared for the 2000 presidential race. Party brass and high-dollar donors coalesced behind Texas Gov. George W. Bush, the son of a former President who had shown what a reform-minded governor could accomplish in a deeply conservative state. McCain didn’t think Bush was the right recipe for the new millennium and mounted a strong insurgent challenge. Calculating that he could not compete in the campaign-opening Iowa caucuses due to his opposition to ethanol subsidies, he effectively moved to New Hampshire, where he punctured the frontrunner’s aura of inevitability, trouncing Bush by almost 20 points. For McCain’s supporters, it was a triumphant affirmation that money couldn’t assassinate ideas in politics.

McCain’s momentum came to an ugly halt a few weeks later, when South Carolina’s notoriously vicious Republican primary featured unfounded rumors that McCain had secretly fathered an African-American child. After one debate in Columbia, every car in the parking lot had a flier with the false charge stuck under the windshield wiper. The smears were against McCain’s daughter, Bridget, whom John and Cindy had adopted from Mother Theresa’s orphanage in Bangladesh in 1993. (The McCain campaign blamed the Bushes or their allies for the attacks. The Bush team denied it, but clearly benefited from it.) So spooked was McCain that he did a rare thing: punt on a question of principle. He begrudgingly told voters in South Carolina it was up to them whether the Confederate flag should continue to fly at the statehouse. After losing the state, he admitted he was wrong. “I feared that if I answered honestly, I could not win the South Carolina primary,” McCain said. “So I chose to compromise my principles. I broke my promise to always tell the truth.”

McCain’s campaign ended a few states later, and he finally endorsed Bush over Vice President Al Gore. But McCain would be a thorn in the side of the 43rd President. He bucked Bush on the question of torturing enemy combatants from the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, questioned the President’s management of the Pentagon and voted against Bush’s tax cuts, against his energy bill, against plans to cut taxes and pile up red ink.

Eight years after his first attempt, McCain decided once again to pursue the presidency. This time, he wanted to marry his maverick spirit to a Bush-caliber political machine. But his 2008 bid got off to a rough start. McCain was dogged by campaign dysfunction and his continued support for an increasingly unpopular war in Iraq. “He was the biggest proponent of the war in Iraq at a time when the popularity for the war in Iraq … collapsed,” says Rick Davis, McCain’s 2008 campaign manager who couldn’t talk his friend out of that position. Nor could they talk him into trashing Bush, whose approval numbers had cratered. “John McCain was never going to go out and say ‘George Bush stinks.’ That just wasn’t going to happen,” says Sarah Simmons, the campaign’s director of strategy.

Donors stopped giving. McCain had to lay off some of his most loyal staffers to comply the new campaign finance rules he wrote. Meanwhile, a candidate whose long, off-the-cuff conversations with journalists on his campaign bus had become legend proved to be unprepared for the immediacy of the first social media election. One free-flowing conversation about women’s health turned into a weeks-long story after an adviser drew the candidate into a sideshow debate about why some health plans covered Viagra for men but not contraception for women. The conversation spiraled out of control—perhaps costing that adviser, former Hewlett-Packard CEO Carly Fiorina, the VP slot on the McCain ticket. Conservatives were already shaky on McCain’s credentials, and McCain could not elevate someone openly urging contraception coverage.

Trailing Senator Barack Obama as the general election moved into the summer, McCain tried to spark a comeback with the roll of the dice. He picked first-term Alaska Gov. Sarah Palin as his vice presidential running mate. Palin gave the campaign a short-term jolt, but proved to be disastrously ill-prepared and poorly-vetted for the job. As Palin incensed campaign aides behind the scenes, crowds at her rallies turned angry against Obama and shouted racist language about him. It got so bad that McCain himself took away a woman’s microphone during a Friday night town hall event in Minnesota when she suggested the Illinois Senator was “an Arab.” McCain defended his opponent as a good man.

McCain’s handling of the economic meltdown also planted doubts in voters’ minds. In late September, just before the first presidential debate, the Republican abruptly announced that he was suspending his campaign to return to Washington to work on what many voters saw as a Wall Street bailout. But when he arrived at the White House for a bipartisan meeting with Bush, McCain came off as unprepared and had few contributions to make. Congressional Democrats, meanwhile, gave the floor to Obama to represent his party. Realizing he was out of his depth, McCain appeared at the debate the next day.

In the end, after spending more than $330 million, the 72-year-old McCain lost by 9.5 million popular votes. “After I lost I slept like a baby,” McCain would say frequently. “Sleep two hours wake up and cry. Sleep two hours wake up and cry.” He had already lived longer than his father and his grandfather, but had no interest in retirement, as some aides proposed. Once again, he forged ahead.

SAYING GOODBYE

In the Obama era, McCain refashioned himself as a frequent check against the Democratic President’s foreign policy. McCain fought to preserve the ban on gays and lesbians serving openly in the military and campaigned against an economic stimulus package. He continued to travel extensively, including a trip to Afghanistan and Pakistan with Sen. Elizabeth Warren, a Massachusetts Democrat, two weeks before he announced his diagnosis.

By then, McCain moved a little less quickly through the hallways in the Senate. His wit and humor, which made him famous, seemed a little duller. He was having less fun in the Senate, where a Palin-induced Tea Party wave came crashing against the marble gates of the Upper Chamber; he hated the uncompromising attitudes of newcomers like Ted Cruz, the Texas Senator whom McCain famously christened a “wacko bird.”

As Donald Trump’s campaign gained steam in 2016, McCain told friends he didn’t recognize his party that would admit newcomers like Trump. This was, after all, the party for whom Hillary Clinton campaigned as a “Goldwater Girl.” How was the thrice-married Trump its new leader? How had the party of Ronald Reagan, Bob Dole and even former rival Mitt Romney comes to be represented by the undisciplined New York billionaire?

The schism was mutual. “He’s not a war hero,” Trump said in 2015. “He was a war hero because he was captured. I like people who weren’t captured.” McCain never forgave him, and Trump never let up. Even in February 2018, as McCain struggled with cancer, the President told conservative activists that he was the reason why Obamacare remained on the books. When Trump signed a defense bill in August of 2018, named in honor of longtime Senate Armed Services Committee Chairman McCain, the President and his White House refused to mention the Senator by name.

By the summer of 2017, McCain’s poor health began to show. During questioning of former FBI Director James Comey at a Senate hearing, McCain held forth in ways that left friends and family worried. He called the dismissed FBI chief “President Comey” and appeared confused. The Senator released a statement making light of the uneven performance: “maybe going forward I shouldn’t stay up late watching the Diamondbacks night games.” But the diagnosis of glioblastoma arrived within weeks.

When it came time for McCain to release what would be his final book, a coda to his life in politics and some last reflections on the current climate, he was not well enough to promote it. That role fell to his longtime collaborator Mark Salter, and to a flattering HBO documentary about his life. McCain was determined to see the release of both.

In recent months, McCain has spent much of his days on his cell phone, calling friends and telling war stories. Former aides and dignitaries, including Vice President Joe Biden, stopped by the Arizona ranch for visits. Last fall, he summoned his campaign team from 2008 to a barbecue at longtime ally Rick Davis’ home in Northern Virginia. He wanted to see them again, to relive the days aboard the Straight Talk Express, even if it was clear to many that he was forgetting names and details. He had been through a difficult campaign—indeed, a difficult career—and emerged stronger for it. Even in defeat, he never let bitterness linger. As McCain liked to say, it could always get worse. It’s always darkest before it goes totally black.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Philip Elliott at philip.elliott@time.com