Infectious diseases know no borders. In this age of global hyper-connectedness, a disease outbreak anywhere is a threat everywhere. With just a sneeze, a hug or a plane ride, a deadly germ can travel from West Africa to North Texas before we even realize the threat exists.

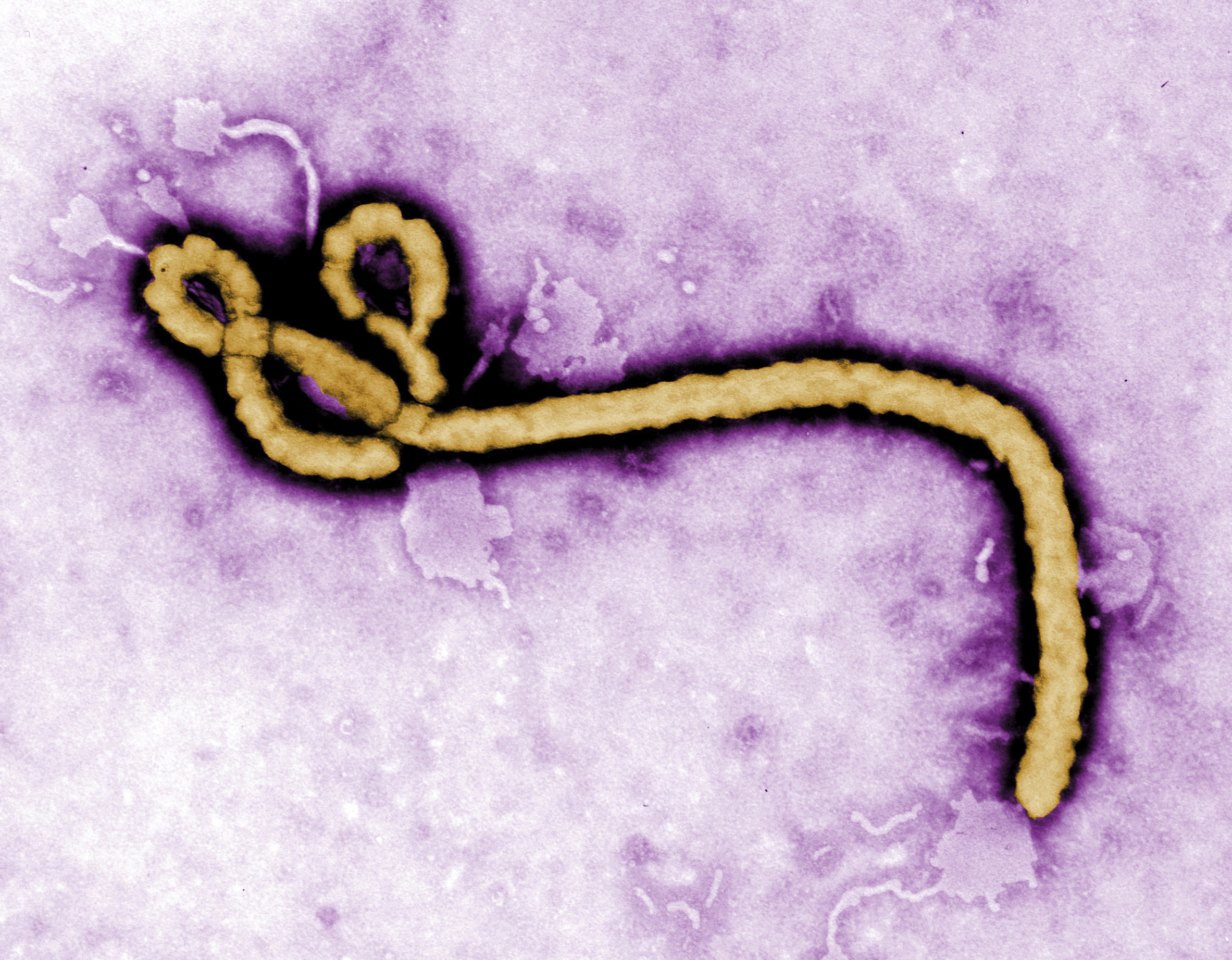

We learned this in 2014, with the Ebola crisis. While Ebola is fairly hard to catch, it left more than 11,000 people dead — and served as an enormous wake-up call. Republicans and Democrats in Congress put down their partisan swords. Senator Lamar Alexander (R-TN) told a crowded hearing room on Capitol Hill, “We must take the deadly, dangerous threat of the Ebola epidemic as seriously as we take ISIS.” And since that year, the U.S. has been a leader in the Global Health Security Agenda. America made these changes because it understood that epidemics affect everything — health, jobs, migration and war.

Unfortunately, we have a short memory.

The U.S. government is now perilously close to gutting smart and essential initiatives aimed at keeping disease outbreaks from spreading across the globe. The Centers for Disease Control told employees in January that, in anticipation of budget cuts of up to 80%, it will shutter much of its work helping mostly low-income, developing countries to strengthen their capacity to rapidly detect, prevent and control infectious disease outbreaks before they spread.

Experts say no other country is likely to pick up where we leave off. In 2016 alone, the CDC tracked 37 dangerous pathogens — like MERS, Zika and yellow fever — in more than 130 countries.

If this drawdown comes to pass — likely by October 2019 — a critical CDC division that focuses on global health protection will retreat from all but 10 of the 49 countries where it currently works. It will abandon fragile and under-resourced hot spots for emerging infectious diseases, including astonishingly enough Sierra Leone and Guinea — two of the three West African countries where Ebola raged in 2014 and 2015.

Prevention and early investments can make all the difference in saving lives both abroad and on our shores. While its neighbors saw skyrocketing numbers of Ebola patients, Nigeria recorded only 20 cases total. Earlier investments by America’s signature HIV and AIDS relief program, known as PEPFAR — now marking its 15th year — were central to helping build and strengthen the Nigerian health system enabling the country to be the first to successfully contain and eliminate the Ebola threat.

In spite of modern medical and public health advances, the world remains woefully unprepared to fend off a perfect, pathogenic storm. When Swine Flu swept the world in 2009, hundreds of thousands of people died during the first year the virus circulated. And 100 years ago, the Spanish Flu infected approximately 500 million people worldwide and killed close to 50 million. A new massive pandemic could take a staggering number of lives.

On top of the human toll, disease outbreaks can be hugely disruptive economically. The global economic impact of the 2003 SARS epidemic totaled approximately $40 billion, and according to the World Bank, a worldwide flu epidemic would reduce global wealth by $3 trillion. Even if the illness somehow never reaches the U.S., Americans will still feel it. According to a recent analysis of 2015 U.S. Department of Commerce data, U.S. exports to the 49 countries where the Global Health Security Agenda works exceed $308 billion and support more than 1.6 million jobs of all kinds, in all states. That is 13.7% of all U.S. export revenue worldwide and 14.3% of all U.S. jobs supported by U.S. exports.

Moreover, when epidemics bring countries to their knees, there’s also a high risk of unrest and chaos that can drive displacement across borders only breeding further instability. Desperation can explode and create a vacuum for extremism and others to step in. One only has to look to Yemen to see the nexus of how terrorism, famine and disease can compound to create incredible human suffering in ways that are immensely difficult to unravel.

Sadly, this is just one example of the impact of cuts to America’s international affairs programs. Last week, the Administration proposed a new cut of 30% to the State Department, USAID and other development agencies, including a 23% cut to global health programs. At a time of growing dangers threatening America — whether from ISIS, famines or pandemics — we cannot afford to pull back from the world.

As with our military, we cannot budget based on yesterday’s wars. Instead, we must be smart enough to recognize tomorrow’s threats. America’s investments to strengthen health systems in fragile states worldwide are far more than a humanitarian expression. Together, our development and diplomatic programs are an essential investment in our own national, economic and health security — and doing so requires planning, preparation and resources. Without it, we expose our citizens to grave risks. Next time, the sneeze on the other side of the world could be much more dangerous.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com